I.

Every year the same: Christmas drops like a meteor into our little buckets of banality, displacing whatever has been disconsolate, complacent, poor, bored, boorish or small about our lives. We raise either a cheer or a howl, depending, or, perhaps if we are honest, one of each. Protest is vain – we’ve had ample warning. The Advent season, at least in the United States, long ago burst its liturgical boundaries, so that now we say, “Christmas music is playing in the stores, decorations are on display… Halloween must me coming.” The crassness of it all, its pervasiveness, is one of the ways we attempt to restore a bit of that displaced banality. That is to say, it is one of the ways we try to manage the holy, or the idea of the holy. Because if we simply let Christmas arrive, unmitigated by Rudolph, Santa, or charge cards – and we’re talking here about the essence of Christmas, quite apart from its Christian specifics, as the birth of That which can Save Us – if we simply let it blaze its tail through our atmosphere and land in our little buckets, then, first of all, there would be nothing left of our buckets. Then what? An end to all our tyrannies, little and large, by which we know our selves. Mostly we won’t have it.

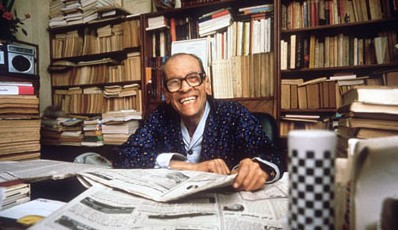

Twenty years ago today, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as leader of the Soviet Union and handed up a defunct superpower for history’s dissection. Twenty years before that, Joseph Brodsky, living in a monolithic Soviet Union that seemed to be going nowhere any time soon, having suffered Soviet cultural and intellectual tyranny, convicted as a “social parasite”, imprisoned in a mental institution, and about to be forced into exile, wrote: “Herod reigns but the stronger he is,/the more sure, the more certain the wonder./In the constancy of this relation/is the basic mechanics of Christmas.”

Herod reigns, to be sure. Herod reigns in Russia still, in Syria, North Korea. Herod reigns, too – let’s be honest about this – in all our hearts. But Brodsky says “the wonder” will out. That is how it works.

II.

Christmas morning: Soon the house will smell of the day-long meal. Sam, who has not been feeling at all well lately, rallied his energy to make a rustic pork terrine and, because our friend Nathan, a vegetarian, will be joining us, a terrine of roasted vegetables and goat cheese custard. These we will eat with crudité and Prosecco. For dinner, I’ve planned a spiced squash, fennel, and pear soup to be eaten with crusty bread, followed by a salad of asparagus, leeks, new potatoes and artichoke hearts with a tomato and hard-boiled egg vinaigrette. Then, coq au Riesling, garnished with chanterelle mushrooms and glazed baby red onions and served with little corn pancakes. Nathan will eat the corn pancakes with a stir-fry of red, green, yellow bell peppers with red wine vinegar. For dessert, we will have a chocolate polenta pudding cake.

Books, as always, will play a staring role in our gift exchange. I’ve bought Sam, among other titles, a book called Verdi’s Shakespeare, by Garry Wills. Sam is a besotted idolator of both these men, so when I read a review for this book in the New York Times a few weeks ago, I wondered, for one irrational moment, how Gary had gotten to know my partner so well without my finding out about it. Our friend Mary Louise, who loves to know a little bit about a lot of things, will be receiving E. H. Gombrich’s A Little History of the World. Sam bought the new Stephen King novel, 11/22/63, for our friend Keith. If I’m not mistaken, it will be the first time a Stephen King novel has appeared under a Christmas tree I’ve helped decorate. I can’t wait to see Nathan’s face when he opens The Adventures and Misadventures of Maqroll, by the Colombian novelist Alvero Mutis. Along with Sam, he is the most passionate reader I know, and he has a special affection for Latin American novels, especially the ones hardly anyone has heard of. And for me? I’ll let you know.

Sam is a passionate poetry lover. At some point during the day, he will insist we read poems aloud. One of them will be this one, by Joseph Brodsky:

DECEMBER 24, 1971

When it’s Christmas we’re all of us magi.

At the grocers’ all slipping and pushing.

Where a tin of halvah, coffee-flavored,

is the cause of a human assault-wave

by a crowd heavy-laden with parcels:

each one his own king, his own camel.

Nylon bags, carrier bags, paper cones,

caps and neckties all twisted up sideways.

Reek of vodka and resin and cod,

orange mandarins, cinnamon, apples.

Floods of faces, no sign of a pathway

toward Bethlehem, shut off by blizzard.

And the bearers of moderate gifts

leap on buses and jam all the doorways,

disappear into courtyards that gape,

though they know that there’s nothing inside there:

not a beast, not a crib, nor yet her,

round whose head gleams a nimbus of gold.

Emptiness. But the mere thought of that

brings forth lights as if out of nowhere.

Herod reigns but the stronger he is,

the more sure, the more certain the wonder.

In the constancy of this relation

is the basic mechanics of Christmas.

That’s what they celebrate everywhere,

for its coming push tables together.

No demand for a star for a while,

but a sort of good will touched with grace

can be seen in all men from afar,

and the shepherds have kindled their fires.

Snow is falling: not smoking but sounding

chimney pots on the roof, every face like a stain.

Herod drinks. Every wife hides her child.

He who comes is a mystery: features

are not known beforehand, men’s hearts may

not be quick to distinguish the stranger.

But when drafts through the doorway disperse

the thick mist of the hours of darkness

and a shape in a shawl stands revealed,

both a newborn and Spirit that’s Holy

in your self you discover; you stare

skyward, and it’s right there:

a star.