The American composer and voluminous diarist, Ned Rorem, made the following entry in his Nantucket Diary, dated 17 October, 1985:

The American composer and voluminous diarist, Ned Rorem, made the following entry in his Nantucket Diary, dated 17 October, 1985:

“When it comes to prizes there is no right choice, although with hindsight every choice can seem inevitable. Most witnesses are uncomfortable, especially the losers, and even the Nobel Prize is a raffle. In honoring Claude Simon the Nobelists now show themselves to admire the trend of form over content which has been festering in all French art for three decades, and which at its most extreme becomes the very definition of decadence. It makes me sad. If they had to choose a Frenchman, why not Simenon?”

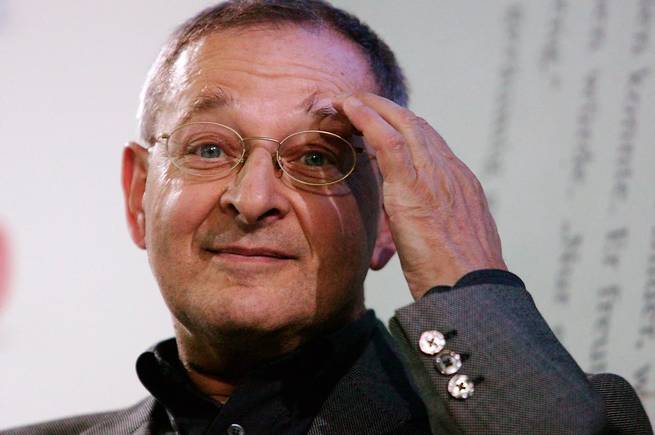

In the previous entry Rorem recounts a discussion with a friend about the pleasures of the prolific Georges Simenon, known for his hugely popular detective novels. Positing Simenon (who, for the record, was Belgian) as a Nobel contender is clearly intended to be cute. Simple fun, perhaps, with the closeness of the names. But Rorem’s real subject here is the commonplace that institutions which bestow awards have biases which can make their choices perplexing to those who don’t share them. The Nobel Committee has been coy about a wide range of them over its 113 years. Certainly this year’s award, to Patrick Modiano, another Frenchman, raises again this by now rather tired problem which, any more, is good for an easy, if not terribly interesting, diary entry. But when Rorem blithely tosses an author like Claude Simon onto the apparent trash heap of the whole post-World War Two French artistic enterprise, it smacks of posing.

First of all, I’m not exactly sure who he’s lumping Simon with. Perhaps he had in mind the painter Yves Klein, who instructed beautiful nude women to cover themselves in blue paint and roll around on his canvases. As a composer, he could be thinking of Pierre Boulez whose Le marteau sans maître (The hammer without a master) pits hyper-serialization against improvisation, at the expense of the uninitiated listener. Writer and mathematician Raymond Queneau, founder of the influential literary movement Oulipo, and Modiano’s acknowledged mentor, was at work in “all of French art” at the time; his Exercices de Style tells one story – a man runs into a stranger twice on the same day – in 99 different ways. And then there is cinema. The Nouvelle Vague. Really, Mr. Rorem?

No one could argue that form wasn’t a primary concern for these French artists. But, on that account, to dismiss them and their work out of hand, and a rather high one at that, is careless. It ignores the water in which these fish were swimming. In a world new to the idea of total annihilation by human initiative, a world forever to be haunted by Auschwitz, and a country which, “for the sake of form”, had been cravenly complicit with real and evident evil, and which, as if in response to its own shame, was narcotizing on the vestiges of empire (Algeria), a broken capitalism, and an increasingly indulgent consumerism, form was of the essence. As the students of May, 1968, knew, the forms were broken. Fervid formal experimentation, far from being a sign of decay, was the only morally viable artistic response. Form was the content. To a certain extent, it always had been, but never before had this been so widely understood. Unless it be, perhaps, in the Soviet Union of the 1930’s, in which case Mr. Rorem might wish to be mindful of which side of the argument he pursues.

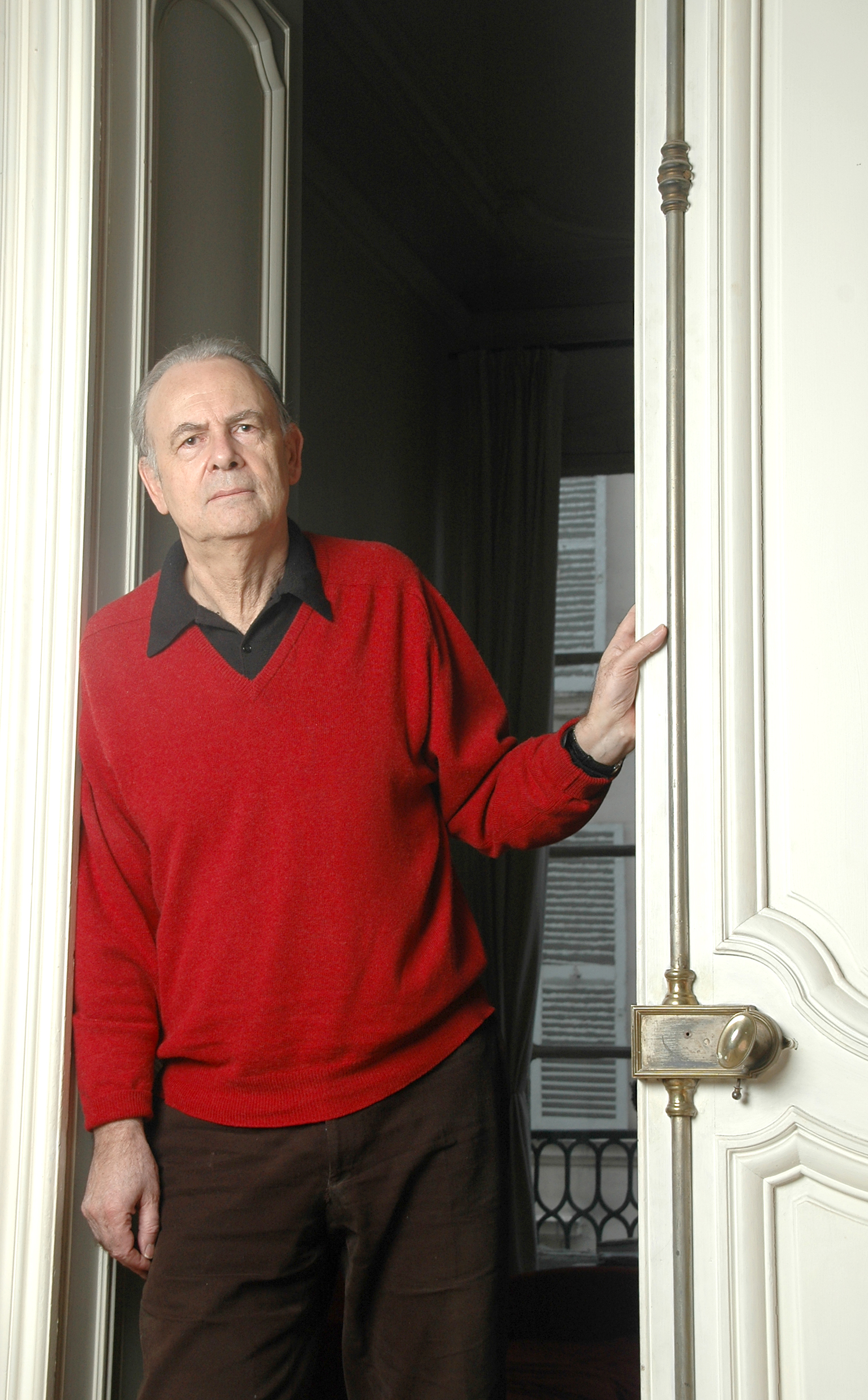

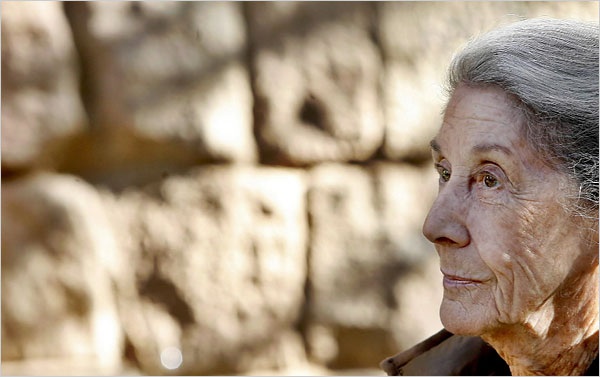

If formal experimentation in art were a crime, Claude Simon would certainly have been charged, convicted and sentenced. He is usually associated with a group of French novelists writing in the decades after the Second World War known as the nouveaux romanciers. Alain Robbe-Grillet, Natalie Sarraute, and especially Margurite Duras are more familiar names to readers in English, even though Simon was the only one of this loose fellowship to garner a Nobel. There are more differences than similarities among them, but they shared the common cause of attempting to transcend the received nineteenth century parameters of fiction, such as the centrality of plot, setting, character, and motivation. As with Boulez’s music, their books can seem difficult to the uninitiated. At its best, their writing can be starkly, startlingly beautiful, if, unavoidably, cerebral.

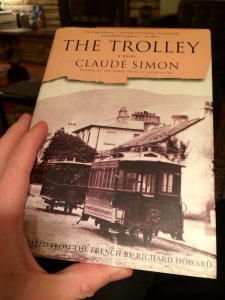

Claude Simon’s gorgeous final novel, The Trolley (2001), published when he was eighty eight, is all of these, and something more —it is haunting. To open this book is to find time splintering. On one page we read the impressions, or memories of impressions, of a young boy growing up in a coastal town in France, just after the First World War. On the next, an old man, presumably the same boy now in a stare-down with the end of his life, gives a somber, almost hallucinatory account of time spent in a modern hospital. A beginning and an ending, between which yawns an immense lacuna —the life lived. The novel is slim, where we feel it should, by rights, be long.

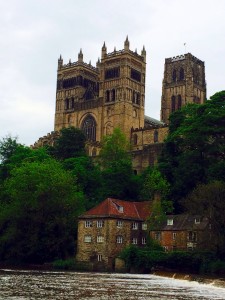

To speak of its form: The Trolley belongs to a sub-species of novel which doesn’t seem to be a novel at all. Memoir, meditation, travelogue, history, essay — these can seem more apt designations. It is in good company. W. G. Sebald, for example, in The Rings of Saturn, his grand investigation of entropy and loss, casts a wide net, gathering into his narrative hull the writings of the 17th century doctor Thomas Browne, the silk worms of the Chinese imperial court, and the personal lives of historical figures such as Roger Casement and Charles Algernon Swindburne. The narrator seems to be the author himself, and what he shares of himself has the ring of of autobiography. The photographs, grainy, melancholy, distributed throughout the pages contribute to the impression of a documentary, rather than fictive reality. But this itself is it’s fiction. J. M. Coetzee’s Summer Time is written as a biography of a writer named John Coetzee, whose salient distinction from the author himself is that he is deceased. Among the strangest and most brilliant recent examples of this kind of un-novel is Australian novelist Gerald Murnane’s Barley Patch, in which a subtle and poignant portrait of the artist emerges from a close examination of the unwritten lives of characters from his life in reading, and even from his own books.

In The Trolley, objects, scenes, episodes, and characters are observed, often at dauntingly close range, but are never manipulated through a plot. Which is not to say there is no story, but it is a story the reader constructs. For example, we are shown a garden with an iris border. It is an old, established garden with full-grown trees. It belongs to the narrator’s aunt and uncle on his father’s side, the family to whom he and his mother came after his father was, we infer, killed in the War. We are shown his mother lying on a chaise longue in this garden. She is sick. Later, we are shown the same garden, the same chaise longue, minus his mother. No plot here, but, most assuredly, a story. Even a cursory perusal of Claude Simon’s biography makes it apparent that this story is, or in every important way seems to be, his own.

Contrary to Simon’s reputation as a “difficult” writer, the writing here is not difficult. True, one has need of a healthy attention span to track with his immense, drifting sentences, but the language with which he fills these sentences attains a luminous, sometimes distressing, clarity. For example, we might almost wish for a filter through which to read his memory of the dour maid who tended his dying mother:

That same long Erinye’s face permanently stamped with an expression of outrage which she seemed never to leave off, whether caring for Maman with a sort of fierce tenderness or (suddenly appearing in the dim kitchen, leaning over the flickering glow of the flames) contemplating the torments of those rats she was burning alive (which, reported by the children, was strictly forbidden — despite which (but without witnesses) she doubtless continued doing), or again, still outraged and inflexible for all our pleading and tears, killing one after the other the kittens of her cat’s incessant litters, flinging them violently against the courtyard wall, picking up the tiny sticky balls of bloody hair if they still moved, flinging them against the wall again and then dumping them on the compost heap out of a basket which she then rinsed several times until there was no trace of blood left in it.

For all the violence here, it is that rinsing of the basket that most horrifies. Her tidying up, washing away all traces of the act, renders banal the preceding brutality, something brutality should never be. And it has the added effect of making this intimate horror echo against the great monuments of horror rising from a horrific century.

It is this kind of detail, banal on the surface, with which the book abounds. The novel’s opening paragraph, for example, begins with a close observation of the streetcar which the narrator road, as a boy, between school and the seaside community of tawdry mansions where his aunt and uncle lived. So close is this observation, in fact, that what we actually see first, without knowing quite what we’re looking at, is the dial in the streetcar’s cab. The “lens” pulls back to reveal the accelerator lever to which the needle corresponds, then further to encompass, not the hand, but the palm of the hand of the conductor managing the lever. Toward the end of the paragraph we are told that most of the varnish has worn off the handle of this lever, leaving the wood unprotected, and we begin to wonder how long this can go on. In the hands of a lesser writer, such grinding accumulation could quickly sink to indulgence. But the effect here is more akin to looking through a kind of personal Hubble telescope, not into the knowable universe, but the author’s own “deep field”. The image of the galaxies in that now famous dime-sized patch of sky confronts us with the sober knowledge that what we can directly experience of the universe approaches a statistical zero, and even that zero is revoked at death. This is the sensibility with which Simon presents the streetcar lever and its varnishless handle. “This existed”, he’s telling us – his urgency shimmers – as if trying to make a record of everything, knowing that, even late in his ninth decade, “everything” won’t, finally, be very much.

Death is a constant in this book, the rats and kittens being a stand-in for death on a larger scale, rarely seen but always in the offing. His father’s death precedes the narrative, and, though barely mentioned, is generative of all that follows. There are the physically and psychically decimated survivors of the War who, besides aimlessly pedaling go-carts around a stone monument at the town center, intensify the loss of those, perhaps luckier, who, like Simon’s father, didn’t survive. His mother’s death, alluded to rather than recounted, changes everything again.

But it is his proximity to his own death that provides the most salient structural element in the novel. The perpetual incursion of one time frame into another is a characteristic feature in all of Simon’s writing. In this case, his hospitalization late in life continually interrupts the narrative of his childhood. These incursions make up for what drama is lost by his eschewal of the more traditional buildup of tension through plot. For example, a memory from his boyhood, in which he is running to catch the trolley after school, follows on the heals of an episode in the modern emergency room to which he has been transported by ambulance, “a sort of coffin”; so when we see him breathlessly watching the missed trolley disappear around a corner, we already know that, in something like seven decades, there will be one very important ride he will not miss, and both scenes acquire a luminosity they would not otherwise achieve, and the metaphor of the trolley, carrying its passengers across the length of its finite line, comes into its own without ever a moment of underlining. The weight of this slim book owes, not to novelistic expansiveness, but to this kind of juxtaposition.

Another of Simon’s favorite techniques is the recurring image. In The Flander’s Road it is the half buried carcass of a horse. In The Grass it is a T of light cast through half-closed shutters onto an interior wall of a dying woman’s room. In The Trolley it is a woman on a hospital bed whom the narrator glimpses lying in the room opposite his. These images often hold a paradox. The horse, for example, is in an advanced stage of decomposition and buried in mud in spite of the fact that it can only have been dead about three, completely rainless, days. The paradox presented by the hospitalized woman is that her thick, well-kept blond hair, rosy complexion, and comparative youth don’t square with her lifeless, mask-like face. Not one to look for meaning, the narrator must, nonetheless, look for something, and so he looks for parallels. In her final appearance, she is on a bed designed to transport patients being wheeled away by two male nurses while the other patients on the ward look on. He sees in this somber procession a parallel to the parading of a saint’s effigy on a litter during a religious holiday. Then, at more length, he recalls witnessing a funeral procession in Benares, in which the cadaver, laid out on a litter, was borne, above a crowd of mourners, on the shoulders of two muscular men to the banks of the Ganges to be burned. He makes these parallels more or less explicit simply by their proximity to the image of the blond woman. More subtle is the parallel to his own mother’s face as she lies, slowly dying, on the chaise longue in his aunt and uncle’s garden. The two images, which never touch within the pages of the novel, call to each other, drawing the novel’s two dominant time frames into association. They orbit one another.

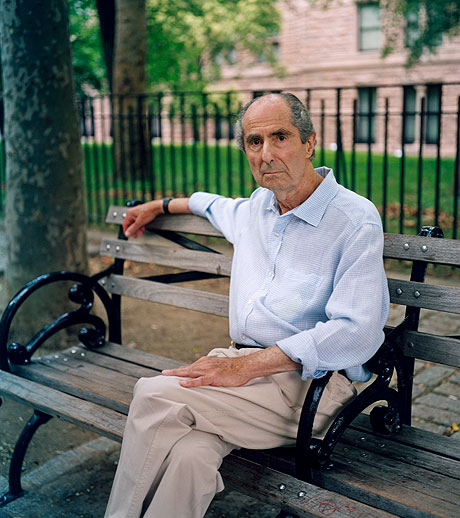

Reading The Trolley, one is aware of reading, not so much a novel, as an approach to the novel. This, in Rorem’s view, is what makes Simon, or artists like him, decadent. He clearly has in mind the word’s common implication of moral decline. But, as an aesthetic, all it really means is a preference for artifice over nature. In other words, the artist is happy to let you know he or she is up to something. There is a widespread, righteous criticism that praises the “artless”, the work in which the artist brilliantly hides or disguises all his scaffolding, so that the one receiving the work forgets that he or she is in the presence of a work of art at all. There are many pleasures in this approach. Marilynne Robinson writes like this, never calling attention to the weapon with which she quietly slays her readers. But there are equally great pleasures in the works of artists who want you to know that what they are making is art. Imagine a crestfallen Virginia Woolf whose readers never recognized that To The Lighthouse had significantly extended the reach of the form. I remember, as a twenty-year-old, reading Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, then saying to a friend, my age but wiser, “But people don’t really talk like that to one another.” To which he replied, “But, perhaps they should.”

Simon’s artifice laid bare the artifice readers had been accepting, unchallenged, for more than a century (Simon himself pointed out that such readers had apparently missed Proust, Joyce, and Faulkner). In The Trolley, the shifting time frames, the fragmentary presentation of memories and impressions, the protracted sentences, all make off with the reader’s habitual question, “what happens next?”. With causality out of the picture, the reader is invited to consider how else the presented elements of the narrator’s life might be related. This amounts to a deeper way of reading. One pauses at the spaces where, like in poetry, the frisson happens. This is not a matter of form over content. It’s a different kind of content.