WHAT WE MEAN WHEN WE MEAN TO READ

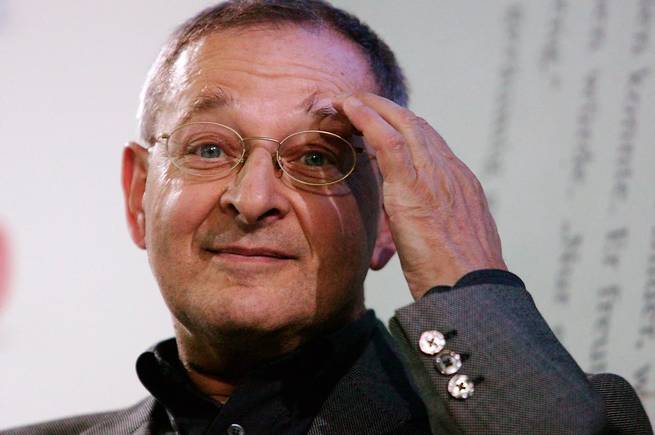

A few years ago I mentioned to a good friend of mine who is a writer that I have never read Midnight’s Children. He didn’t say anything, but it was the kind of not-saying-anything with beats to it. I would say a full eight bars. “I’ve been meaning read it,” I assured him, as his silence began a second phrase, “I just haven’t gotten to it yet.”

Like most readers, I hold in mind a list of books I’ve been meaning to read. It’s a list which includes books I almost certainly will actually read, but also others, many others, which, to the end, I will only ever mean to read. Which is to say, my list is a hedge against mortality. Such lists always are. It is defensive in other ways too: to say I mean to read a certain book – Emma, for instance – salves the moral sting of not having read it. That it is an ever-expanding list paradoxically marks the rise in my sins of omission while shoring up my sense of rectitude; surely knowing what I lack mitigates the lacking.

Though equally unread, not all books I mean to read are equal; some glower from a higher shelf – it seems correct to say that my not having read Don Quixote is a more serious omission than not having read Midnight’s Children – while others have partisans. For example, I distinctly hear Harold Bloom Jewish mothering me for allowing my Shakespeare read-through to stall after Richard III. (“If you can bear living without the poetry of Romeo and Juliet, well then go right ahead. Who am I to say? Clearly nobody ‘t all.” “But Harold. I read it in high school. And I’ve seen the Zeffirelli, and even Leonardo DiCaprio.” “I’m just saying.”) Susan Sontag has been hectoring me from beyond the grave to read The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by Machado de Assis. You know, the 19th century Brazilian novelist. My friend Nathan is concerned that I haven’t read more of the daftly brilliant little novels of César Aira. I, absolutely, mean to read them all. Pax, everyone.

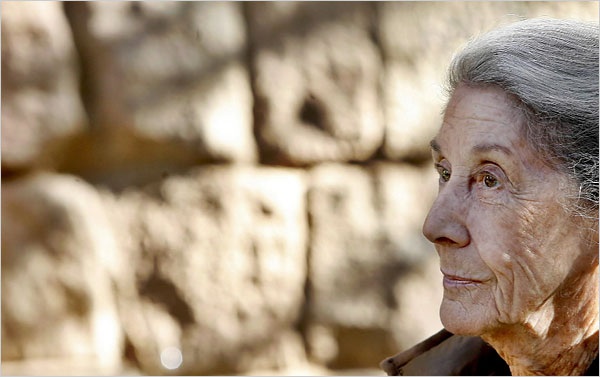

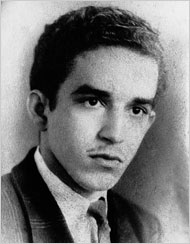

In the wake of Nadine Gordimer’s death, my failure to have read Midnight’s Children began to afflict me, like a cramp, or hunger. As I sifted through material about her, Rushdie’s name kept popping up. As would be expected, she had been among his defenders during the years of the fatwa. In her Nobel lecture, she asserted that “he has done for the postcolonial consciousness in Europe what Günter Grass did for the post-Nazi one with The Tin Drum and Dog Years, perhaps even has tried to approach what Beckett did for our existential anguish in Waiting For Godot[.]” (Who doesn’t love a healthy flirtation with hyperbole, especially when it may prove to be (a) not a flirtation, or (b) not hyperbole.) In 2005, novels by both Gordimer and Rushdie were among the six nominees for the “Best of the Booker”, a one-time award given for the single best novel to have been awarded a Booker Prize in the award’s forty-year history. Gordimer was represented by The Conservationist, Rushdie by Midnight’s Children. Rushdie won.

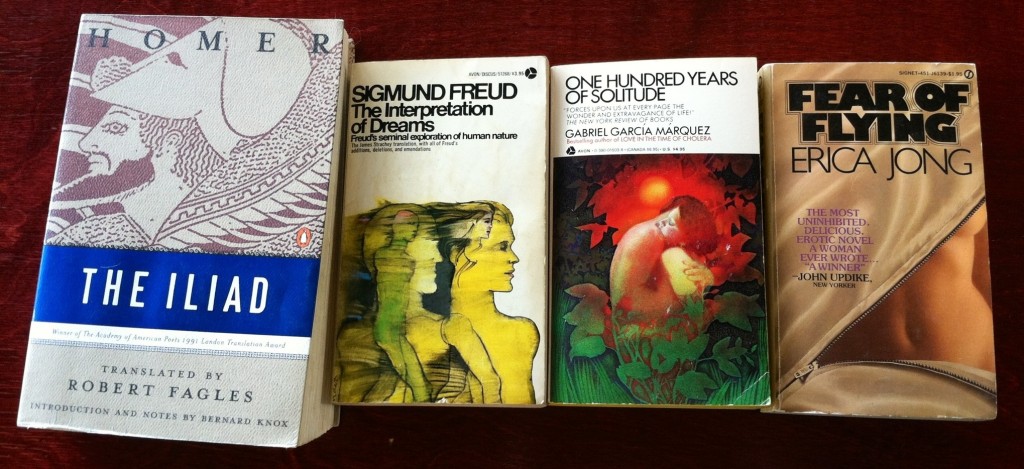

Enough. It was time to leave off meaning to read Midnight’s Children and actually crack the cover. At the time of this writing, I’m about a third of the way through, and can say, unequivocally, it is one of the best thirds of a novel I’ve ever read. I recognize this species of delight; it attended my reading of One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. The Adventures of Augie March also, and, oh yes, A House for Mr. Biswas. The sheer vigor and complexity of this third-of-a-novel disposes me to make a chain of assumptions: 1. that the second two thirds will match the first, 2. that, as expert testimony has it, The Satanic Verses at the very least equals it, and, 3. that the rest of Rushdie’s oeuvre, if not, perhaps, on the same Parnassian level, bears similar markings of genius. All of which leads me to wonder about the hold-up in Stockholm.

There is, to be sure, a logjam of great writers waiting to be laureled. But, as time slips by and Rushdie remains uninvited to Stockholm’s annual highbrow powwow, the Swedish Academy comes ever closer to committing another of its stinkers. There will be much to answer for if they allow him to go the way of Carlos Fuentes, W. G. Sebald, Vladimir Nabokov and Virginia Woolf. Perhaps he is on their own list –of writers they are meaning to honor.

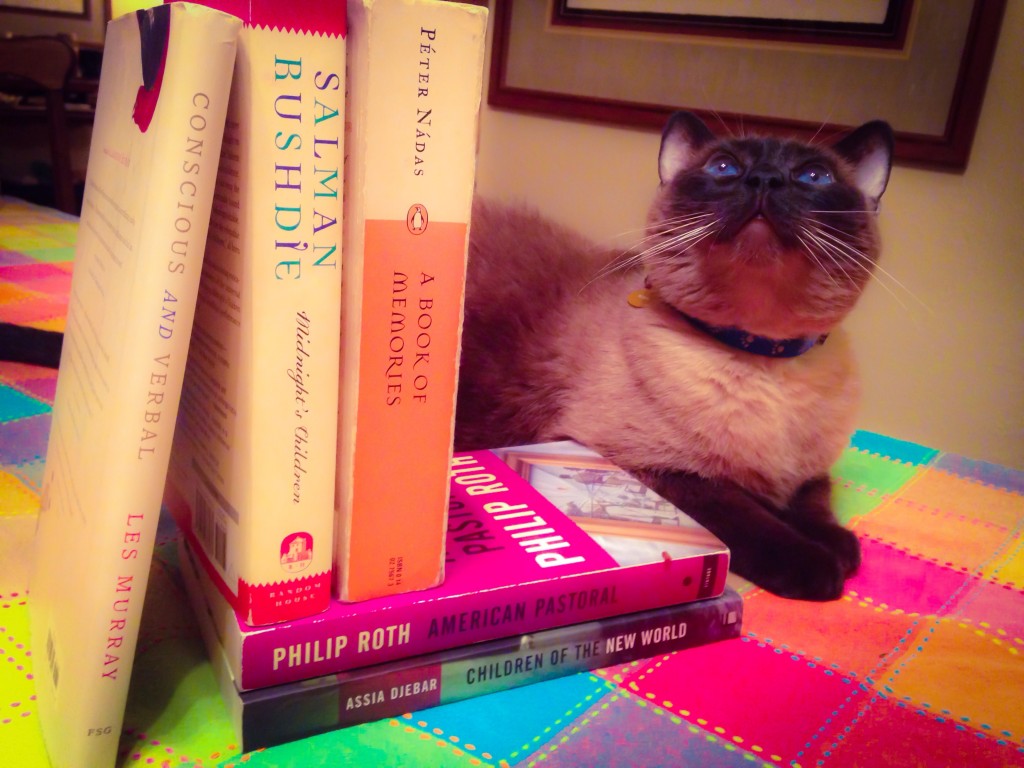

MY SHORTLIST

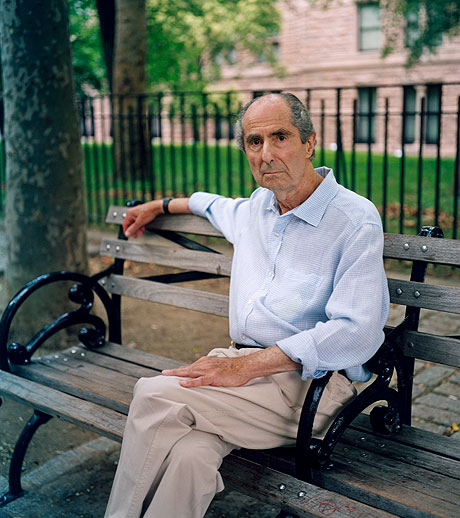

In addition to Salman Rushdie, my 2014 shortlist of Nobelable writers includes three other novelists and a poet. A more stunning group of writers you will never find. Read these experts. Listen, as you read, to how the grief and splendor of living rushes from their words in a spiritual torrent which would wash most of us away if channeled through our own faculties. Listen to how Algerian novelist Assia Djebar evokes the inner life of a “woman of the veil” who has just learned that her husband, a rebel in the Algerian War for Independence, is in grave danger, and chooses to surmount all the prohibitions of her society in order to find and warn him. Australian poet Les Murray is famously querulous, but listen to how in “A Dog’s Elegy” he grows tender, wittily mystical, disarming with image and verbal delight his reader’s defenses against the enormity of death. Listen carefully to Péter Nádas‘s narrator – young, bisexual, Hungarian, hyper-aware – and you’ll hear, in his account of learning to communicate with a young German poet with whom he is in love, the catastrophe of modern Hungary. Listen to Philip Roth, the American perennial, in one of his sublime rants which, as always with him, transcends that descriptor by saying something so heartbreakingly true about human nature that, for all it’s clattering expansiveness, it comes off like Shakespeare. And Salman Rushdie. Listen to him. Am I wrong?

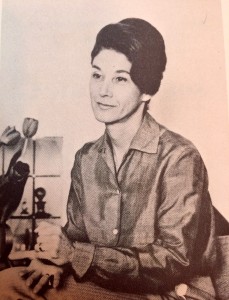

1. Assia Djebar (Algeria)

She’d forgotten the danger itself. In truth, it’s perhaps not that which drove her, but rather a gnawing desire to suddenly know whether she could really spend her life waiting in her room, in patience and love. That’s why she crossed the entire town, bared her presence to so many hostile eyes, and at the end of her trek discovered that she was not only a prey for the curiosity of men — a passing shape, the mystery of the veil accosted by the first glance, a fascinating weakness that ends up being hated and spat upon — no, she now knows that she existed. She’s been inhabited by one inflexible thought that has made her untouchable. “Get to Youssef! He’s in danger,” she had repeated. “But is he, really?” she ended up wondering when she found herself alone on the curb surrendering to, or even beyond, the same fruitless waiting. “Won’t he first of all be shocked to see me here, out in the street?” No, the danger is real.

(Children of the New World)

2. Les Murray (Australia)

A Dog’s Elegy

The civil white-pawed dog who’d strain

to make speech-like sounds to his humans

lies buried in the soil of a slope

that he’d tear down on his barking runs.

He hated thunder and gunshot

and would charge off to restrain them.

A city dog too alive for backyards,

we took him from the pound’s Green Dream

but now his human name melts off him;

he’ll rise to chase fruit bats and bees;

the coral tree and the African tulip

will take him up, and the prickly tea trees.

Our longhaired cat who mistook him

for an Alsatian flew up there full tilt

and teetered in top twigs for eight days

as a cloud, distilling water with its pelt.

The cattle suspect the Dog lives

but three kangaroos stood in our pasture

this daybreak, for the first time in memory,

eared gazing wigwams of fur.

(Conscious and Verbal)

3. Péter Nádas (Hungary)

But as he listened to me, a radically different process was also taking place in him: as usual, he kept correcting my grammatically faulty sentences, he did this almost unawares, it had become an unconscious habit between us; in fact, he was the one who shaped my sentences, gave them the proper structure, incorporated them into the neat order of his native language, I had to rely on his expropriated sentences to work my way through my linguistic rubble, had to use his sentences to tell my story, and didn’t even notice that some of these jointly produced sentences were repeated two or three times, their place and value reshuffled, before reaching intelligible form.

It was as if I had to use my own past to coax the story of his past out of him. I didn’t think of it then, but now I believe we needed these evening walks not just for the exercise but to relate to the world around us — which we both felt, though for different reasons, to be cheerless and alien — and to do it in a way that this same world would not be aware of what we were doing.

(A Book of Memories)

4. Philip Roth (United States)

You fight your superficiality, your shallowness, so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance, as untanklike as you can be, sans cannon and machine guns and steel plating half a foot thick; you come at them unmenacingly on your own ten toes instead of tearing up the turf with your caterpillar treads, take them on with an open mind, as equals, man to man, as we used to say, and yet you never fail to get them wrong. You might as well have the brain of a tank. You get them wrong before you meet them, while you’re anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you’re with them; and then you go home and tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again. Since the same generally goes for them with you, the whole thing is really a dazzling illusion empty of all perception, an astonishing farce of misperception. And yet what are we to do about this terribly significant business of other people, which gets bled of the significance we think it has and takes on instead a significance that is ludicrous, so ill-equipped are we all to envision one another’s interior workings and invisible aims? Is everyone to go off and lock the door and sit secluded like the lonely writers do, in a soundproof cell, summoning people out of words and then proposing that these word people are closer to the real thing than the real people we mangle with our ignorance every day? The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong. Maybe the best thing would be to forget being right or wrong about people and just go along for the ride. But if you can do that — well, lucky you.

(American Pastoral)

5. Salman Rushdie (Great Britain)

Why had she married him?—For solace, for children, But at first the insomnia coating her brain got in the way of her first aim; and children don’t always come at once. So Amina had found herself dreaming about an undreamable poet’s face and waking with an unspeakable name on her lips. You ask: what did she do about it? I answer: she gritted her teeth and set about putting herself straight. This is what she told herself: “You big ungrateful goof, can’t you see who is your husband now? Don’t you know what a husband deserves?” To avoid fruitless controversy about the answers to these questions, let me say that, in my mother’s opinion, a husband deserved unquestioning loyalty, and unreserved, full-hearted love. But there was a difficulty: Amina, her mind clogged up with Nadir Khan and his insomnia, found she couldn’t naturally provide Ahmed Sinai with these things. And so, bringing her gift of assiduity to bear, she began to train herself to love him. To do this she divided him, mentally, into every single one of his component parts, physical as well as behavioral, compartmentalizing him into lips and verbal tics and prejudices and likes…in short, she fell under the spell of the perforated sheet of her own parents, because she resolved to fall in love with her husband bit by bit.

(Midnight’s Children)

The 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature will be awarded soon. Share with us, here at The Shelf: Who do you think will win? (My bets are on Assia Djebar this year.) Who do you think should win?