On October 10, 2013, the very day Alice Munro was busy winning the Nobel Prize, an altogether different kind of author was busy accruing general obscurity. Eight years after his death, in spite of being one of world literature’s dark giants, in spite of a Nobel of his own, and in spite of it being his centenary, readers of literary fiction everywhere were, quite vigorously, not talking about Claude Simon.

On October 10, 2013, the very day Alice Munro was busy winning the Nobel Prize, an altogether different kind of author was busy accruing general obscurity. Eight years after his death, in spite of being one of world literature’s dark giants, in spite of a Nobel of his own, and in spite of it being his centenary, readers of literary fiction everywhere were, quite vigorously, not talking about Claude Simon.

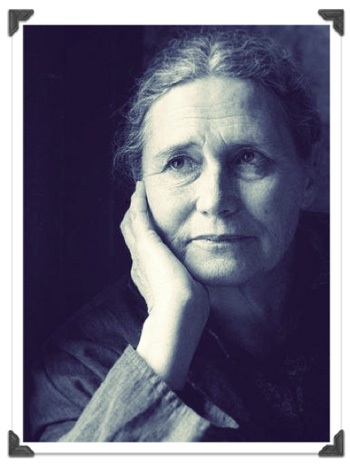

What notice might have come to him on the occasion of his 100th was thwarted by the day’s main event; Canadian letters and the modern short story were finally getting their dues. Hard to say what Claude Simon would have made of Munro’s short, elusive epics. The frailties and vanities we sling against our mortality leap into her narrative net like fish on the far side of Peter’s boat. By contrast, Simon set himself the task of evoking the net of time itself, which holds our mortality, and against which it becomes as piffling a thing as our frailties and vanities. In Munro, the effect is one of piercing intimacy (not to be mistaken for warmth), as if the reader himself had been caught in flagrante delicto, and, rather than being either judged or forgiven, is delivered a parable. In Simon the effect is one of distance and grandeur (often mistaken for coldness), which we read in the way one might take in the paintings on the walls of the caves at Altamira, uncomprehending, yet alerted by rising neck hairs that something approaching the elemental has been uttered.

Munro’s popularity has been like a long-held, well maintained financial portfolio, a steadily rising line over time, weathering the dips and flights of the literary marketplace. No modernist repudiations of the medium for her, nor post-modern repudiations of the reader. She writes as if words can and and do mean something, provided you write about what can be said, which turns out to be quite a lot. This is not to disregard her remarkable innovations of form and her starkly modern view of men and women. But she is the great exponent of the transparent surface. No sentence is either notably long or dryly clipped. No one would call her an adjective whore, but neither are her sentences self-consciously barren. A Munro story is written so that as you’re reading it you have only a shadowy awareness that you are doing so.

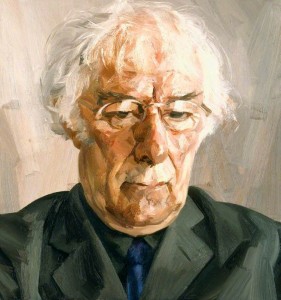

By contrast, reading is often all you can be said to be doing with a text by Claude Simon. This is because he was a writer whose aim was to extend the parameters of writing itself, a dubious undertaking for those who hold to a certain literary prudery. His sentences, elastic with parenthesis and parenthesis within parenthesis, can stretch across many pages, and if you allow your attention to be held, you will be frequently baffled to discover where he’s lead you, and if, rather than being put off, you are fascinated then you may be compelled to backtrack down the narrow path you’ve just cut through the wilderness of often lyric prose in a search for the origins of the narrative present. If you find yourself doing so, in spite of how bewildered you might feel, then you have understood Simon perfectly; his great subject, more than the constants of aging and death, more than the gross and subtitle impact of war, more than the eternal return, is the question: from whence arrives the present?

If, if, and if. It’s no surprise, really, that Simon’s popularity has, from the get go, been a non-starter. When he won the 1985 Nobel Prize, journalists were hard pressed to find any information about him. Calvin Trillin cagily noted, “Susan Sontag better have heard of this guy or there’ll be trouble.” Those few who did know his work were divided as to its merit. Even in his native France, one prominent critic speculated, half in jest and full earnest, whether the Nobel committee, by honoring Simon, had moved “to confirm that the novel has definitely died,” (an arrow Simon himself unfeathered by quoting in his Nobel lecture).

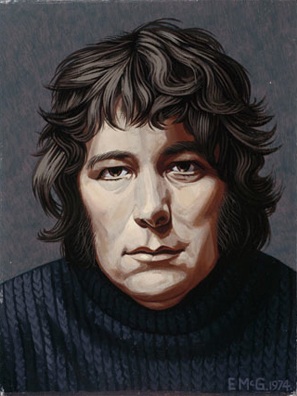

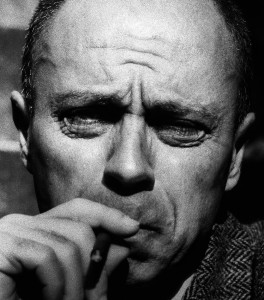

Simon is most commonly linked with a group of mid-20th century French writers known as the nouveaux romanciers, a group which included, most prominently, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, and Michel Butor. Marguerite Duras is also sometimes included, though she resisted the label. The aim of these experimental writers was to evolve a “new novel” which would subverted most of the tenets of the form as it had been received via the 19th century, including plot, character, motivation, and setting, aspects which, to most writers and readers, seemed no less fundamental than the paper on which a book is printed. Simon, like Duras, protested the association, feeling the term itself was misleading. In a rare interview for the Paris Review, he clarified his position: “Since the majority of professional critics do not read the books of which they speak, mountains of nonsense have been spoken and written about the nouveau roman. The name refers to a group of several French writers who find the conventional and academic forms of the novel insupportable, just as Proust and Joyce did long before them. Apart from this common refusal, each of us has worked through his own voice; the voices are very different, but this does not prevent us from having mutual esteem and a feeling of solidarity with one another.”

Simon is most commonly linked with a group of mid-20th century French writers known as the nouveaux romanciers, a group which included, most prominently, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, and Michel Butor. Marguerite Duras is also sometimes included, though she resisted the label. The aim of these experimental writers was to evolve a “new novel” which would subverted most of the tenets of the form as it had been received via the 19th century, including plot, character, motivation, and setting, aspects which, to most writers and readers, seemed no less fundamental than the paper on which a book is printed. Simon, like Duras, protested the association, feeling the term itself was misleading. In a rare interview for the Paris Review, he clarified his position: “Since the majority of professional critics do not read the books of which they speak, mountains of nonsense have been spoken and written about the nouveau roman. The name refers to a group of several French writers who find the conventional and academic forms of the novel insupportable, just as Proust and Joyce did long before them. Apart from this common refusal, each of us has worked through his own voice; the voices are very different, but this does not prevent us from having mutual esteem and a feeling of solidarity with one another.”

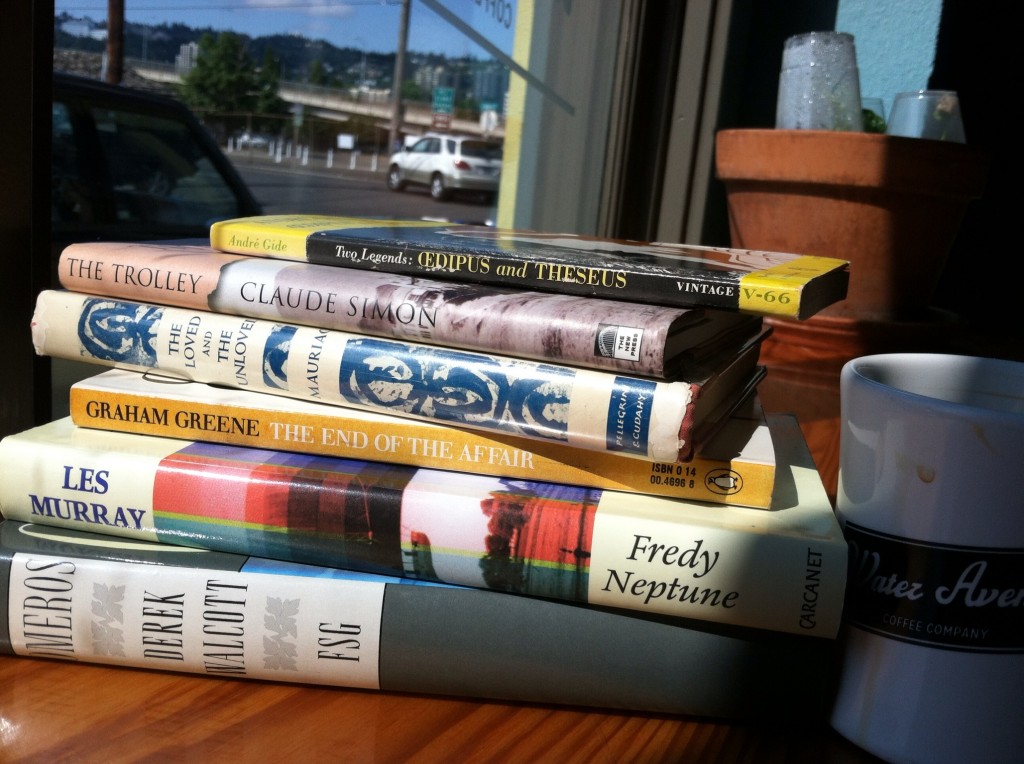

Simon’s reservations notwithstanding, his literary experiments are consistent with the nouveau roman movement. Take, for example, his refusal to analyze causality. His novels are not plotless, as some have suggested, but neither are they linear. Rather than events birthing subsequent events, what happens in a Simon novel emerges, like the constellations, from collections of closely observed tableaux, or from repetitions of an image. For example, in La Routes des Flandres, the image of a horse recurs in many settings. There are the horses mounted by a small unit soldiers, fatally anachronistic in the mechanized theater of the Second World War. There are racehorses, one in particular ridden by Colonel de Reixach, the officer who would later lead this doomed unit and whose young wife is having an affair, or had one, with a jockey who works in his stables and who will later accompany him into battle, riding a horse just behind him. There is a dying horse in the stable where three of the soldiers wait out the night. Most abstractly, there is the recurring image of a dead horse, paradoxically covered in mud despite dry whether. Its first appearance, early in the novel, provides Simon with an opportunity to articulate his whole approach to the novel. The following passage I necessarily quote at some length:

and that must have been where I saw it for the first time, a little before or a little after we stopped to drink, discovering it, staring at it through that kind of half-sleep, that kind of brownish mud in which I was somehow caught, and maybe we had to make a detour to avoid it, and actually sensing it more than seeing it: I mean (like everything lying along the road: the trucks, the cars, the suitcases, the corpses) something unexpected, unreal, hybrid, so that what had been a horse (that is, what you knew, what you could recognize as having been a horse) was no longer anything now but a vague heap of limbs, of dead meat, of skin and sticky hair, three-quarters-covered with mud — Georges wondering without exactly finding an answer, in other words realizing with that kind of calm rather deadened astonishment, exhausted and even almost completely atrophied by these last ten days during which he had gradually stopped being surprised, had abandoned once and for all the posture of the mind which consists of seeking a cause or logical explanation for what you see or for what happens to you: so not wondering how, merely realizing that although it hadn’t rained for a long time — at least so far as he knew — the horse or rather what had been a horse was almost completely covered — as if it had been dipped in café au lait and then taken out — with a liquid grey-brown mud already half absorbed apparently by the earth, as though the latter had stealthily begun to take back what had come from it,

By “not wondering how, merely realizing that”, Simon refuses the softening effect of analysis, leaving this grisly vision hard, relentlessly material. And as the vision repeats throughout the book, we begin to see, glinting off its surface, Simon’s true subject — war. More, the cosmology of one who has survived it: we are all on our way to a vague heap of limbs, dead meat, skin and sticky hair, something like, but inexplicably other than what we are, and nailing down whether an object as incidental as a horse’s corpse, or as universal, was discovered a little before stopping to drink or a little after makes not one wit of difference. In fact one’s wits are notable only for their uselessness, at least when directed toward understanding. One senses rather than sees. The reader’s own wits are further beggared by the change from first person to third midway through this passage. So quickly are we shunted out of Georges’s consciousness and into the author’s that we, like Wily Coyote chasing Road Runner several feet beyond the edge of the cliff, may read along for several lines without quite realizing what has happened. This is Simon’s mimesis; life entails nothing so much as moments just like this. Don’t look down.

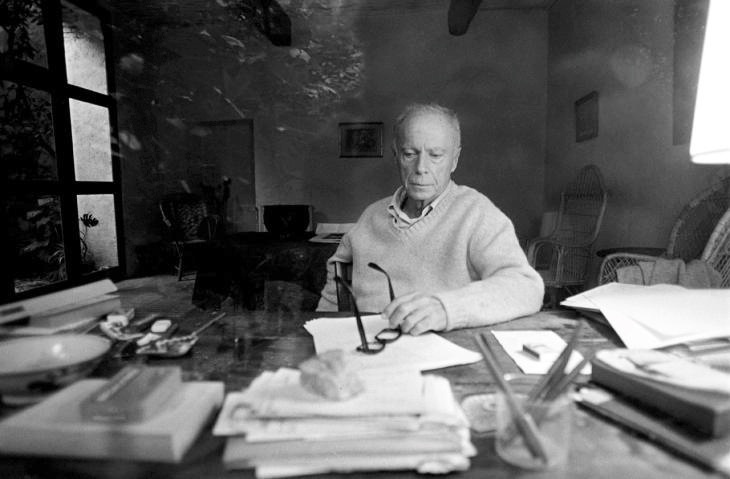

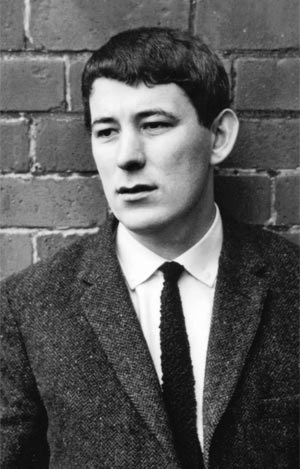

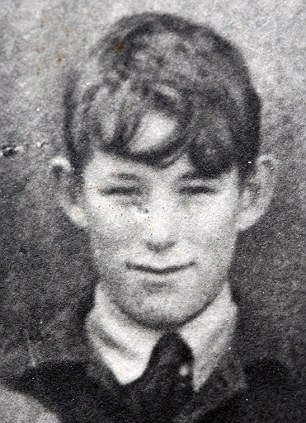

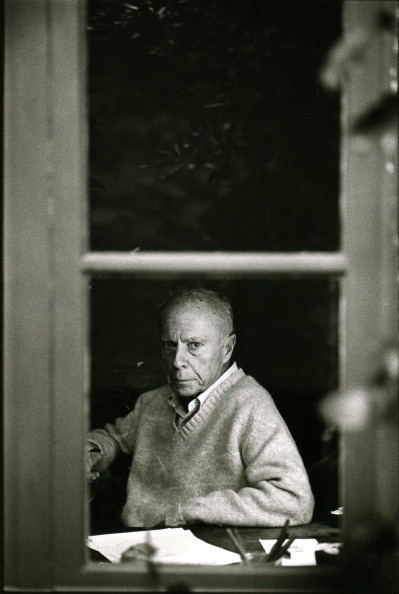

The three novels I have so far read by Simon, The Trolley, The Flanders Road, and The Grass, are either about war or indelibly touched by war. War touched Simon early. World War I had been grinding up the young men of Europe for over two months when he was born on October 10, 1913 in Tananarive (now Antananarivo), Madagascar, and before he was a year old his father, a career cavalry officer, became one of them. His mother brought the family to the home of a relative in Perpignan, a city not far from the Spanish border near the Mediterranean Sea. He was eleven when his mother died of cancer, leaving him in the care of his aunt. He credited the strict Catholic boarding school in Paris to which she sent him with definitively destroying his belief in God. Memories of those earliest years reemerged eight decades later in his final novel Le Tramway (The Trolley).

And it was the same the following summer, except that Maman was no longer there and during the month of October I no longer had to run to catch that four o’clock trolley, having already returned to my school in Paris, which freed me from participating in the traditional autumn move which brought my family to town and from having to listen to the traditional lamentations of my aunt whom this annual return plunged into an ostentatious collapse renewed each year when after four months in the country she found herself back in what she called her “tomb,” i.e. the huge apartment which, though overlooking spacious courtyards and a spacious garden, was, it is true, darkened by the branches of a huge acacia tree;

His first direct involvement with armed conflict came in 1936 when his sympathies with the Spanish Republicans drew him into the Spanish Civil War. But it was with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 that he had his most dramatic experience of war’s absurdity. Like his father, he was drafted into a cavalry regiment, the 31st Dragoons. In a further mirroring of the past, the regiment was sent to the exact same area of the front where his father had been killed twenty six years earlier. One can only speculate that the resonance between his father’s experience and his own launched in young Claude a search for meaning which he finally had to abandon in favor of “not wondering how, merely realizing that”. This kind of repetition, of scene and circumstance across generations, was to become a hallmark of his writing. These recurrences cannot properly be called coincidences, at least not in the Dickensian sense of expediting the plot. But neither are they spiritualized “synchronicities”. Rather, they are treated more in the manner of a painterly motif, the way, say, expanding orders of triangles recur in a painting by Paul Klee. Often he allows a measure of ambiguity as to which iteration of a repeated event is under discussion.

Simon got the starkest imaginable lesson, not only in life’s extreme fragility, but it’s sheer improbability when, at the River Meuse, the 31st Dragoons, picturesquely armed with sabers and rifles and mounted on horseback, were charged with trying to stop German tanks. That his unit would be decimated was a foregone conclusion. That he would survive was not. That he did netted him a formidable, decidedly 20th century vision –of war, of human suffering, of love, and the impossibility of knowing much of anything for certain. Twenty years later he would draw directly from his wartime experience to produce La Routes des Flandres, which would become his most famous novel.

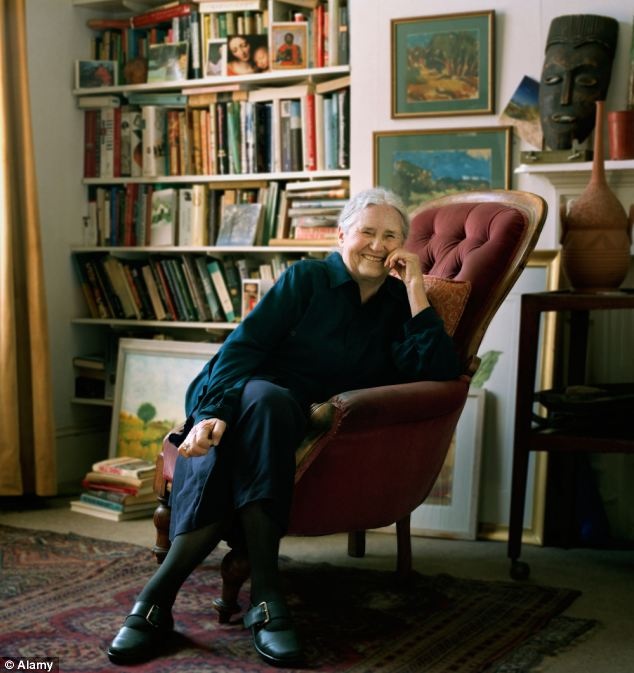

A professor friend once told me, with a campy sneer, that “no one bothers with F. Scott Fitzgerald anymore.” I didn’t believe him then any more than I do now, but his surety (and his unwarranted happiness in delivering it) did raise the problem that, when trying to account for the changing positions of writers in the literary firmament, our logic remains hopelessly Ptolemaic. The eclipse of certain writers – Patrick White, for example – baffles me and I’d love to have someone patiently lay out for me the physical laws, the cycles and epicycles, behind it. On the other hand, that Alice Munro has remained sun-side for so many years seems easy to explain, almost Copernican; she’s a great writer who addresses head on the pain felt in a world whose understanding of gender has undergone major upheavals which the family unit, comprised of the gendered, has often failed to weather. She’s nothing if not perennially relevant.

Claude Simon’s eclipse is perhaps equally understandable, if undeserved. For one thing, the whole nouveau roman project feels dated to us now. Like Schoenberg’s twelve-tone row, it constituted a brilliant, necessary, perhaps even inevitable departure from the way things had been done before, but, while its influence has been widespread and long-lasting, the movement itself was unsustainable. Just as Pierrot Lunaire, glorious listening to the initiated, is unhearable to most, so very few find Robbe-Grillet worth the effort. Simon is a difficult writer, slippery to anyone white-knuckled to the so-called virtue of clarity. But this is no reason not to read him. Difficult, yes, but never unintelligible, and readers who are up on their Faulkner will find nothing in him to deter them. Like Schoenberg, he was an uncompromising artist with an encompassing mind. A careful reading of him not only yields a potent, austere beauty, but, as with the greatest writers, expands forever one’s understanding of just what the art can do.