Out of the twenty writers named in my last post, here, in ascending order, are my top five choices for the 2011 Nobel Prize in Literature:

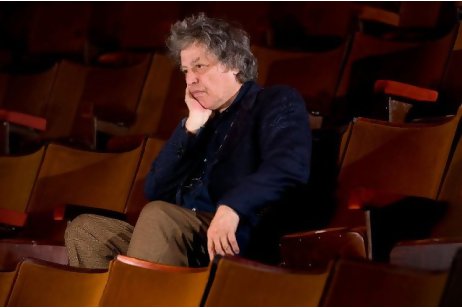

5. Tom Stoppard

5. Tom Stoppard

From Great Britain comes one of the world’s greatest living playwrights. His work is characterized by extreme erudition, almost miraculous wordplay, and tremendous philosophical and moral depth. Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, Rosencrantz and Gildenstern are Dead, and the epic The Coast of Utopia, are three of his most famous plays, but my personal favorite is The Invention of Love, about the poet A. E. Houseman, about his unspoken life-long love for a handsome young athlete, and by extension, about silences, the silence of lost classical texts, about the silence of what cannot be communicated through translation, both literal and figurative. Here is part of a monologue spoken by one of Houseman’s associates, Walter Pater, the great critic, essayist and scholar.

PATER: … The Renaissance teaches us that the book of knowledge is not to be learned by rote but is to be written anew in the ecstasy of living each moment for the moment’s sake. Success in life is to maintain this ecstasy, to burn always with this hard gem-like flame. Failure is to form habits. To burn with a gem-like flame is to capture the awareness of each moment; and for that moment only. To form habits is to be absent from those moments. How may we always be present for them? — to garner not the fruits of experience but experience itself?—

(At a distance, getting no closer, Jackson [the object of Houseman’s love] is seen as a runner running towards us.)

…to catch at the exquisite passion, the strange flower, or art – or the face of one’s friend? For, not to do so in our short day of frost and sun is to sleep before evening. The conventional morality which requires of us the sacrifice of any one of those moments has no real claim on us. The love of art for art’s sake seeks to nothing in return except the highest quality to the moments of your life, and simply for those moment’s sake.

JOWETT (Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol) Mr. Pater, can you spare a moment?

PATER: Certainly! As many as you like!

4. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

4. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

I learned about this astounding writer from Russia a couple of years ago through an article by Jane Smiley in the New York Times Book Review. She mentioned a book of stories called There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby: Scary Fairy Tales. It is, as the title would indicate, a collection like no other, a book of “nekyia” or “night journeys”, descents into the underworld, literal or social, in which one is never sure which reality is the more “real”. Last month, I read her short novel The Time: Night, published in the waning days of the Soviet Union, in which, through the voice of a woman on the edge, a poet trying to hold together her disintegrating family in one hand and her sanity in the other, she lays bare a desperation as harrowing as any I have read. In addition to being one of the most preeminent authors and playwrights in Russia, she is also a popular cabaret artist. May all good things come to this over-the-top genius. Here is the first paragraph of her story The Arm.

During the war, a colonel received a letter from his wife. She misses him very much, it said, and won’t he come visit because she’s worried she’ll die without having seen him. The colonel applied for leave right away, and as it happened that just a few days earlier he’d been awarded a medal, he was granted three days. He got a plane home, but just an hour before his arrival his wife died. He wept, buried his wife, and got on a train back to his base – and suddenly discovered he had lost his Party card. He dug through all his things, returned to the train station – all with great difficulty – but couldn’t find it. Finally he just went home. There he fell asleep and dreamed that he saw his wife, who said that his Party card was in her coffin – it had fallen out when the colonel bent over to kiss her during the funeral. In this dream his wife also told the colonel not to lift the veil from her face.

3. Alice Munro

3. Alice Munro

What this great Canadian dredges up from somewhere near the sewer system of her character’s souls, and how she does it – by sticking unflinchingly to the apparent surface of things – makes her, to my mind, an unqualified genius. Her metier may be the declasse short story, but she has so exploded that form, and in such an organic, un-showy way, that she sits comfortably along side any of the great innovators of fiction at work today. Then there is the service she does for her region, bringing Southwestern Ontario into international consciousness for the first time, as surely as Pearl Buck brought China to the West. Only, Munro has a far superior linguistic apparatus with which she does this. I don’t know anyone who packs so many layers of information into such short, unadorned sentences.

In this passage, from the story The Bear Came Over the Mountain, a man, Grant, unable to care for his wife, Fiona, who has Alzheimer’s disease, has put her a nursing home, where, forgetting their long happy marriage, she falls in love with a fellow patient, Aubrey. Aubrey’s wife has decided to remove her husband from the nursing home and care for him at home. Grant sees his wife’s suffering and takes action:

Then he took the plunge, going on to make the request he’d come to make. Could she consider taking Aubrey back to Meadowlake maybe just one day a week, for a visit? It was only a drive of a few miles, surely it wouldn’t prove too difficult. Or if she’d like to take the time off – Grant hadn’t thought of this before and was rather dismayed to hear himself suggest it – then he himself could take Aubrey out there, he wouldn’t mind at all. He was sure he could manage it. And she could use a break.

While he talked she moved her closed lips and her hidden tongue as if she was trying to identify a dubious flavor. She brought milk for his coffee, and a plate of ginger cookies.

“Homemade,” she said as she set the plate down. There was challenge rather than hospitality in her tone. She said nothing more until she had sat down, poured milk into her coffee and stirred it.

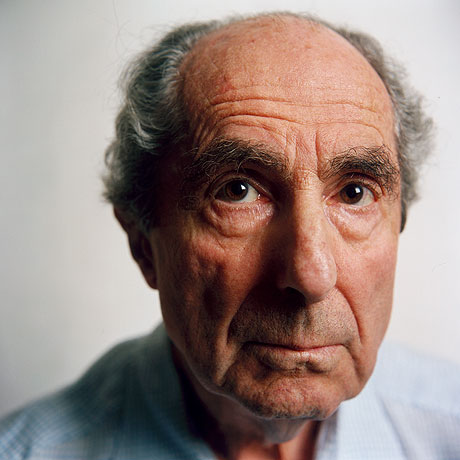

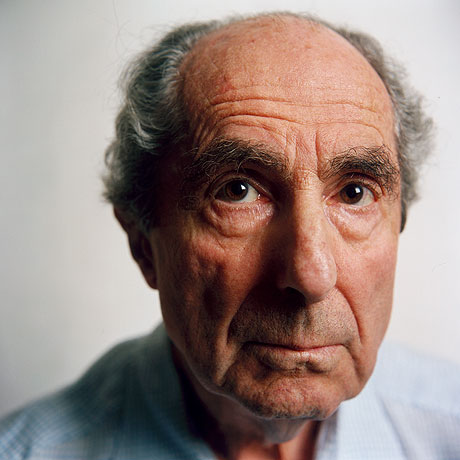

2. Philip Roth

2. Philip Roth

Yes. I know: Sex. Frantic masculinity. A little misogyny, anyone? Endless rants. But really, who in America writes like this? Sam and I frequently discuss him. Sam’s concern is that Roth belongs to the “sex-as-salvation” family of narcissistic straight white male writers. I contend that, to the contrary, his best work lays bare the sheer benightedness of such a theology. And not just sex, but all the signifiers of the “American Dream” – power, wealth, social acceptance – you name it, he gives the lie to it. Far from being adolescent in his sensibility, as he is often accused, he takes down our adolescent country in prose as energetic and beautiful as any being written. Here, from one of my favorite American novels, The Human Stain, is what I mean:

It was the summer in America when the nausea returned, when the joking didn’t stop, when the speculation and the theorizing and the hyperbole didn’t stop, when the moral obligation to explain to one’s children about adult life was abrogated in favor of maintaining in them every illusion about adult life, when the smallness of people was simply crushing, when some kind of demon had been unleashed in the nation and, on both sides, people wondered “Why are we so crazy?”, when men and women alike, upon awakening in the morning, discovering that during the night, in a state of sleep that transported them beyond envy or loathing, they had dreamed of the brazenness of Bill Clinton. I myself dreamed of a mammoth banner, draped dadaistically like a Christo wrapping from one end of the White House to the other and bearing a legend A HUMAN BEING LIVES HERE. It was the summer when – for the billionth time – the jumble, the mayhem, the mess proved itself more subtle than this one’s ideology and that one’s morality. It was the summer when a president’s penis was on everyone’s mind, and life, in all its shameless impurity, once again confounded America.

1. Tomas Tranströmer

1. Tomas Tranströmer

Here is an example to illustrate why, to my mind, there is no greater living poet than this man from Sweden.

TRACK

2 A.M.: moonlight. The train has stopped

out in a field. Far-off sparks of light from the town,

flickering coldly on the horizon.

As when a man goes so deep into his dream

he will never remember that he was there

when he returns to his room.

Or when a person goes so deep into a sickness

that his days all become some flickering sparks, a swarm,

feeble and cold on the horizon.

The train is entirely motionless.

2 o’clock: strong moonlight, few stars.

The award is scheduled to be announced this Thursday, October 6th. Until then, let the speculations fly. Who would it just make your week to see honored this year, and why?