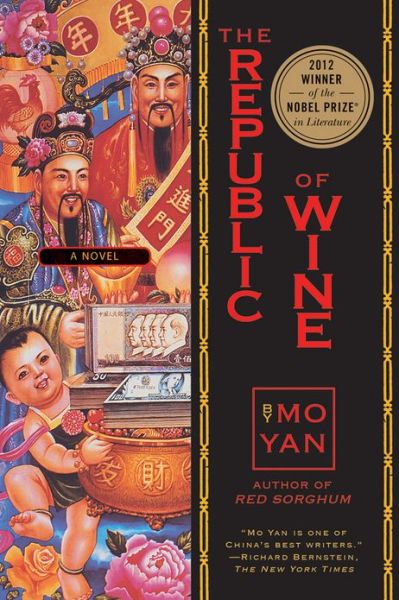

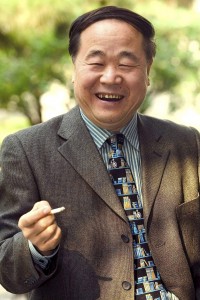

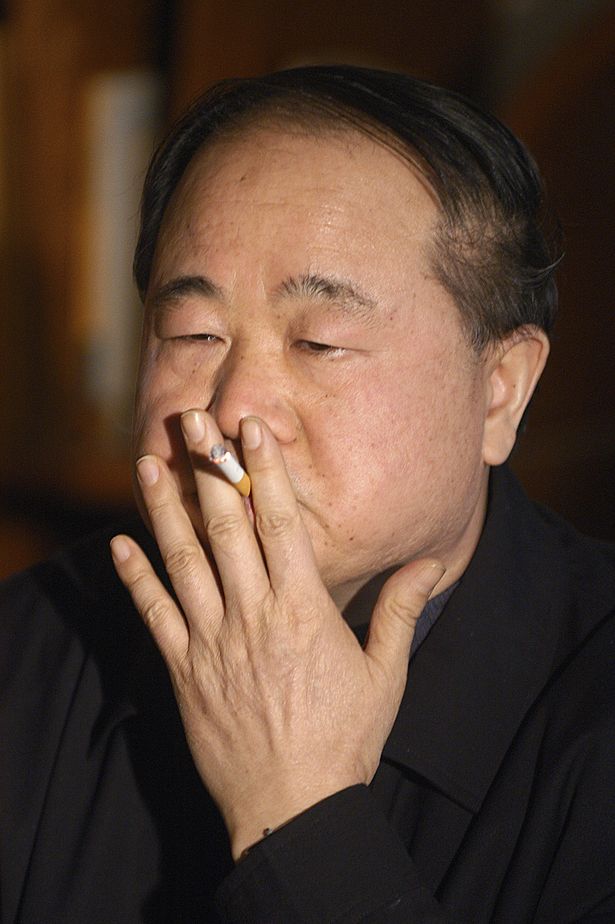

Societies in which arranged marriages are still prevalent must wonder what all the brouhaha was about when Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature last year. In some quarters (China) his win was celebrated as if he was a conquering hero on the order of, say, Genghis Kahn. Others, of which yours truly is one, felt his win to indicate, if not actual malignancy at work in the universe, then at least mindless absurdity at work in Stockholm, not least because of his slapdash writing. But societies with arranged marriages must view all this backing and forthing as a curious instance of democratic vanity. In such societies, families pair off boys and girls for marriage, often very early in life, at some point the boy and girl are told of the arrangement, and that is the end of it until the wedding day, unless, as in some cultures, the wedding day is the day of revelation. The pair is either happy about it or not, much to the indifference of those who’ve chosen for them. For it to work – and in many places it has long worked rather well – there must be a broad-based acceptance of a cosmos in which things are given or taken without much regard for the wishes or agency of the ones receiving or yielding. It’s only when love, a human universal, turns to regard itself, and in doing so steps beyond its provenance in the body to style itself as a compelling thought process capable of making vital decisions that people begin to get touchy about who’s being foisted on them.

Societies in which arranged marriages are still prevalent must wonder what all the brouhaha was about when Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature last year. In some quarters (China) his win was celebrated as if he was a conquering hero on the order of, say, Genghis Kahn. Others, of which yours truly is one, felt his win to indicate, if not actual malignancy at work in the universe, then at least mindless absurdity at work in Stockholm, not least because of his slapdash writing. But societies with arranged marriages must view all this backing and forthing as a curious instance of democratic vanity. In such societies, families pair off boys and girls for marriage, often very early in life, at some point the boy and girl are told of the arrangement, and that is the end of it until the wedding day, unless, as in some cultures, the wedding day is the day of revelation. The pair is either happy about it or not, much to the indifference of those who’ve chosen for them. For it to work – and in many places it has long worked rather well – there must be a broad-based acceptance of a cosmos in which things are given or taken without much regard for the wishes or agency of the ones receiving or yielding. It’s only when love, a human universal, turns to regard itself, and in doing so steps beyond its provenance in the body to style itself as a compelling thought process capable of making vital decisions that people begin to get touchy about who’s being foisted on them.

People who direct their love towards books tend to become deeply attached to certain authors. For such counterculturists, the Nobel Prize can feel rather barbaric. Like an arranged marriage. Once we’ve been handed our winner – because it does feel somehow like a bestowal – our feelings about Stockholm’s choice, approval or dismay, become more at issue than the choice itself. In other words, it becomes all about us.

In about a week that famous secular conclave will meet to decide who to shack us up with this year. Busybody pundits are giving themselves little orgasms asking who, or what kind of writer, it will be. Will it be a captivating storyteller who ravishes her readers with a gorgeously over-stuffed vision of humanity, someone in the line of, say José Saramago or Gabriel Garcia Marquez, or will it be someone whose rewards are cloistered behind a wall of aesthetic that will keep him a rather arcane fetish for a few, someone akin to Claude Simon or Samuel Beckett? Will it be a curiosity, like Dario Fo, or a well known literary force, e.g. Saul Bellow? Another bony Eastern European to join Herta Müller, or a non-colonial African to keep Wole Soyinka company? Will the political objective driving the choice be baldfaced, as with Orhan Pamuk, or restrained, as with Tomas Tranströmer? Male or female? Novelist? Poet? Playwright? Someone uncharacteristically category-defying?

These questions, while entertaining, are really of only passing interest, in the end not much different than church basement gossip. The real question, or the only one that matters to any of us inclined to take an interest, is whether or not when we lift the veil and gaze upon who has been chosen for our regard, we find the face lovely or dispiriting.

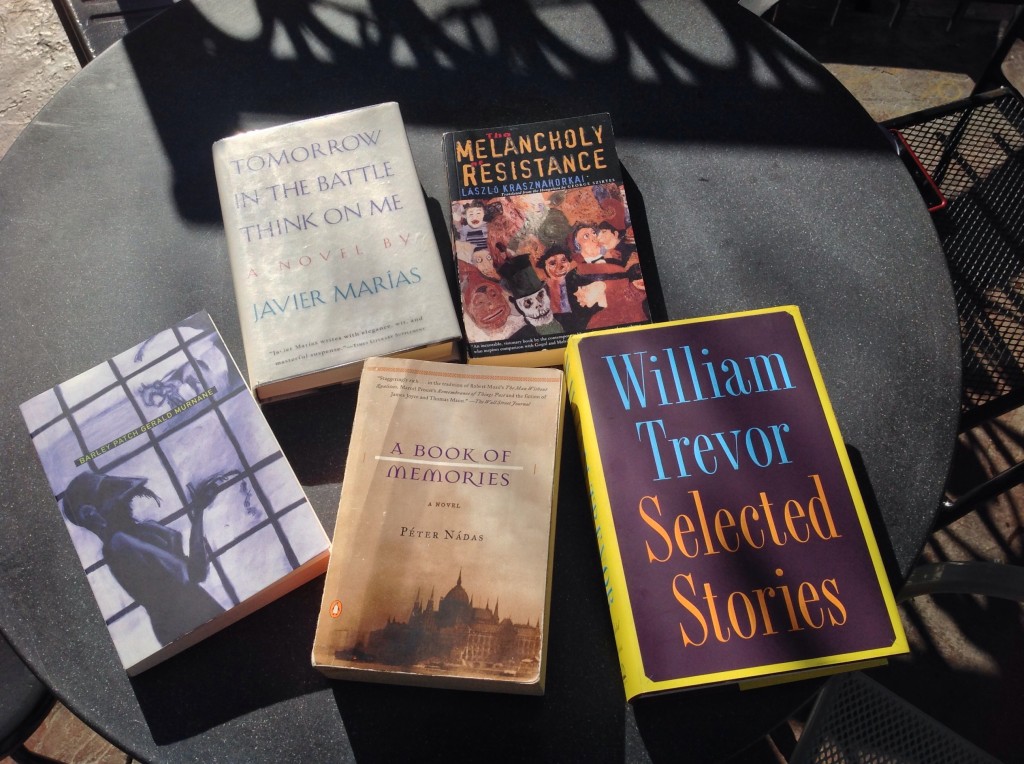

Here is a list of five authors I would be more than happy to live with should Stockholm choose them. There are, of course, many others. Philip Roth and Alice Munro don’t appear on my list this year even though I would probably pee myself if either of them made the cut. But they’ve been on my short list for the past two years, and I decided to only put forth candidates who I’ve not put forth before. I would be fascinated if either Kenya’s Ngugi wa Thiong’o or Algeria’s Assia Djebar won, and am eager to get to know their work, but on this list you’ll find only writers I’ve actually read. The Nobel literature prize is always geopolitically interesting: On my list this year, two are Hungarian, one is Australian, one Irish, one Spanish. I’m struck that all my choices are men, and all fiction writers. Call my list one-sided, but these guys are all as good as it gets. I’ve listed them alphabetically because if I were to rank them in order of who I most want to win, they’d all have to pile into a rather ill-suited cluster in the first spot. Along with their names, I offer you a passage from each of their bodies of work. You decide who you would choose. I’m sure I can’t.

László Krasznahorkai (Hungary)

László Krasznahorkai (Hungary)

Rubbish. Everywhere he looked the roads and pavements were covered with a seamless, chinkless armour of detritus and this supernaturally glimmering river of waste, trodden into pulp and frozen into a solid mass by the piercing cold, wound away into the distant twilight greyness. Apple cores, bits of old boots, watch-straps, overcoat buttons, rusted keys, everything, he cooly noted, that man may leave his mark by was here, though it wasn’t so much this ‘icy museum of pointless existence’ that astonished him (for there was nothing remotely new about the particular range of exhibits), but the way this slippery mass snaking between the houses, like a pale reflection of the sky, illuminated everything with its unearthly, dull, silvery phosphorescence.The awareness of where he was exercised an increasingly sobering effect on him—he had by no means lost his capacity for calm appraisal—and as he continued to appraise, as if from a considerable eminence, the monstrous labyrinth of filth, he grew ever more certain that, since his ‘fellow human beings’ had utterly failed to notice this flawless and monumental embodiment of doom, it was pointless talking about a ‘sense of community’. It was, after all, as if the earth had opened up beneath him, revealing what lay underneath the town, or, and he tapped the pavement with his stick, as if some terrible putrescent marsh had seeped through the asphalt to cover everything.

from: The Melancholy of Resistance

“People used to venerate them or at least their memory, and they would go and visit their graves with flowers, and their portraits would preside over their homes,” I thought, “people spent a period in mourning and everything stopped for awhile or slowed down, the death of someone affected the whole of life, the dead person really did take with them a part of the lives of their loved ones and, consequently, there wasn’t such a separation between the two states, they were related and they were less frightening. Now people forget the dead as if the dead were plague victims, sometimes they use them as shields or dunghills in order to blame them and make them responsible for the terrible situation in which they have left us, often they are loathed or they receive only acrimony and reproaches from their heirs, they departed too soon or too late without preparing the ground for us or without leaving us free, they continue being names but not faces, names to which all manner of villainies and cowardices and horrors are imputed, that’s the current tendency, and thus they do not find rest even in oblivion.”

from: Tomorrow in the Battle Think On Me

“On that day it appeared that the whole state was alight. At midday, in many places, it was dark as night. Seventy-one lives were lost.” The previous sentences are from a report of a royal commission that followed the bushfires of January, 1939, in the state of Victoria. The day when the bushfires were at there worst was known afterwards as Black Friday. By chance, it was the day when my youngest aunt left the convent that would have overlooked, among much else, the paddock whereon would be lain down fifteen years later a certain street beside which would be built twelve years later again the house in which my aunt’s oldest nephew would live for at least forty years and would write books of fiction, one of the last of which would include a passage in which the narrator, who was wholly lacking in imagination, would report mere details in the hope that fiction truly was, as someone once claimed, the art of suggestion and that some at least of his readers might intuit or divine or suppose, if not imagine, some little of what his aunt had seen or felt on the day when she left the convent where she had hoped to live for the rest of her life.

from: Barley Patch

A shipwrecked person whose feet desperately seek something solid to keep him afloat will grab at anything, anyone, the first available object, and if it buoys him up he won’t let it go, he’ll swim with it,and after a time he’ll see he has nothing else! just this? and the object will grimly concur, yes, just this, nothing else! and the implacable impulse of self-preservation, joined of course by rationalization and mystification, will have him believe that the object that drifted his way by chance was really his, it chose him and he chose it, and by the time the sheer force of unrelenting waves casts him onto the shore of mature adulthood, his faith and gratitude will have made him worship what was accidental and adore fortuity, but can his rescue from destruction be really accidental?

from: A Book of Memories

Growing up in the listless nineteen-eighties, Celia Normanton knew her father well, her mother not at all. Mr. Normanton was handsome and tall, with steely gray hair brushed carefully every day so that it was as he wished it to be. His shirts and suits gave the impression of being part of him, as his house in Buckingham Street did, and the family business that bore his name. Only Mr. Normanton’s profound melancholy was entirely his own. It was said by people who knew him well that melancholy had not always been his governing possession, that once upon a time he had been carefree and a little wild, that the loss of his wife – not to the cruelty of an early death but to her preference for another man – had left him wounded in a way that was irreparable.

from: “The Women”