Allegory, the use of symbolic figures or actions to convey abstract, often moral, principles or ideas, can, in the hands of a skillful writer, add a layer of meaning to a narrative. But, how skilled that writer must be lest characters shed flesh and blood and become mere signifiers, “Truth” or “Avarice” in all but name. How subtle, lest every action, every gesture become a schoolyard tattler pointing a righteous finger at its own meaning. When allegory infects a narrative’s structure, it becomes as false and awkward as “asset enhancing” underwear, worn to trick the eye into thinking there is something there when there isn’t. The Victorian bustle is perhaps the most famous example, worn by women of all shapes and sizes as an “allegory” of their own sexual identity. William Golding has often been faulted for being an allegorist, a designer of literary bustles.

One need read no further than the title of The Spire to suspect confirmation of this criticism. If the novel turned out to be about nothing other than what the cover claims, then we could already assume the author has used his Everyman quill to give us a good medieval talking to. At its most mundane, a spire is an allegorical piece of architecture. Even without invoking Freud, it is a symbolic declaration of power, void of function apart from its meaning. And when the bespired building is a Christian cathedral, the allegorical gruel thickens. The general upward thrust of the Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe, and of their spires in particular, was intended to lift the people’s eyes upward, releasing their attention from the ground where they labored, and into which their lives were headed, and to remind them of the direction their souls would take at the end of a life of obedience to the church. The higher the spire, the wealthier the diocese, or the more wealthy it was perceived to be, and therefore, the more favored by God.

And then, so sorry, there is Freud.

I read The Spire (1964), William Golding’s fifth published novel, the first time at least, with an ear out for what could be problematic. So primed, the problematic obliged. Jocelin, Golding’s protagonist, is the quintessential out-of-touch clergyman with, oh dear, a divine vision. He believes God has ordered him to build a four hundred foot spire on the cathedral of which he is dean. Can you say, “Pride”? Only, guess what, the building has foundations barely sufficient to support itself as it is, spireless. A spire, we are told, must “go down as far as it goes up,” surely the moral of something or another. The master builder, Roger Mason (Can’t fault the name. People in the middle ages were often identified by their trades), digs a deep pit at the church’s crossing to prove to Jocelin the lack of adequate foundations. Not only is his point made, but, it turns out, the earth creeps; the church – wait for it – has been built on shifting sands. Already there is enough portent here to tempt even the greatest writer’s heavy hand. But then, how about those four pillars on which the weight of the tower will rest. They are far too narrow. Joceline attributes all arguments against building the spire to Roger’s lack of faith and forces his vision towards completion. As it rises, ludicrous, priapic, and the pressure on the pillars increases, they being to “sing”, emitting a high pitched “eee”. And then they begin to bend, as solid stone should never do. As it turns out, their apparent solidity is the common illusion of ashlar stone, that is, a veneer of squared, “dressed” stone fronting rubble. To top it all off, so to speak, the obsessed Dean is observed at one point holding the model of the spire close, and stroking it. Oh, honestly!

Another common criticism of Golding is that he is ill-adept at depicting complex adult human relationships. The Spire could be read as corroborating evidence. The characters who flicker in and out of Joceline’s line of vision are composed of outlines, gestures. Father Anselm, Joceline’s tight-lipped confessor, is little more than a posture. Goody Pangall, wife of the crippled and impotent cathedral servant, and the object of Joceline’s insufficiently sublimated lust, is finally reduced to a tuft of red hair. The setting, too, is narrow, almost amputated. There is, we deduce, a town, with townspeople, but when rains threaten to wash the town away, the sense of emergency seems purely theoretical, and a reader may even be a bit surprised that there is a place in the world Golding has evoked for rain to fall, apart from the roof of the nave. Event is similarly sparse in its rendering. Golding offers barely a hint of the religious activity native to any active cathedral. As the spire rises, we are shown dust, snapshots of progress, but no sweat, a minimum of muscular exertion. All this haunting lacuna prompted one critic to describe the book as “seriously underwritten.”

So, if one is predisposed to dismiss this novel, one need not look far for reason. I found myself unable to do so.

Within the first dozen pages, I believed I had the novel pegged. The consistently taut and beautiful prose notwithstanding, I knew where this story was going and could see no prospect for surprise. Yet, following the trail of those fascinatingly poised and pointed sentences, I kept on, and found that, page by page, the narrative never went where I thought it would, at least not quite, and in the end, not at all. So that months later, needing a brief respite from The Brother’s Karamozov, I opened The Spire again, this time setting aside my reservations and allowing for one of two possibilities:

A. that I might have bad taste and be easily manipulated by heavy handed symbolism and shameless allegory, or

B. that Golding, whatever his limitations, might just have known what he was doing after all.

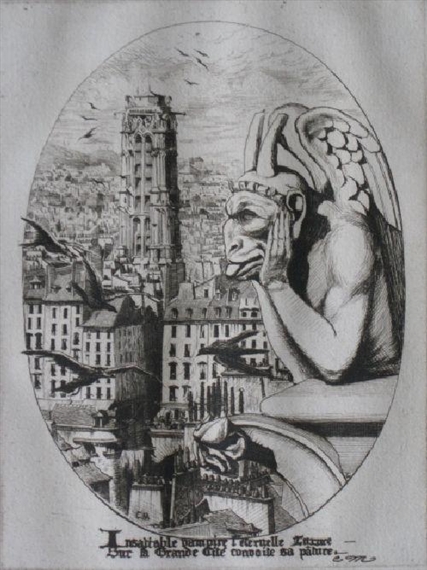

I read with growing fascination as Dean Jocelin’s mania transformed him from a blind narcissist into a gargoyle (quite literally; a craftsman, dumb and smiling, carves his beaky visage to be placed on each of the four corners of the tower), which, in the end, cracks open to reveal a deeply flawed and broken human being. I tried rolling my eyes a little when the rains brought forth the smell of corruption from the open earth at the crossing where the tombs of long forgotten bishops had been disturbed, but found it somehow unsatisfying, as if caught in my own caginess rather than Golding’s. The singing pillars, in spite of their admittedly underlined reference to the fall awaiting the sin of Pride, nonetheless evoked a very real and hypnotic sense of menace. The play of Light (sun bursting through the stained glass windows) and Dark (the pit, human sacrifice) blurred in the cathedral’s dust-laden atmosphere.

In the end, it turned out that I had read, for a second time but as if for the first, a complex novel, not at all “underwritten”, whose final ambiguity enables it to transcend the sum of its frequently allegorical parts. Unlike with a bald faced allegory, such as Lord of the Flies, I emerged from The Spire unsure what to think, wondering just what had happened here, but having been deeply moved.

I don’t frequently reread books. In my next post I will say more about why, this time, I am glad I did.

Have you read The Spire? Any other of Golding’s novels? I would love to hear your thoughts.