I.

A house, a garden,

are not places:

they spin, they come and go.

Their apparitions open

another space

in space,

another time in time.

( from “A Tale of Two Gardens”)

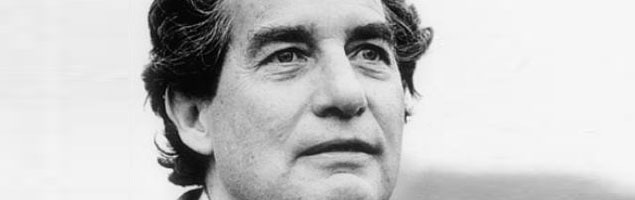

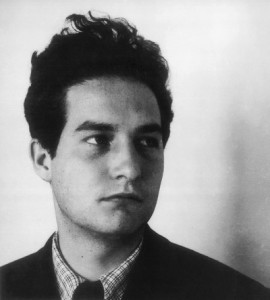

An early indication of Octavio Paz’s affinity for surrealism came when, as a boy, he saw a painting depicting vines winding through the walls of a house, and took it for realism. He would have seen nothing out of the ordinary in such an image. Gardens, he knew, grew junglelike, and walls collapse; he was used to the strangeness of sunlight streaming through collapsed roofs into rooms only recently occupied. Such was part of the regular progression of days living in his grandfather’s house. The old world was passing, taking the house with it.

Such passings had happened before in Mixoac; the village, on the outskirts of Mexico City, had a small Aztec pyramid, a reminder of what was lost when Quetzalcoatl took on the form of Hernán Cortés and returned to Tenochtitlan. The parish church dated from the sixteenth century, a visible reminder of Mexico’s three-centuries as a Spanish colony. Many houses in Mixoac had been standing long before the French invaded, mid-nineteenth century, and set their Austrian rag doll, Maximilian, on the stage-set throne of the Second Mexican Empire. The Paz house, with its crumbling rooms and library of more than six thousand volumes, had been a summer residence purchased by Grandfather Ireneo, trophy of his success as a novelist and journalist loyal to Porfirio Diaz. Diaz, three decades a dictator, progressive to the idea of Mexico, oppressive to Mexicans, his time too had passed. Only late in life, and very late in Diaz’s reign, did Ireneo renounce him for the democratic, but weak, Francisco Madero. By the time Octavio was born, it was Pancho Villa’s time, and Emiliano Zapata’s, the radical revolutionaries.

As one after another of the abandoned rooms turned to rubble, presenting the puzzle of an ever shifting perimeter, he learned what changes, what remains. The arguments, for example, remained. It was The Revolution. Grandfather Ireneo, would go round and round with his son, Octavio Paz Solorzano, who in 1914, the year of his only son’s birth, had become a Zapatista. Battles over the fate of the country, echoing across the Valley of Mexico and beyond, echoed, too, through the ever diminishing rooms of that house in Mixoac. The boy – what could he do then with the dialectic of reform and revolution, of history and myth? – witnessed all in silence. There was, in any case, that library.

II.

there’s nothing in front of me, only a moment

salvaged from a dream tonight of coupled

images dreamed, a moment chiseled

from the dream, torn from the nothing

of this night, lifted by hand, letter

by letter, while time, outside, gallops

away, and pounding at the doors of my soul

is the world with its blood thirsty schedules,

(from “Sunstone”)

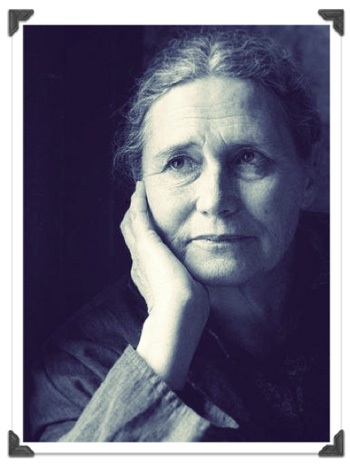

Paz’s career-long study of the Mexican character included regular digressions on the character of the United States. In The Labyrinth of Solitude, his masterpiece, he writes, “North Americans want to understand and we want to contemplate. They are activists and we are quietists; we enjoy our wounds and they enjoy their inventions.” On one level, he is addressing the perennial question of the Latin American intellectual, the problem of the necessarily fraught relationship with the United States. But Paz is a supreme virtuoso of levels, and on another, deeper one, he is talking about two radically different approaches to time: historical time verses mythic time. Chronological verses cyclical, or – a favorite spacial metaphor of his – time as a spiral. It’s a preoccupation so deep with him that, whatever else he may be writing about, he’s probably writing about this. In Labyrinth, he returns frequently to the fiesta as the emblematic cultural gesture of the Mexican people, in which “time is transformed to a mythical past or a total present.” This concept of time is associated with societies of the past, and so called “traditional” societies. It is also associated with childhood. He is often at pains to counter the hegemony of cultures which privilege historical time, with its concomitant notion of “progress”, over mythic time, as in a passage quoted (but unfortunately un-cited) by Nadine Gordimer in her wonderful meditation, “Octavio Paz: Poet-Archer”:

Paz’s career-long study of the Mexican character included regular digressions on the character of the United States. In The Labyrinth of Solitude, his masterpiece, he writes, “North Americans want to understand and we want to contemplate. They are activists and we are quietists; we enjoy our wounds and they enjoy their inventions.” On one level, he is addressing the perennial question of the Latin American intellectual, the problem of the necessarily fraught relationship with the United States. But Paz is a supreme virtuoso of levels, and on another, deeper one, he is talking about two radically different approaches to time: historical time verses mythic time. Chronological verses cyclical, or – a favorite spacial metaphor of his – time as a spiral. It’s a preoccupation so deep with him that, whatever else he may be writing about, he’s probably writing about this. In Labyrinth, he returns frequently to the fiesta as the emblematic cultural gesture of the Mexican people, in which “time is transformed to a mythical past or a total present.” This concept of time is associated with societies of the past, and so called “traditional” societies. It is also associated with childhood. He is often at pains to counter the hegemony of cultures which privilege historical time, with its concomitant notion of “progress”, over mythic time, as in a passage quoted (but unfortunately un-cited) by Nadine Gordimer in her wonderful meditation, “Octavio Paz: Poet-Archer”:

Every time the Europeans and their North American descendants have encountered other cultures and civilizations, they have called them backward. This is not the first time a race or a civilization has imposed its forms on others, but it is certainly the first time one has set up as a universal ideal, not a changeless principle, but change itself. The Muslim or Christian based the alien’s inferiority on a difference of faith: for the Greeks or Toltecs, he was inferior because he was a barbarian, a Chichemecan. Since the eighteenth century, Africans or Asiatics have been inferior because they were not modern. The Western world has identified itself with change and time, and there is no modernity other than that of the West…the new Heathen Dogs can be counted in the millions…they are called ‘underdeveloped peoples’.

This ambiguous notion of modernity needled him early on. As a young man he was determined to become a “modern” poet. But no sooner was the thought formed than the questions arose. What, exactly, is modernity? “There are as many types of modernity as there are societies,” he writes in his Nobel Lecture. “Each society has its own. The word’s meaning is as uncertain and arbitrary as the period that precedes it, the Middle Ages. If we are modern when compared to medieval times, are we perhaps the Middle Ages of a future modernity? Is a name that changes with time a real name?” Modernity was, for him, inextricably tied to the present. But, as awareness of the wider world grew in him – of great events in Europe, of the progress of the United States – he began to feel that Mexico had been separated from the present, that “the present” was “the time lived by others, the English, the French, the Germans. It was the time of New York, Paris, London.” It was to this feeling of expulsion from the present that he attributed his drive to write poetry, for poetry is in love with the instant, dislodges it from sequential time, and fixes it in an eternal present. Poetry lives in mythic time.

This ambiguous notion of modernity needled him early on. As a young man he was determined to become a “modern” poet. But no sooner was the thought formed than the questions arose. What, exactly, is modernity? “There are as many types of modernity as there are societies,” he writes in his Nobel Lecture. “Each society has its own. The word’s meaning is as uncertain and arbitrary as the period that precedes it, the Middle Ages. If we are modern when compared to medieval times, are we perhaps the Middle Ages of a future modernity? Is a name that changes with time a real name?” Modernity was, for him, inextricably tied to the present. But, as awareness of the wider world grew in him – of great events in Europe, of the progress of the United States – he began to feel that Mexico had been separated from the present, that “the present” was “the time lived by others, the English, the French, the Germans. It was the time of New York, Paris, London.” It was to this feeling of expulsion from the present that he attributed his drive to write poetry, for poetry is in love with the instant, dislodges it from sequential time, and fixes it in an eternal present. Poetry lives in mythic time.

III.

The vegetation of disaster

ripens beneath the ground

They are burning

millions of bank notes

in the Bank of Mexico

On corners and in plazas

on the wide pedestals of the public squares

the Fathers of the Civic Church

a silent conclave of puppet buffoons

neither eagles nor jaguars

* * *

We are surrounded

I have gone back to where I began

Did I win or lose?

(You ask

what laws rule “success” and “failure”?

The songs of the fishermen float up

from the unmoving riverbank

Wang Wei to the Prefect Chang

from his cabin on the lake

But I don’t want

an intellectual hermitage

in San Angel or Coyoacán)

All is gain

if all is lost

(from “Return”)

From his position as Mexico’s foremost intellectual, Octavio Paz appraised the hobbled post-Revolution Mexican intelligentsia. The government, eager to legitimize itself, in the eyes of the world and, most especially, its own, enlisted the nation’s poets, novelists, sociologists and philosophers to be aides and advisors to the generals and political bosses. They were assigned to fortify the diplomatic service and the various facets of public administration. Their roll was not, as in Europe or the United States, to discuss public affairs from outside the halls of power where their greatest strength was their critical freedom, but to fulfill their civic duty. In The Labyrinth of Solitude he enumerates the difficulties of their situation:

Many aspects of their work have been admirable, but they have lost their independence and their criticism has become excessively diluted, out of prudence or Machiavellism. The Mexican intelligentsia as a whole has not been able to use the weapons of the intellectual – criticism, examination, judgement – or has not learned how to wield them effectively. As a result, the spirit of accommodation – a natural product, it would appear, of all revolutions that turn into governments – has invaded almost every area of public activity.

This passage (indeed the whole book) is a remarkable achievement. Ilan Stavans has pointed out that he was able to fashion in this book a highly elusive voice, at once an insider’s voice and an outsider’s. He was, himself, enlisted into diplomatic service, first in France, then India, thereby numbering among the very intelligentsia he criticized. Paz, it seems, understood that writing as an outsider made possible the critical distance, but that the discernment this allows has value only in as much as one uses it to scrutinize oneself as an insider. Eighteen years after The Labyrinth of Solitude was published, Tlateloco gave him a chance to embody this voice and give Mexico a new kind of intellectual.

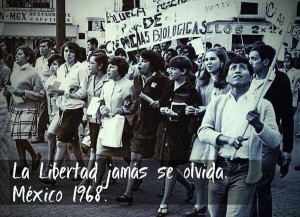

1968 was to be the year of the Mexico City Olympic Games. Around the world, it was also the year of student protests. Prague, Berkeley, Paris. Then, in July, because of a vicious police action against a student disturbance which, until that moment, hadn’t even been political, Mexico City. A protest against the police action was put down by an even more virulent action ordered by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. At the end of July, a small group of leftists met to celebrate the anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. Díaz Ordaz ordered them similarly suppressed. His fear was that such groups were poisoning the minds of the students, threatening the peace which must reign for the Olympic Games that Fall. The situation escalated. Soon all the schools went on strike. The government responded by sending the army to attack them. The problem Díaz Ordaz had, himself, created rocked the nation. On October 2nd over ten thousand college and high school students gathered in Tlateloco’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas to peacefully protest the PRI government’s actions. The army arrived and fired on the crowd, initiating a massacre which continued into the night. The next day, Octavio Paz resigned his post as ambassador to India, a measure of dissent unheard of for a Mexican intellectual. His resignation was applauded worldwide.

1968 was to be the year of the Mexico City Olympic Games. Around the world, it was also the year of student protests. Prague, Berkeley, Paris. Then, in July, because of a vicious police action against a student disturbance which, until that moment, hadn’t even been political, Mexico City. A protest against the police action was put down by an even more virulent action ordered by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. At the end of July, a small group of leftists met to celebrate the anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. Díaz Ordaz ordered them similarly suppressed. His fear was that such groups were poisoning the minds of the students, threatening the peace which must reign for the Olympic Games that Fall. The situation escalated. Soon all the schools went on strike. The government responded by sending the army to attack them. The problem Díaz Ordaz had, himself, created rocked the nation. On October 2nd over ten thousand college and high school students gathered in Tlateloco’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas to peacefully protest the PRI government’s actions. The army arrived and fired on the crowd, initiating a massacre which continued into the night. The next day, Octavio Paz resigned his post as ambassador to India, a measure of dissent unheard of for a Mexican intellectual. His resignation was applauded worldwide.

IV.

Enormous desert and secret fountain

scale of silence and tree of screams

body that unfolds like a sail

body that enfolds like an ember

heart I tear out from the night

scorpion fixed to my chest

seal of blood on my years as a man

(from “Sway”)

My friend Nathan, who translates Spanish literature, texted me recently as part of an ongoing exchange we’ve been having about Paz: “I watched a television debate between Paz and Vargas Llosa the other night,” he wrote. “I don’t know that I’d like to be friends with either. Vargas Llosa seems like that popular kid at school whose overbite is even perfect. They both seemed used to being taken very, very seriously. Or, to put it another way: Paz looked unused to being disagreed with, and Vargas Llosa looked like he’d never agreed with anyone in his life.”

My friend Nathan, who translates Spanish literature, texted me recently as part of an ongoing exchange we’ve been having about Paz: “I watched a television debate between Paz and Vargas Llosa the other night,” he wrote. “I don’t know that I’d like to be friends with either. Vargas Llosa seems like that popular kid at school whose overbite is even perfect. They both seemed used to being taken very, very seriously. Or, to put it another way: Paz looked unused to being disagreed with, and Vargas Llosa looked like he’d never agreed with anyone in his life.”

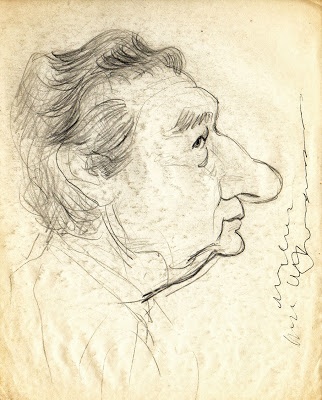

It is well known that later in his life, Paz engaged in quarrels with other writers, especially those ranking alongside him in stature, Mario Vargas Llosa, for example, and the poet José Emilio Pacheco, and, most famously, Carlos Fuentes. Nathan’s observation is astute; in spite of his strongly democratic ideals, his ultimately dictatorial constitution did not easily suffer dissent. Any writer wishing to be published in his highly influential literary magazine, Vuelta, had to, as they say, shine his shoes. Since the 1960s he had been a ruling member of what novelist José Agustín called the Mexican “literary mafia”, and as the years went by the shadow he cast continued to grow. Between 1977 and 1990 he cleaned up on the literary prize circuit, winning the Jerusalem Prize, the Cervantes Prize, the Neustadt Prize, and the Nobel Prize, along with a host of others. He was, incontestably, a national treasure. For this very reason, many felt he had lost touch with the vibrant new antiestablishment artistic trends and saw him as a friend of the status quo. There were even rumors that the Nobel had been a gift from President Salinas, leader of the very PRI party he had condemned with such bitter eloquence after Tlateloco. Ilan Stavans, in his short, brilliant book, Octavio Paz: A Meditation, writes,

Paz’s standing as Mexico’s foremost intellectual was in jeopardy: he was a poet manqué, no longer a valiant Ulysses. For doesn’t the intellectual need autonomy to function? In 1984, on his seventieth birthday, Televisa devoted a series of programs to his work. From that moment on his face appeared regularly on state and private television, and diplomats and academics sought his advice and favor. His home was a required stop for overseas celebrities visiting the country. Yet, in becoming the government’s favorite denizen, he also, in the eyes of many, lost his freedom.

Then, without excusing Paz, Stavans writes, with a levelness and wisdom worthy of Paz at his best, “But aren’t we all blinded by the urgencies of the day? Isn’t the road he followed, from rebellion to consent, a road much traveled?” Gardens grow junglelike, walls collapse. Paz was an indisputable giant. He was also a man.