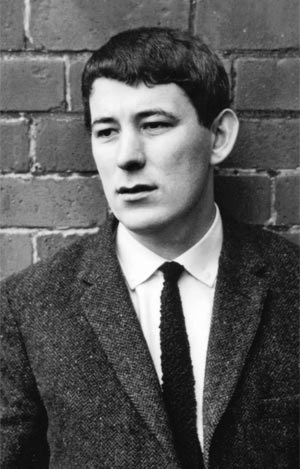

I first heard Seamus Heaney’s name as an undergraduate in a seminar on Norse Mythology. The class had nothing to do with him, but the visiting professor, a rosy-cheeked, crinkly-eyed British poet and translator named Kevin Crossley-Holland, clearly wanted it to have something to do with him, if only for a moment. I have no memory of what he said about him, except that he was one of the foremost poets writing in English, what poem he referenced, except that he intoned its lines with an artful facsimile of naturalness, or in what context he mentioned him, except that it had nothing to do with Heaney’s and Ireland’s importance to one another.

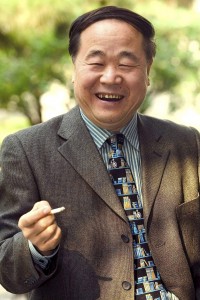

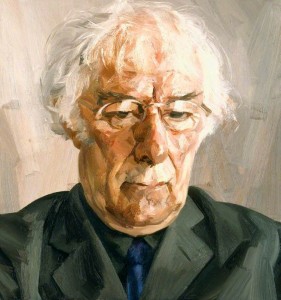

A few years later, when I saw Heaney’s name and picture towards the bottom of the front page of the paper and read that he’d won the Nobel Prize, I remembered again that seminar. I remembered that for my final presentation I managed, much to the puzzlement of my classmates and the evident bemusement of Crossley-Holland, to work in a bit of the fourth movement of Sibelius’s Second Symphony because for me it evoked something of Wotan, but really because, like Crossley-Holland’s bringing Heaney to bare on that class, I wanted the music to be there, and niceties such as Sibelius’s own affinity for Finnish mythology as opposed to Norse counted for nothing.

A few years later, when I saw Heaney’s name and picture towards the bottom of the front page of the paper and read that he’d won the Nobel Prize, I remembered again that seminar. I remembered that for my final presentation I managed, much to the puzzlement of my classmates and the evident bemusement of Crossley-Holland, to work in a bit of the fourth movement of Sibelius’s Second Symphony because for me it evoked something of Wotan, but really because, like Crossley-Holland’s bringing Heaney to bare on that class, I wanted the music to be there, and niceties such as Sibelius’s own affinity for Finnish mythology as opposed to Norse counted for nothing.

As I stood at the kitchen counter reading the column announcing Heaney’s win, I remember feeling keen that he was a poet. As much as I loved poetry, I loved loving poetry even more. I always wanted to be a poet. By that I mean that in high school I wanted to be Percy Bysshe Shelley, a desire which, with adolescent urgency, I soon transferred onto T. S. Eliot. The thought of writing something as happily sonorous as “In the room the women come and go/ Talking of Michelangelo”, was a reason to pull myself out of bed in the morning. Who cared what it meant. In college I fell head over heals for Auden –his poetry, certainly, but more Auden himself, or rather the Auden I constructed out of bits of myself, my insecurities, my fantasies of meriting a face like that (without, let it be understood, having to bare the face itself); I fetishized what I imagined to be his urbane relationship with his world, his sexuality, his fellows, his apparent capacity to hold in balance being at once supremely disabused and wide open, someone capable of a quatrain like “How should we like it were stars to burn/ With a passion for us we could not return?/ If equal affection cannot be,/ Let the more loving one be me.” Neruda, too, I used to gild my mirror on the wall. What better than to be a person who loved Pablo Neruda? How different, I imagined, my life would be had I the internal reserves to say “I want/ To do with you what spring does with the cherry trees.” Heaney, at the time of his Nobel, I had not yet read, so I had no idea how he would fit into my accrual of sensibility. But I remembered Crossley-Holland’s reverence and thought him a good bet.

When I finally began to read him, I quickly realized he would not yield so easily to any narcissistic projects. I came across stanzas like this one:

When I finally began to read him, I quickly realized he would not yield so easily to any narcissistic projects. I came across stanzas like this one:

Tonight, a first movement, a pulse,

As if the rain in a bogland gathered head

To slip and flood: a bog-burst,

A gash breaking open the ferny bed.

Your back is a firm line of Eastern coast

And arms and legs are thrown

Beyond your gradual hills. I caress

The heaving province where our past has grown.

I am the tall kingdom over your shoulder

That you would neither cajole nor ignore.

Conquest is a lie. I grow older

Conceding your half-independent shore

Within whose borders now my legacy

Culminates inexorably.

(from “Act of Union”)

None of my previous poetic loves could give me a leg up on this. Its not a “difficult” poem per se. That Britain and Ireland are two land masses interfering erotically with one another is not hard to deduce. And with words like “pulse”, “flood”, “gash”, “ferny bed”, “hills”, “caress”, “culminates”, you would think, wouldn’t you, that some erogenous brain center would get at least a synaptic tweak. But the sex here is cold, Neruda on ice. In any case, it wasn’t really the means of his poetry that eluded me. It was the ends. What was Heaney saying by saying what he was saying?

In retrospect, the reason for my block was twofold: First, unlike the poetry I had typically found simpatico, which tended to be romantic, even in Auden at his crustiest, Heaney made no appealing, romantic gestures like “His soul stretched tight across the skies/That fade behind a city block”. No self-involved gasps like “Make me thy lyre, even as the forest is:/ What if my leaves are falling like its own?” Instead we get “Conquest is a lie. I grow older/ Conceding your half-independent shore/ Within whose borders now my legacy/ Culminates inexorably”. Whatever it means, it’s not very nice.

My second block stemmed from a loose and grossly under-informed grasp of modern Irish history. I knew that Ireland was one of the geopolitical Earth’s hot spots, a place where Catholics and Protestants vigorously eschewed Christian behavior with one another, and that the strife was between the North and South. But this is all I could have said. I didn’t actually know which faction was in the North and which South. I didn’t get it that for some the fight was about religious hatred and others political justice, or that masked members of the IRA pulled people from buses for massacre, or that Protestant loyalists blew up civilians in Belfast pubs, or that Britain had responded with violence to the nationalist’s demands for basic civil rights. I had no head for the why of the conflict or its duration. Finally, and most compromisingly, I did not even know to entertain the question, let alone approach comprehension, what it really meant to an Irishman, of whatever religious stripe, to be Irish.

Today I know a little more about the tragedy of modern Ireland, and I am aware of the indelible thumbprint left by the Irish on Western culture. This makes me a better reader of Heaney’s poetry, but it’s not why I now love him. I love him because he invites me to adopt a more vulnerable way of meeting the world. I have always been hungry to know what, on Earth, is going on, only in those flushed post grad years I conceived this as a largely self-referential task, realizing my “gifts”, deepening my skills, learning the star chart of my sensuality. Heaney’s poetry invites me to use all that as a starting point from which to move into a much broader landscape, wilder, often hostile, always awash in grandeur. When he writes “Tonight, a first movement, a pulse,” I need no context, I know what that is, and not only through concupiscence. It’s that thing we all feel in our bodies when we find ourselves alone in our rooms at night and realize the world has waxed strange. By the time I arrive at “A gash breaking open the ferny bed” he’s tumbled me into a new and violent place, a place where I, terrifyingly, may not signify at all, like when, as a child, I first became aware of the erotic life of my parents. In the very next lines, “Your back is a firm line of Eastern coast/ And arms and legs are thrown/ Beyond your gradual hills,” I’ve been brought to crouch behind a wall, or a shrub, from where I am to witness something grave and large and against which all my supposed gifts and skills will count for nought. What, after all, is possible where implacable kingdoms loom tall over shoulders? That this is England and Ireland is only intellectually significant as the emotion has made a “bog-burst” through cartographic constraints. By the last two words of the stanza, “Culminates inexorably,” all my narcissistic projects have splintered and fallen in the face of what, on Earth, is really going on.

Today I know a little more about the tragedy of modern Ireland, and I am aware of the indelible thumbprint left by the Irish on Western culture. This makes me a better reader of Heaney’s poetry, but it’s not why I now love him. I love him because he invites me to adopt a more vulnerable way of meeting the world. I have always been hungry to know what, on Earth, is going on, only in those flushed post grad years I conceived this as a largely self-referential task, realizing my “gifts”, deepening my skills, learning the star chart of my sensuality. Heaney’s poetry invites me to use all that as a starting point from which to move into a much broader landscape, wilder, often hostile, always awash in grandeur. When he writes “Tonight, a first movement, a pulse,” I need no context, I know what that is, and not only through concupiscence. It’s that thing we all feel in our bodies when we find ourselves alone in our rooms at night and realize the world has waxed strange. By the time I arrive at “A gash breaking open the ferny bed” he’s tumbled me into a new and violent place, a place where I, terrifyingly, may not signify at all, like when, as a child, I first became aware of the erotic life of my parents. In the very next lines, “Your back is a firm line of Eastern coast/ And arms and legs are thrown/ Beyond your gradual hills,” I’ve been brought to crouch behind a wall, or a shrub, from where I am to witness something grave and large and against which all my supposed gifts and skills will count for nought. What, after all, is possible where implacable kingdoms loom tall over shoulders? That this is England and Ireland is only intellectually significant as the emotion has made a “bog-burst” through cartographic constraints. By the last two words of the stanza, “Culminates inexorably,” all my narcissistic projects have splintered and fallen in the face of what, on Earth, is really going on.

Heaney is a great poet because he invites his readers into this, at best, difficult world, but doesn’t abandon them to it. However fraught the place to which he carries us, we are carried still, held in the arms of his artifice. The language of a Heaney poem is clear and high and beautiful and deeply moral, even when speaking of the slashed throat of a third century man discovered preserved in a peat bog:

The head lifts,

The head lifts,

the chin a visor

raised above the vent

of his slashed throat

that has tanned and toughened.

The cured wound

opens inwards to a dark

elderberry place.

Who will say ‘corpse’

to his vivid cast?

Who will say ‘body’

to his opaque repose?

(from “Grauballe Man”)

In his remarkable Nobel lecture, he speaks to this very quality of vulnerability chaperoned by beauty in all “necessary poetry”, poetry whose raison d’être is “to touch the base of our sympathetic nature while taking in at the same time the unsympathetic reality of the world to which that nature is constantly exposed”. By these lights, necessary poetry allies itself with that in me which once longed to take on the guise of Auden, and which needed the Sibelius Second to be about Woton because it needed Sibelius, period. These are signal flares from my sympathetic nature. Poetry is the large, warm hand that guides this nature into the great and difficult world from which it must, at last, draw sustenance.

As I write this, I can’t shake the feeling that Shelly, Eliot, Auden and Neruda are staring at me from whatever heaven they have found, and biting their tongues. “Is that not what we all were about?” they say. Seamus Heaney, newest among them, says gently, “Let him rant.”