I.

A peculiar feeling, I wonder if you’ve had it: I stop at a stoplight not far from our house. I know this light well; ten thousand times it’s turned red on me and always stays red at least three beats too long. On the southeast corner, to my left as I wait, is a homegrown karate studio called Progressive Martial Arts. It’s cracked and fallen whitewash gives the small concrete building all the charm of an oft-washed and tumbled dollar bill. A large single pane of glass frames the gi-clad students who chop, kick and roll through their katas. I watch them. My blue Toyota, which needs hubcaps, idles. I watch, and as I watch it all seems altered, made strange, like a photographic negative of this mundane occurrence of which I and my idling car have ten thousand times been a part. Sam has died.

II.

The genius of Cezanne was the flattened canvas. Perspective, he saw, was the great illusion. Mt. St. Victoire becomes a blue density as near as the greens, roses and ochers of the abutting valley forest and towns. Everything in a pervasive visual present tense. Beautiful, but imagine living in such a world.

III.

What settles over me, as surely as the damp florescent light settles over the sweating students inside the studio, is that I will never again stop at this traffic light, watch the karate dance, then continue on the one and a half minutes to my house where Sam waits, where Sam plants the leeks he’s sprouted, where Sam practices Beethoven’s Op. 111., where Sam composes, or arranges American carols for the Symphony’s Christmas concert, where he revolves in the kitchen preparing his special Moroccan lentil soup, where he helps the dog say her prayers over her food bowl, where he will hug me, where we will, all too frequently, fail each others’ tests of patience.

IV.

I’m not, in common parlance, a believer. And yet my love for God, or the idea of God, has so far proved intransigent against all my well-founded protestations. I lay them like dynamite against the stone face of faith and all that blasts forth are chalices and wafers. I’ve learned to accept this. But here’s one thing I cannot accept, that God would pull a stunt like giving someone a long-term, complex, finally terminal illness because it expedites some “divine plan”. Nor do I believe God would do this for some blithe moral imperative, either “for the good” of the sufferer, or, worse, those around him. I could never worship such a self-important busybody. What I believe is that, if there is a God, God inheres somehow in Enormity itself. Death is an enormity. I crumple before it in rage, grief, and terror as before a flaming bush. I want no part of it. But that, to the bush, is neither here nor there. And along with God, or the idea of God, along with the furnace blast, the Holy Danger the meeting of God can sometimes entail, there comes, too, so I am told, the idea of a promised land.

V.

The light changes. I leave the martial dance to the dancers. I drive across flattened space the no distance at all to my front door. The bush breaks into flame. Can’t very well stay out on the front porch.

VI.

Sam. For you, my love:

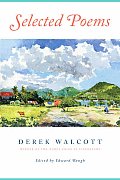

THE SEASON OF PHANTASMAL PEACE

Then all the nations of birds lifted together

the huge net of the shadows of this earth

in multitudinous dialects, twittering tongues,

stitching and crossing it. They lifted up

the shadows of long pines down trackless slopes,

the shadows of glass-faced towers down evening streets,

the shadow of a frail plant on a city sill—

the net rising soundless as night, the birds’ cries soundless, until

there was no longer dusk, or season, decline, or weather,

only this passage of phantasmal light,

that not the narrowest shadow dared to sever.

And men could not see, looking up, what the wild geese drew,

what the ospreys trailed behind them in silvery ropes

that flashed in the icy sunlight; they could not hear

battalions of starlings waging peaceful cries,

bearing the net higher, covering this world

like the vines of an orchard, or a mother drawing

the trembling gauze over the trembling eyes

of a child fluttering to sleep;

it was the light

that you will see at evening on the side of a hill

in yellow October, and no one hearing knew

what change had brought into the raven’s cawing,

the killdeer’s screech, the ember-circling chough

such an immense, soundless, and high concern

for the fields and cities where birds belong,

except it was their seasonal passing, Love,

made seasonless, or, from the high privilege of their birth,

something brighter than pity for the wingless ones

below them who shared dark holes in windows and in houses,

and higher they lifted the net with soundless voices

above all change, betrayals of falling suns,

and this season lasted one moment, like the pause

between dusk and darkness, between fury and peace,

but, for such as our earth is now, it lasted long.

— Derek Walcott

SAMUEL B. LANCASTER, July 9, 1944 – May 11, 2013