She insists, that flinty Elizabeth Bishop, that “the art,” (how coy) “of losing isn’t hard to master.” She presumably would know. Considering my response over the weekend to this blog going apparently missing, I’m clearly a slow study. I believe I was somewhat less infantile than I was on my fortieth birthday when I gave myself whiplash by looking rather too sharply over my shoulder at what I believed to be my years of hope and possibility streaming away from me, but I was in no sense composed. Put yourself in my suspenders: On Friday night, when I attempted to visit my two-year-old plot of cyber-acreage which I had named, quite wittily I thought, “The Stockholm Shelf”, I found my access blocked by an image of a smiling blonde female student, as intransigent as she was impertinent, presiding over a list of Stockholm-related links: Stockholm restaurants, Stockholm hotels, Stockholm furniture, Stockholm garden hoses, as well as a few items only identifiable in Swedish. I can mark the absurd, and even sometimes laugh at it, on two conditions, that it not be violent, and that it not affect me personally. Irrational, I know, but the latter always feels like the former. That is to say, Ms. Bishop, “like disaster.”

Thankfully, the problem was only a glitch in my web host’s system which prevented it from acknowledging the renewal of my contract. The woman who caught my wailing at the receiving end of the help-line, whom I couldn’t help picturing of an age with that insipid blonde girl barring my path, barely suppressed her own sigh of dismay to explain that they had received exactly the same complaint numerous times over the past week and that the one technician able to fix the problem would apply himself to my site as soon as he could get to it. When on Monday I checked for the four-hundredth time, and the blonde girl was gone, and the reassuring layout of my WordPress dashboard met met my gaze with the equivalent of a raised brow, as if wondering where I had been, I nearly cried.

It put me in mind of Hemingway and his lost valise. No help-line to call, no contending with dumb technology, although there was a girl involved, all those months and years of hard creative labor, the efforts to invent himself, gone, all at once, simply. Although – and here’s the absurd part – it wasn’t really gone. Someone had it. At least for awhile.

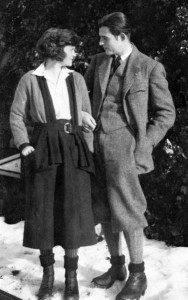

The story goes that in December of 1922, while living in Paris and working as a correspondent for The Toronto Daily Star, Ernest Hemingway was placed on assignment in Switzerland to cover the Lausanne Peace Conference. While he had, by then, written some twenty four stories, twenty poems, and had a novel, probably A Farewell to Arms, well underway, he had not published a word of it. At the conference, he became reacquainted with a journalist and editor by the name of Lincoln Stevens, whom he had met once before in Genoa, Italy. Stevens was suitably impressed by Ernest’s writing and asked to see more. To this end, his wife, Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (his first, though at the time there was no intimation that she would eventually be so designated), who had stayed behind in their flat in Le Quartier Latin, packed up her husband’s writing, all of it, in a suitcase and and set out to meet him in Lausanne. At some point, while the Swiss-bound train sat, hissing and massive, in the Gare de Lyon in Paris, Hadley, as she was called, and the valise parted ways. Whether she had handed it to a porter or simply left it unattended, when she returned to her cabin, it was gone, together, I would imagine, with the contents of her bladder, or very nearly.

The leading theory is that it was stolen. One feels for the thief. Imagine taking the trouble to swipe a valise, thinking it contained valuables, and finding it contained only sheafs of paper, scrawled and typed on. All that risk for a bulky item that then just needed to be disposed of, burned, buried, stashed, or perhaps thrown into the Seine. Once accomplished, the poor fellow would have faced whatever fortune remained to his days, never understanding that, if he had simply held on to the thing for a scant thirty two years, he would have had in his possession a treasure of inestimably greater value than whatever his most far-flung imaginings could have placed in that unprepossessing suitcase. To have in your hands even one Hemingway manuscript, and not to know it was a Hemingway manuscript, or what that would mean one day not too distant, and to let it go, it puts me in mind of Pablo Neruda’s prediction of the fate awaiting someone who has never read Julio Cortazar, the lack acting upon him as “a serious invisible disease which in time can have terrible consequences. Something similar to a man who has never tasted peaches. He would quietly become sadder… and, probably, little by little, he would lose his hair.”

To say nothing of how it affected Ernest Hemingway. He himself could not have known at the time what losing a Hemingway manuscript would one day mean, or not the extent of it. But he knew what it meant to him at the time, and something, no doubt, of what he hoped it would, or could, mean to the world, and somehow, despite all his efforts to think otherwise, Hadley wasn’t quite as pretty as she had been in November.

In January 1923, Hemingway confided to Ezra Pound in a letter: “I suppose you heard about the loss of my Juvenalia (Hemingway’s misspelling)? Went up to Paris last week to see what was left and found that Hadley had made the job complete by including all carbons, duplicates, etc. All that remains of my complete works are three pencil drafts of a bum poem which was later scrapped, some correspondence between John McClure and me, and some journalistic carbons. You, naturally, would say, ‘Good’ etc. But don’t say it to me. I ain’t yet reached that mood.”

Not quite true that it was all that remained of his complete works. Two stories survived the disaster: “My Old Man,” which was actually in the hands of a magazine editor at the time, and “Up In Michigan”, which he had buried in a drawer after Gertrude Stein declared it good but, with its disturbing sexual content, inaccrochable.

Yes, you read correctly. “Inaccrochable.”

Pound’s response was that all he had actually lost was the time it would take to rewrite the pieces anyway. Hemingway rallied, and by 1925 had produced In Our Time, the book of stories that introduced the world to what would soon be, and forever after, known as the “Hemingway style”.

Many years later, with a Nobel Prize behind him, Hemingway recalled the loss of his early manuscripts. “It was probably a good thing it was lost,” he wrote in A Moveable Feast, “When I had written a novel before, the one that had been lost in the bag stolen at the Gare de Lyon, I still had the lyric facility of boyhood that was as perishable and deceptive as youth was.” Here, then, is a great writer’s take on loss, that after it shakes one where one lives, after the dust settles, after the ruins are assessed, it is revealed as a fundamentally ambivalent beast. The nerve endings heal or habituate, the scars are for keeps, and something that may not have been otherwise possible can come forth and change everything. In order for Hemingway to become what he was, it was most important for him to loose what he wasn’t.

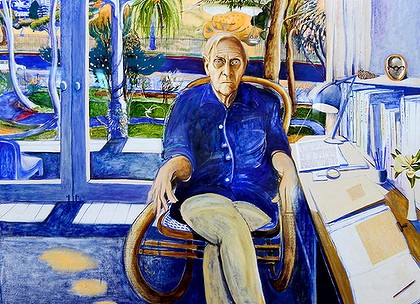

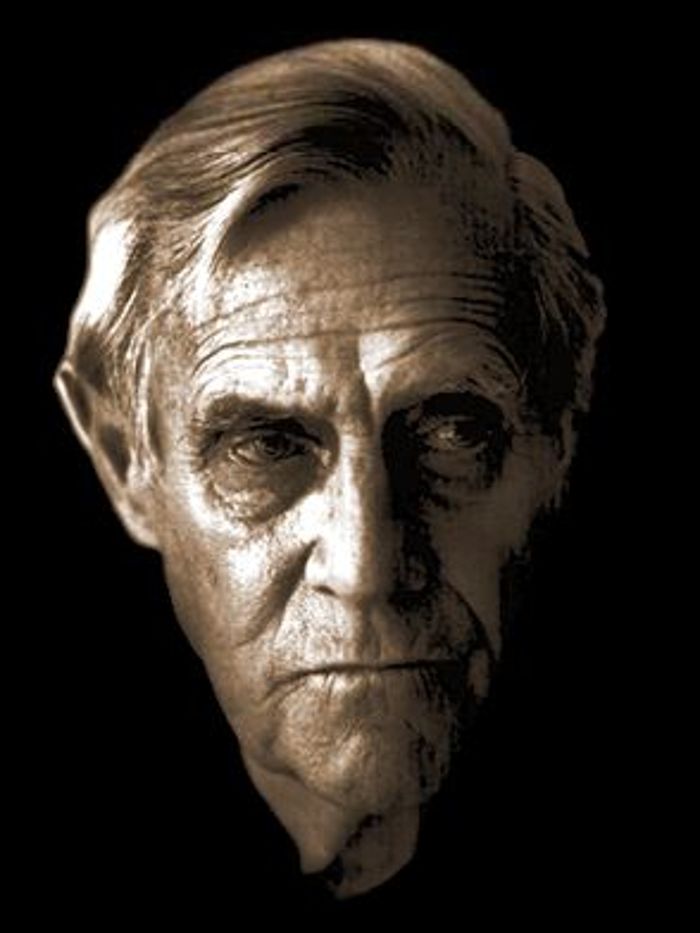

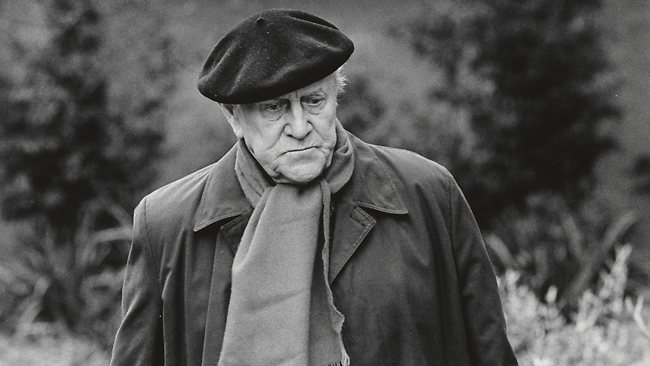

The teapot tempest of my three-days-missing blog put me in mind of Hemingway’s lost valise. It then occurred to me that, while Hemingway is a fine writer, he’s not so special as to be the only fine writer to have lost irreplaceable work. I had forgotten, for example, that Toni Morrison’s house burned down on Christmas Day, 1993, just three weeks after her trip to Stockholm. A little web-surfing turned up others among the Nobel laureates who had sustained similar losses. Pearl Buck, Tagore, Soltzhenitsyn, each experienced manuscripts gone missing. In upcoming posts, I’ll share their stories.