I.

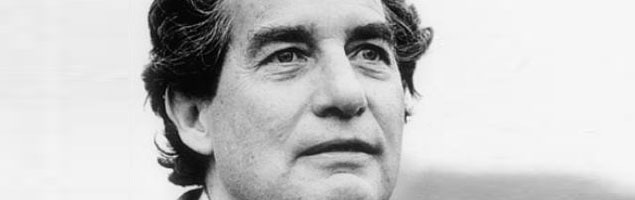

I try to imagine them meeting in Paris: the young Pär Lagerkvist and Gertrude Stein. He, a Swede of peasant stock, shock of blond hair, taciturn not even the word for his humming inwardness. She, agate-eyed, operatic in force and figure, Alice in tow, compelling him to come furrow his Nordic brow at the three Juan Gris paintings she’s just purchased. What an awakening it must have been for him – this woman, this modern art – comparable, perhaps, to his discovery of the work of Charles Darwin while at the gymnasium not so many years earlier. That prior awakening had precipitated, or at least correlated with, a radical turn from the pietistic religion of his parents to an ardent, agnostic socialism. He and a small group of likeminded students would meet on Sunday mornings, as the church bell tolled in the little town of Växjö, in southern Sweden, where he’d grown up, to discuss Thomas Huxley, Flammarion, and Kropotkin. In Paris, he sees, there would have been no need for such statement making. Paris. And this woman! These paintings!

I try to imagine them meeting in Paris: the young Pär Lagerkvist and Gertrude Stein. He, a Swede of peasant stock, shock of blond hair, taciturn not even the word for his humming inwardness. She, agate-eyed, operatic in force and figure, Alice in tow, compelling him to come furrow his Nordic brow at the three Juan Gris paintings she’s just purchased. What an awakening it must have been for him – this woman, this modern art – comparable, perhaps, to his discovery of the work of Charles Darwin while at the gymnasium not so many years earlier. That prior awakening had precipitated, or at least correlated with, a radical turn from the pietistic religion of his parents to an ardent, agnostic socialism. He and a small group of likeminded students would meet on Sunday mornings, as the church bell tolled in the little town of Växjö, in southern Sweden, where he’d grown up, to discuss Thomas Huxley, Flammarion, and Kropotkin. In Paris, he sees, there would have been no need for such statement making. Paris. And this woman! These paintings!

However I try, I can’t quite imagine this meeting, at least not without it coming off as a kind of mental cartoon in need of a caption. Stein, fundamentally large, the Empress of the avant guard, the quintessential American in Paris, seems formed of such different material from the bony young Scandinavian, practically born with intimations of mortality, looking like the mold from which any number of Bergman characters would later be cast. And yet, however unlikely, this meeting apparently happened, or so I read in the introduction to Evening Land, a volume of Lagerkvist’s late poems. I read that the art to which she exposed him – expressionism, cubism, naivism – influenced his early breakthrough in style far more than anything in literature.

However I try, I can’t quite imagine this meeting, at least not without it coming off as a kind of mental cartoon in need of a caption. Stein, fundamentally large, the Empress of the avant guard, the quintessential American in Paris, seems formed of such different material from the bony young Scandinavian, practically born with intimations of mortality, looking like the mold from which any number of Bergman characters would later be cast. And yet, however unlikely, this meeting apparently happened, or so I read in the introduction to Evening Land, a volume of Lagerkvist’s late poems. I read that the art to which she exposed him – expressionism, cubism, naivism – influenced his early breakthrough in style far more than anything in literature.

II.

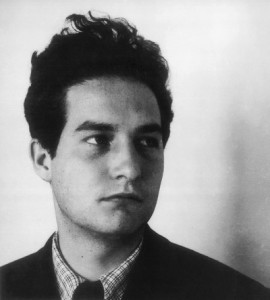

Pär Lagerkvist’s life seems to have been haunted by two enormities: God and Death. In his autobiographical novel, Guest of Reality, the principal character is a boy named Anders. Anders is born into a fiercely protestant family in which the Bible is one of the few books in the house. He becomes so obsessed with his fear of death that on a rainy day he takes himself to a flat stone in the forest to pray for the life of each member of his family. After a terrifying vision of a ghost locomotive rushing into the night in a spray of sparks, he comes to believe that the world of his father, in which all things were secure and certain under the certainty of God, was not real, and not his. Instead, “It just hurtled, blazing into the darkness that had no end.”

It would prove to be an irrevocable divide for Pär, this longing for God while watching the very idea of God recede beyond possibility.

If you believe in god and no god exists

then your belief is an even greater wonder

Then it is really something inconceivably great.

Why should a being lie down there in the darkness crying to

someone who does not exist?

Why should that be?

There is no one who hears when someone cries in the darkness.

But why does that cry exist?

Some of his very first writings were explorations of this divide. In 1912, before Paris, Stein, cubism, he wrote a piece for a Socialist magazine in which he envisioned a young hunter who catches sight of a woman by a spring. The hunter’s feelings are divided: He both yearns for her and wants to withdraw from her. He follows her, keeping himself hidden. When she reappears at the spring, he decides to kiss her, only to discover that, like Narcissus, he has kissed nothing but his own image in the water. He is completely alone. Lagerkvist called this Gudstanken: the idea of God.

The woman, the hunter, and the spring, would reappear four and a half decades later in his novel The Sybil. This time the story is told by the woman. She is the chosen mouthpiece of a mysterious and powerful god. On feast days, pilgrims arrive by the hundreds at the temple with requests for prophecy. She enters a drug-induced trance during which the voice of the god erupts from her in inchoate shrieks and groans, which the priests then interpret. It becomes evident to her that they interpret in such a way as will benefit themselves and the economy of the town. She becomes a prophetess without faith. One day, walking through the woods, she arrives at a spring. She finds there a beautiful young man. Instead of a hunter, he is a one-armed soldier, and this time they meet, and fall in love. Their love becomes a god in which she can believe. When she becomes pregnant, she is expelled from the temple and banished forever from the town. The soldier, who had ceased loving her after witnessing her orgiastic convulsions at the temple, is discovered dead in a nearby stream. The child she bears grows up to be helpless and mute, forever an infant. In the end, he too leaves her, vanishing into the snowy peaks. And so she looses, at the same time, both a god of power and a god of love, and is left with what, at best, could be called a god of absence, and at worst, malevolence. But the god she longs for —that god does not exist.

For Lagerkvist, this divide, this longing for a nonexistent god, would itself become a kind of faith, if one accepts Paul Tillich’s term for faith as ultimate concern. “I am a believer without a faith,” he wrote, “a religious atheist. I understand Gethsemane, but not the jubilation over the victory.” But his work would show that he did have a kind of faith, a faith in the longing itself, as indicated by that subtly ecstatic final question of his poem, “But why, does that cry exist?” The asking belies a love that it does.

For Lagerkvist, this divide, this longing for a nonexistent god, would itself become a kind of faith, if one accepts Paul Tillich’s term for faith as ultimate concern. “I am a believer without a faith,” he wrote, “a religious atheist. I understand Gethsemane, but not the jubilation over the victory.” But his work would show that he did have a kind of faith, a faith in the longing itself, as indicated by that subtly ecstatic final question of his poem, “But why, does that cry exist?” The asking belies a love that it does.

Recently, I re-read Barabbas, the novel by which, if by any, Lagerkvist is generally known to readers in English. It is his imagining of the life of the world’s most famous bailed criminal. Beginning with his uncomprehending witness of the crucifixion, it traces his journey, not to faith, but near it, and into the ultimate, inscrutable dark. I found myself perplexed by Lagerkvist’s simple, almost naive, approach to the writing of this tale, wondering how he achieved such formidable drama. I think it is because of his love for that cry. It is the cry of one divided. In Lagerkvist’s vision, Barabbas, the man who cannot believe, burns with the greatest passion of all for God, or an idea of God to sustain him. That he never finds it is, paradoxically, his final grace; what would he have become if he had become, at last, peaceful? His eventual death at the hands of the Romans would, in the end, have had no more significance than that of any of the assured believers around him. Instead, he pays, by choice, the ultimate price for a God in whom he longs to believe but doesn’t, with no one to hear his “cries in the darkness.”

III.

May my heart’s disquiet never vanish.

May I never be at peace.

May I never be reconciled to life, nor to death either.

May my path be unending, with death its unknowable goal.

Fascinated, I read in quick succession The Sybil and The Dwarf, and found in each, as in Barabbas, a captivating protagonist, each different from the others in every way, save for an un-ironic seriousness through which they engage their ironic worlds. Each longs for God, or a stand-in for God, and fails to find either.

Fascinated, I read in quick succession The Sybil and The Dwarf, and found in each, as in Barabbas, a captivating protagonist, each different from the others in every way, save for an un-ironic seriousness through which they engage their ironic worlds. Each longs for God, or a stand-in for God, and fails to find either.

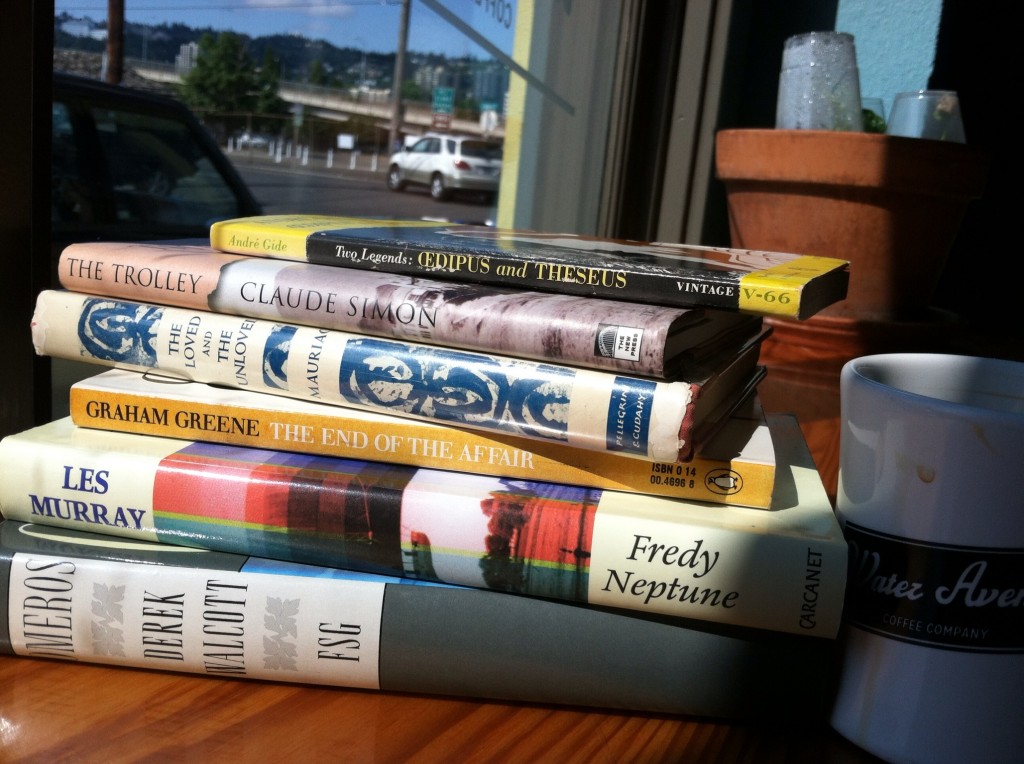

I wanted to know more. I had not known that Lagerkvist was a playwright, apparently a great one, considered the successor of Ibsen and Strindberg. Nor that he was one of a small handful of poets to bring Swedish poetry into the modern era. For a little over a week now I’ve had by my side Evening Land (Aftonland), his final collection of poems, published in 1953, and happily translated by W. H. Auden. I find in them a voice so potent I am amazed to have never come across his poetry before. He appears in none of my anthologies. Surely, he is no Tranströmer, lacking the later poet’s power of image and, what? levitation? But I now understand how Tranströmer would not have been Tranströmer without Lagerkvist.

One poem stopped me cold. It may be among the greatest statements of faith I have read by a modern poet:

I wanted to know

but was only allowed to ask,

I wanted light

but was only allowed to burn

I demanded the ineffable

but was only allowed to live.

I complained,

but nobody understood what I meant.

To ask. To burn. To live. This, in the end is all one is permitted. It is not, as it nearly sounds, an Eastern approach to enlightenment, for the payoff is patently not equanimity. The revelation here is that one must do these things with or without one to accompany.

IV.

I think that for Pär Lagerkvist, turning from God to Darwin, then to Picasso and Braque, was never really a turn from God in the first place, but rather a turning towards his own longing. I have no idea what kind of encounter he had with Gertrude Stein, or if there was any ensuing connection between them. But he must have seen in her another who, though she may never have said so, was, like him, longing for God. For what is the thirst for art and the far reaches of language if not a demand for the ineffable?