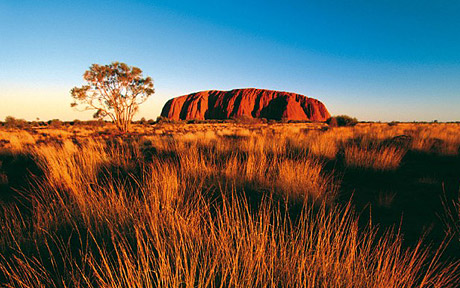

208 miles southwest of Alice Springs, in Australia’s Northern Territory, somewhat to the west and south of the dead center of the continent, where, were it a body, its heart would beat forth a circulation of scorching rocks and pebbles, rises Uluru, the sandstone monolith called Ayers Rock. Its 1142 vertical feet and 5.8 mile circumference have been home to the creator gods of the Anangu people for so far back in time as to yield time’s immateriality. Those who bandy the notion of history call its painted caves prehistoric. For those to whom it remains sacred, the only temporal frame with which to regard it at all it is the dreamtime. One legend has it that the Rock was originally an ocean on whose shores a great battle was fought. In protest, the earth itself rose up, and has remained. This accounts for the known parts. Its unknown parts extend, by some estimates, as much as 20,000 feet below the gibbers plain.

Uluru/Ayers Rock is the most recognizable image of the antipodean world, outstripping Sydney’s opera house, the fjords of New Zealand, and koala bears. The Cyclopean feature on the face of the desert defining the Australian interior. The people of Australia – not the People of the dreamtime, but the immigrants, descendents of European settlers and British penal colony overseers, those who, in the words of Patrick White’s Voss, “huddle” along the coast – live out their time either turning from or turning toward this 529,000 square miles of emptiness glaring out from the heart of the continent.

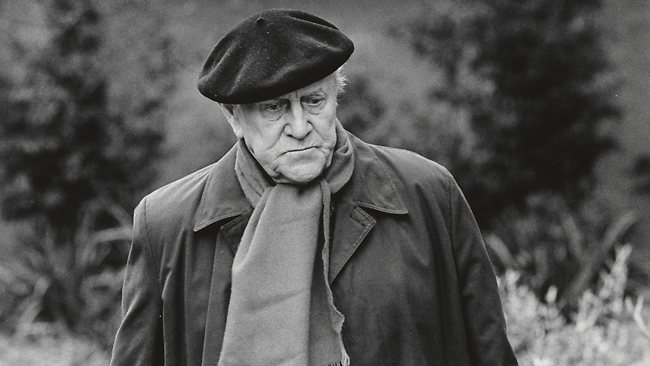

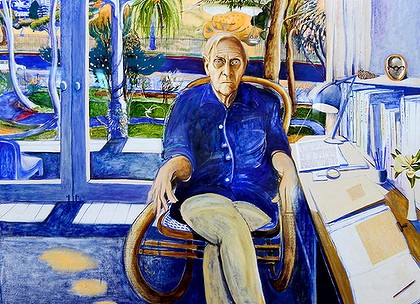

Patrick White was one who turned toward. His fiction rises, forbidding, beautiful, from the desert we all must cross who would count ourselves among the Living. As much as any writer of the twentieth century, he knew that the great expanse of emptiness must be explored, for emptiness is not nothingness but the only place from which we can know ourselves. And death, in the desert or the suburbs, is not life’s greatest peril. This distinction goes to Mediocrity. Listen to this passage from The Aunt’s Story: The unmarried Theodora Goodman has just had a transcendent and wordless spiritual exchange with a Greek cellist, and receives a letter from her sister, Fanny:

About this time Fanny wrote to say it was going to happen at last. When I was so afraid, dear Theodora, Fanny wrote. But Fanny had made of fear a fussy trimming. Emotions as deep as fear could not exist in the Parrotts’ elegant country house, in spite of the fact that Mr. Buchanan’s brains had once littered the floor. Fanny’s fear was seldom more than misgiving. If I were barren, Fanny had said. But there remained all the material advantages, blue velvet curtains in the boudoir, and kidneys in the silver chafing dish. Although her plump pout often protested, her predicament was not a frightening one. Then it happened at last. I am going to have a baby, Fanny said. She felt that perhaps she ought to cry, and did. She relaxed, and thought with tenderness of the tyranny she would exercise.

‘I must take care of myself,’ she said. ‘Perhaps I shall send for Theodora, to help about the house.’

So Theodora went to Audley, into a wilderness of parquet and balustrades. There was very little privacy. Even in her wardrobe the contemptuous laughter of maids hung in the folds of her skirts.

‘God, Theodora is ugly,’ said Frank. ‘These days she certainly looks a fright.’

—The Aunt’s Story, pp. 112, 113

The bight of his prose attends the jaws of his own horror at the malicious force of the mediocre, the “average”, as embraced by those who turn from the desert.

‘A pity that you huddle,’ said the German. ‘Your country is of great subtlety.’

—Voss, p. 11

Patrick White’s entire oeuvre is a paean to the plight of the man or woman living out of a spiritual vision, or, as Paul Tillich would have it, an “ultimate concern”, assailed by the malevolence, sometimes intended, often inadvertent, of the desert deniers. His personal theology aside, the God of his novels is, in Christian terms, Old Testament, an austere flame lighting the way of the chosen, if not always warming them, and laying waste to those who would choose.

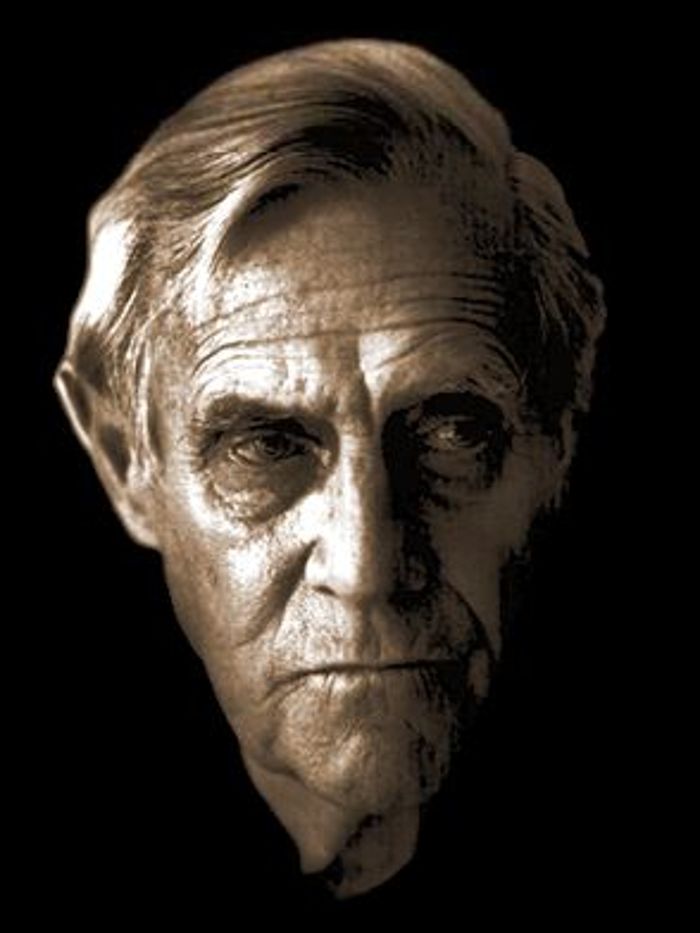

His affinity for those budding on the world’s far and tenuous branches he attributed to his homosexuality. It gave him dispensation, he felt, with the oppressed and reviled. He found it useful, in terms of his artistry, to adopt the rather outmoded notion that his orientation was a kind of gender inversion, a feminine spirit in a man’s body, which allowed him special knowledge and the ability to inhabit many lives. The title of his last completed novel was Memoirs of Many In One.

In my case, I never went through the agonies of choosing between this or that sexual way of life. I was chosen as it were, and soon accepted the fact of my homosexuality. In spite of looking convincingly male I may have been too passive to resist, or else I recognised the freedom being conferred upon me to range through every variation of the human mind, to play so many roles in so many contradictory envelopes of flesh. I settled into the situation. I did not question the darkness in my dichotomy, though already I had begun the inevitably painful search for the twin who might bring a softer light to bear on my bleakly illuminated darkness.

—Flaws in the Glass, pp. 34, 35

Against his disavowal of “the agonies of choosing” and his easy acceptance of the “fact”, his telling self-analysis of having been “too passive to resist”, his taking his sexuality for a “darkness”, suggests a somewhat different, more tormented relationship with himself. Very little of his writing deals explicitly with homosexuality. In all the novels up to The Twyborn Affair (1979), the homoerotic undercurrents are so fleeting, so organic, so subtly rendered, that the closest reader would be forgiven for missing them. But all of his work shoots from Jacob’s hip, wounded in a battle where to be blessed means to finally accept and assimilate (though by no means necessarily to reconcile) one’s own multiple and warring selves, even those which destroy.

Some critics complain that my characters are always farting. Well, we do, don’t we? fart. Nuns fart according to tradition and pâtisserie. I have actually heard one.

—Flaws in the Glass, p. 143

At his centenary, Patrick White’s relevance has increased, it seems, inversely to his readership. He is one of the essential writers. I hope you will read him.

What do I believe? I am accused of not making it explicit. How to be explicit about a grandeur too overwhelming to express, a daily wrestling match with an opponent whose limbs never become material, a struggle from which the sweat and blood are scattered on the pages of anything the serious writer writes? A belief contained less in what is said than in the silences. In patterns on water. A gust of wind. A flower opening. I hesitate to add a child, because a child can grow into a monster, a destroyer. Am I a destroyer? this face in the glass which has spent a lifetime searching for what it believes, but can never prove to be, the truth. A face consumed by wondering whether truth can be the worst destroyer of all.

—Flaws in the Glass, p. 70