New Year. The usual sense of beginnings attends this time, and most of us who brought in the New Year on January 1st put forth a wish – even the hard-core rationalists among us who won’t continence the metaphysics of wishes – and that wish, silent or spoken, was that 2012 be a year of greater justice, reconciliation, and peace in the world. For a few of us, myself among them, it was our birthday.

To mark the new year, and to express my appreciation to you for stopping by my little corner of the web, and perhaps as a birthday present to myself, a stroking of my greedy curiosity, I’m extending an invitation to you, a chance to participate more directly in the on-going conversation about those wacky Nobel laureates. First, the invitation, and then something about what lies behind it:

I INVITE YOU TO SHARE WITH ME AND THE READERS AT THE SHELF A BOOK YOU HAVE READ BY ONE OF THE “FORGOTTEN” NOBEL LAUREATES.

You know the ones I mean. I’m talking about those names on the Nobel roster that make your brow furrow, many from the first two or three decades of the prize – Gerhardt Hauptmann, Theodor Mommsen, Grazia Deledda, for example – names that almost no one has heard of but that somehow, by chance or design, you have. Conversely, you can write about a little known, “forgotten” work by a more famous laureate. Has anyone looked into William Faulkner’s screenplays? You can write about a book you have read or a book that you hope to read. No high-falutin’ literary criticism necessary. Simply, tell us about your experience with the book: What did you think or feel about it? At what point in your life did you come across it? Did you finish it? Perhaps there is a body of work, like the epics of Henryk Sienkiewicz, that has always intrigued you, but that you haven’t yet found the time to read. Tell us why this obscure book or eclipsed author attracts you.

Send your reflections as a comment. You can leave it in the comments section found at the bottom left of any post on this blog. Share as much or as little personal information as you like. Unless you request otherwise, rather than publish what you send as a comment, I will make a post of it.

There is no time limit on this. You can share your reflections at any time throughout the year. I’ll be offering periodic reminders about this invitation. So, all you lovers of Maeterlinck, Eucken, Seifert, and Johnson, now is your chance. Don’t be shy!

The idea for this came to me on my birthday. One of Sam’s gifts to me was Fiasco, a novel, newly available in English, by the Hungarian Nobel Laureate Imre Kertesz. I’d been childishly giddy when I saw it, briefly, on the shelf at our local Barns & Noble. But, as so often happens with me, old sober-sides superego interposed and reminded me of the shelving crisis we have at home (really, its catastrophic) and of the backlog of books I have waiting to be read. Among the benefits of having someone in your life who knows you well and cares about you is that such a person is not bound by the dictates of your superego and can make things happen for you that you wouldn’t do for yourself. So. I now own Fiasco.

In spite of his having won the Nobel Prize relatively recently, in 2002, I know almost no one who has even heard of Kertesz. He is, apparently, another in the ever-expanding gathering of authors celebrated abroad whose course down American literary back roads kicks up barely a puff of dust.

I was reminded on New Year’s Eve of the shadowy charisma of the forgotten laureate. While friends and acquaintances were making plans for fireworks and inebriation, I decided to address the problem of the shelf of books in the bedroom, which is there at all because of the shelving crisis in our basement. Books, cascades of them, had long orflowed the adjacent foot area, and New Year’s being that time of new beginnings and all, it seemed the perfect moment to do a little rearranging (really, I can be a lot of fun, given suitable conditions). What I had thought would be a simple matter of taking the books off the shelf, moving it to a more auspicious wall, and returning them to the shelf, turned out to be more complicated than that: If I was going to take this much trouble, then I should do it right and assess which books I really wanted on this shelf, which could be sent down to the beleaguered basement shelves, and which could be boxed for storage or relocation.

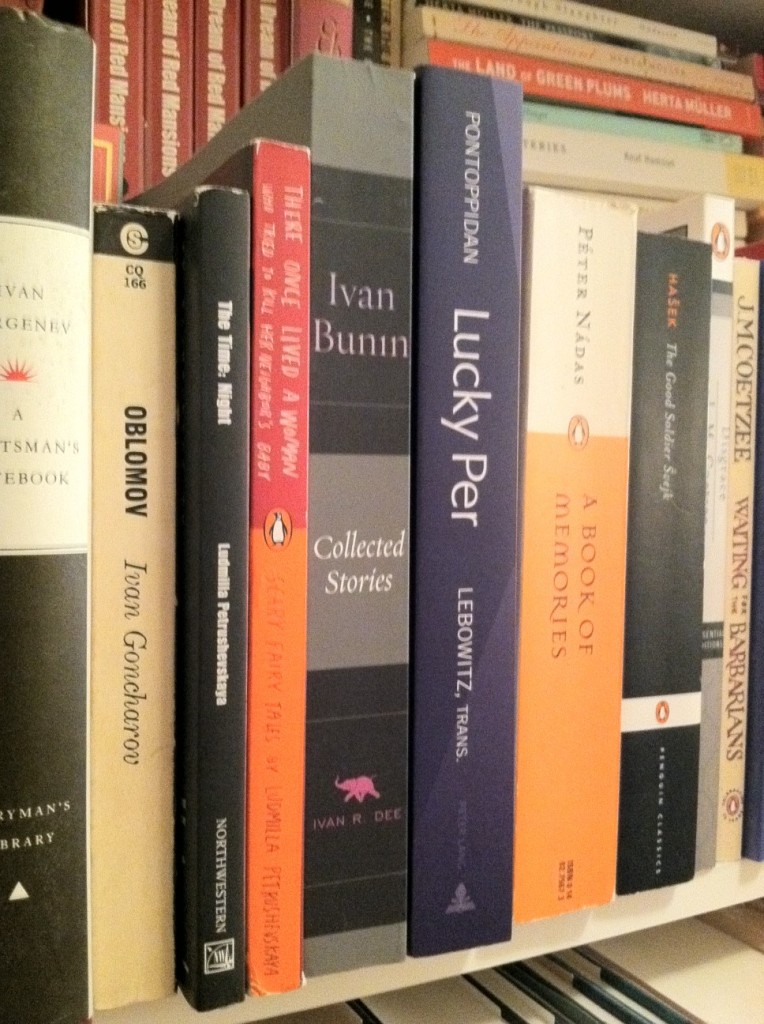

Among the nearly two hundred books I pulled off the shelf and stacked in crappy little piles around the room were many by Nobel laureates, Müller, Lessing, Pasternack, Gordimer, Grass, and Pamuk being among the more familiar names. Also on the shelf were several titles by one of my favorite authors, François Mauriac, a very great French novelist whose renown seems not to have cleared the shadow cast by the existentialists who followed him. But two books struck me as particularly… what?… esoteric? One is by an author I know, and one by an author I intend to read sometime this year. The first is The Collected Stories of Ivan Bunin. This nearly forgotten Russian emigre, the first Russian to win a Nobel for literature, is the author of one of my all-time favorite stories, “The Gentleman from San Francisco”. The second, Lucky Per, is the most famous novel by Henrik Pontoppidan, the Dane who won in 1917, and one of the most floridly obscure laureates on the list. Lauded by Thomas Mann, this work was only translated into English in 2010. I remember that when it arrived in the mail the thought occurred to me that I could be – really, its not impossible – that I was the only person in Denver to own this book.

Among the nearly two hundred books I pulled off the shelf and stacked in crappy little piles around the room were many by Nobel laureates, Müller, Lessing, Pasternack, Gordimer, Grass, and Pamuk being among the more familiar names. Also on the shelf were several titles by one of my favorite authors, François Mauriac, a very great French novelist whose renown seems not to have cleared the shadow cast by the existentialists who followed him. But two books struck me as particularly… what?… esoteric? One is by an author I know, and one by an author I intend to read sometime this year. The first is The Collected Stories of Ivan Bunin. This nearly forgotten Russian emigre, the first Russian to win a Nobel for literature, is the author of one of my all-time favorite stories, “The Gentleman from San Francisco”. The second, Lucky Per, is the most famous novel by Henrik Pontoppidan, the Dane who won in 1917, and one of the most floridly obscure laureates on the list. Lauded by Thomas Mann, this work was only translated into English in 2010. I remember that when it arrived in the mail the thought occurred to me that I could be – really, its not impossible – that I was the only person in Denver to own this book.

For those of us in thrall to such fetishes, the pleasure we derive from them is complex. There is the romance of discovery, the feeling of kinship with Hiram Bingham when he pulled back the Andean foliage and goggled at Macchu Picchu for the first time. “You mean, that’s been here all along?” Like all ploys for elite status, this one has about it the usual hedge against death, the feeling that knowing who Miguel Angel Asturias is, and even having read several of his books, somehow gives one special dispensation. Our immortality project is compounded when we project onto our discoveries and our heads whisper to themselves something like this: “If I’ve just come across Henrik Pontoppidan, so long languishing in the Hades of literary reputation, and through this discovery have in some way called him back to the upper world, then its not impossible that I, too, will be remembered, resurrected.

As I placed these books back on the shelf it struck me that there must be others who derive the same pleasure, and that these people, like me, must also derive the corollary pleasure of running across other readers who share their fondness for the forgotten. Hence, my invitation. I can’t wait to hear from you!

In the words of the late David Foster Wallace, “I wish you way more than luck” in the new year.