In repressive regimes everywhere – whether in what was the Soviet block, Latin America, Africa, China – most imprisoned writers have been shut away for their activities as citizens striving for liberation against the oppression of the general society to which they belong. Others have been condemned by repressive regimes for serving society by writing as well as they can; for this aesthetic venture of ours becomes subversive when the shameful secrets of our times are explored deeply, with the artist’s rebellious integrity to the state of being manifest in life around her or him; then the writer’s themes and characters inevitably are formed by the pressures and distortions of that society as the life of the fisherman is determined by the power of the sea.

– from the Nobel Lecture: “Writing and Being”

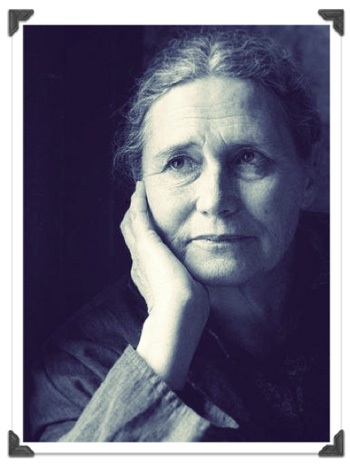

In an autobiographical essay published in the New Yorker in 1954, Nadine Gordimer described a hill rising from the veld on the outskirts of her home town near Johannesburg, barren save for patches of sparse grass through which showed a blackness “even a little blueness, the way black hair shines”. The hill was a coal dump, so old as to be covered by a layer of blown earth. “Diabolical”, she called it, “forsaken”, and – her best word – “inert”, for at some point, no one knew when, this remnant of a long abandoned coal mine had caught fire, and the slow, low burning had continued, hidden beneath its top layers, day and night, for many years. She recalled the surrounding earth feeling warm beneath her feet. She remembered seeing the glow at dusk in the bald patches where grass would not grow. She knew a girl who had been horribly disfigured from burns sustained while playing on the hill. Her mother remembered a boy who had been buried in a landslide and not even his bones had been found. On one side of the coal dump was the outer edge of town, the “location”, where the blacks lived. Further from the dump, in the direction of the town center, were the neighborhoods of what she described as “our sedate little colonial tribe, with its ritual tea parties and tennis parties.” On the other side was the local nursing home which served also as a hospital and clinic, where her mother spent many long days.

It’s a striking image, this smoldering hill, though susceptible to portentousness. Even a very good writer of lesser gifts might have worried it toward the gothic. Gordimer doesn’t interfere with it, pretending there is nothing deliberate about it’s inclusion in her narrative, calling it no more than a memory, one among many which occurred to her in the course of writing. Attuned, as she writes in her Nobel lecture, “to the state of being manifest in life around her”, she knows this Hades-like image is organic to her theme and will pay its own way. The title of the essay is “A South African Childhood: Allusions in a Landscape”. A reader with even cursory awareness knows full well what that mountain of hidden burning alludes to —in South Africa.

When she wrote this, the great novels, The Conservationist, Burger’s Daughter, July’s People, A Sport of Nature, were still to come.

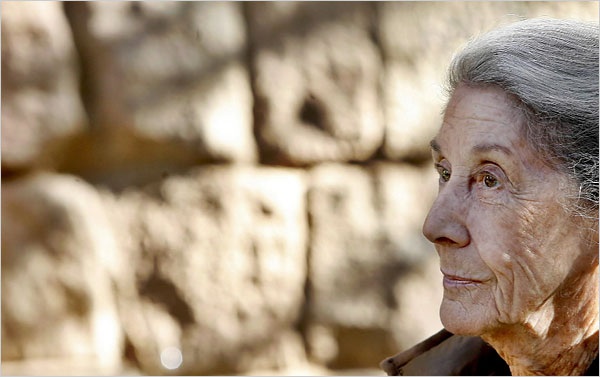

While the tributes which have flooded the internet and news publications in the past two weeks all get around to acknowledging what a towering writer she was, it was her activism that tends to make the headlines and to frame whatever else is said of her. The value claimed for her novels and stories, as good as they are, is largely extra-literary. She is routinely revered as a kind of warrior writer who courageously laid bare the viciousness of apartheid. Arguably the highest compliment she was ever paid came from the South African government, years before the Nobel, when it banned three of her books. It is put forth as as a testament to her greatness that she was one of the first people Nelson Mandela wanted to see upon release from prison. “But she was a writer first,” the articles protest, then back up what should be self-evident with examples of her post-apartheid subject matter and her vigorous contribution to the fight against HIV/AIDS in Africa. With intentions to the contrary, her life often comes off sounding like a kind of bourgeois parable illustrating that one can still find fulfillment in life’s third act, even after everything has changed. Imagine Samuel Beckett requiring such a defense.

While the tributes which have flooded the internet and news publications in the past two weeks all get around to acknowledging what a towering writer she was, it was her activism that tends to make the headlines and to frame whatever else is said of her. The value claimed for her novels and stories, as good as they are, is largely extra-literary. She is routinely revered as a kind of warrior writer who courageously laid bare the viciousness of apartheid. Arguably the highest compliment she was ever paid came from the South African government, years before the Nobel, when it banned three of her books. It is put forth as as a testament to her greatness that she was one of the first people Nelson Mandela wanted to see upon release from prison. “But she was a writer first,” the articles protest, then back up what should be self-evident with examples of her post-apartheid subject matter and her vigorous contribution to the fight against HIV/AIDS in Africa. With intentions to the contrary, her life often comes off sounding like a kind of bourgeois parable illustrating that one can still find fulfillment in life’s third act, even after everything has changed. Imagine Samuel Beckett requiring such a defense.

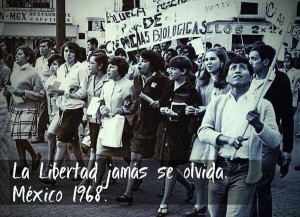

Susan Sontag issued a corrective to this view of her in 2004 in the inaugural Nadine Gordimer Lecture, the last speech she ever gave: “But of course, the primary task of a writer is to write well (And to go on writing well. Neither to burn out nor to sell out.) In the end — that is to say, from the point of view of literature — Nadine Gordimer is not representative of anybody or anything but herself. That, and the noble cause of literature. Let the dedicated activist never overshadow the dedicated servant of literature — the matchless storyteller.” In a kind of relay race among literary insiders, Sontag took her declaration that a writer’s primary task is to write well from Gordimer’s Nobel lecture in which she, in turn attributed to Gabriel Garcia Marquez the belief that “The best way a writer can serve a revolution is to write as well as he can.” (His actual words, spoken to a journalist friend, were “In reality the duty of a writer — the revolutionary duty, if you like — is that of writing well.” The implication of each is slightly different, but holds to the idea that writing is a moral act.)

Susan Sontag issued a corrective to this view of her in 2004 in the inaugural Nadine Gordimer Lecture, the last speech she ever gave: “But of course, the primary task of a writer is to write well (And to go on writing well. Neither to burn out nor to sell out.) In the end — that is to say, from the point of view of literature — Nadine Gordimer is not representative of anybody or anything but herself. That, and the noble cause of literature. Let the dedicated activist never overshadow the dedicated servant of literature — the matchless storyteller.” In a kind of relay race among literary insiders, Sontag took her declaration that a writer’s primary task is to write well from Gordimer’s Nobel lecture in which she, in turn attributed to Gabriel Garcia Marquez the belief that “The best way a writer can serve a revolution is to write as well as he can.” (His actual words, spoken to a journalist friend, were “In reality the duty of a writer — the revolutionary duty, if you like — is that of writing well.” The implication of each is slightly different, but holds to the idea that writing is a moral act.)

A great writer is like a thief, stealing from the treasury of the world’s wordless and recondite state of being more meaning for her words than is their legal due. Among living writers, Alice Munro is one of the most light-fingered, stashing more significance into the hidden pockets of her pokerfaced sentences than most writers acquire by honest means in the space of a paragraph. Gordimer was like this. She was more cerebral by half than Munro. She was more at home with artifice – Toni Morrison is a closer relative in this regard – taking occasional well-judged flights from realism. For example, Munro would never write a story in the form of an answer to Franz Kafka’s famous “Letter to His Father” from the father himself, one deceased to another. Nor would she gather Susan Sontag, Edward Said, and Anthony Sampson, all of them dead, for colloquy at a Chinese restaurant. But like Munro she could smuggle a mother lode of emotional impact and intellectual weight right under her readers’ noses and deposit her hoard on the page. Listen to how she packs away a startling wealth into this unassuming description of a two-room township house in her story “A City of the Dead, A City of the Living”:

The front door of the house itself opens into a room that has been subdivided by greenish brocade curtains whose colour had faded and embossed pattern worn off before they were discarded in another kind of house.

First off, a subdivided room was, by definition, once whole. That someone decided on this make-do solution makes the brocade curtains a comedown even before we learn they are faded and worn. They’re not green, mind you, but “greenish”. Of course they are second hand, who would do this with something nice? But it’s that ending, “discarded in another kind of house”, that makes you realize what she’s pulled on you after its far too late to man your defenses. What kind of house? The least that can be said is that it was one in which brocade curtains could be discarded. Like the smoldering coal dump haunting the edges of her childhood, the almost off-handed pitting of a township house with its second-hand dividing curtains against “another kind of house”, without ever mentioning the dynamics between blacks and whites in a society hideously deformed by apartheid, lends an emotional impact anything more explicit would subvert. In the span of a phrase, it becomes that kind of story.

A sentence like this functions as a hologram, not only of the story itself, but, of the mind of it’s writer. Gordimer thought more, and more complexly, about the world she observed than most of us could ever hope to. But, as can happen with genius, the complexity of her mind occasionally ran away with her capacity to make it’s products syntactically approachable. In this passage from her meditation on the craft of writing, “The Dwelling Place of Words” (2001), we hear her thoughts chasing each other into a logjam of a sentence:

And in the increasing interconsciousness, the realization that what happens somewhere in the world is just one manifestation of what is happening subliminally or going to happen in one way or another, affect in one way or another, everywhere – the epic of emigration, immigration, the world-wandering of new refugees and exiles, political and economic, for example – is a fatal linkage, not ‘fatal’ in the deathly sense, but in that of inescapable awareness in the writer.

It all makes perfect sense on about the third pass. All clauses are resolved, all modifiers firmly attached, indeed all the requirements of an English sentence are fulfilled, but the reader has nonetheless endured a moment of terror, sure he’s made a fatal turn in the labyrinth and will not escape. But what the reader gets, even on a first pass, is a kind of urgency, an imperative that he be given a full account of what is important. We hear the shameful secrets of the times, the pressures and distortions of society weighing on her moral sensibility, and there is so much to say about it. If she could stack the words on top of each other she would.

In 2006 a biography came out which purported to tell the truth about Nadine Gordimer. It was a biography she had authorized. And then rescinded, going so far as to block its US release. The hypocrisy of a white liberal woman, her unconscious racism, an affair – these were some of its haul, confiscated, supposedly, from the iconic status of its subject. Among the biographer’s claims was that certain elements of the essay “A South African Childhood” had been fabricated. And so a seed of doubt is planted: is the subterranean smolder of the coal dump in a land on the edge of igniting factual, or a storyteller’s invention? And, more at issue, is this important? It seems to me that serious readers, by this late date, are grown up enough to know better than to troll autobiography for facts. What kind of reader would turn to, say, Garcia Marquez, for a balanced reckoning? This does not evade the question. Only, how one feels about the answer, disillusioned, vindicated, or more or less unaffected, will depend on what one is reading for, news about the horse from the horse’s mouth, or a brilliant and complex woman’s passionate engagement with her subject and it’s telling.

In 2006 a biography came out which purported to tell the truth about Nadine Gordimer. It was a biography she had authorized. And then rescinded, going so far as to block its US release. The hypocrisy of a white liberal woman, her unconscious racism, an affair – these were some of its haul, confiscated, supposedly, from the iconic status of its subject. Among the biographer’s claims was that certain elements of the essay “A South African Childhood” had been fabricated. And so a seed of doubt is planted: is the subterranean smolder of the coal dump in a land on the edge of igniting factual, or a storyteller’s invention? And, more at issue, is this important? It seems to me that serious readers, by this late date, are grown up enough to know better than to troll autobiography for facts. What kind of reader would turn to, say, Garcia Marquez, for a balanced reckoning? This does not evade the question. Only, how one feels about the answer, disillusioned, vindicated, or more or less unaffected, will depend on what one is reading for, news about the horse from the horse’s mouth, or a brilliant and complex woman’s passionate engagement with her subject and it’s telling.