I sometimes dream of situations that can’t possibly come true. I audaciously imagine, for example, that I get a chance to chat with the Ecclesiastes, the author of that moving lament on the vanity of all human endeavors. I would bow very deeply before him, because he is, after all, one of the greatest poets, for me at least. That done, I would grab his hand. “‘There’s nothing new under the sun’: that’s what you wrote, Ecclesiastes. But you yourself were born new under the sun. And the poem you created is also new under the sun, since no one wrote it down before you. And all your readers are also new under the sun, since those who lived before you couldn’t read your poem. And that cypress that you’re sitting under hasn’t been growing since the dawn of time. It came into being by way of another cypress similar to yours, but not exactly the same. And Ecclesiastes, I’d also like to ask you what new thing under the sun you’re planning to work on now? A further supplement to the thoughts you’ve already expressed? Or maybe you’re tempted to contradict some of them now? In your earlier work you mentioned joy – so what if it’s fleeting? So maybe your new-under-the-sun poem will be about joy? Have you taken notes yet, do you have drafts? I doubt you’ll say, ‘I’ve written everything down, I’ve got nothing left to add.’ There’s no poet in the world who can say this, least of all a great poet like yourself.”

from “The Poet and The World”: Nobel Lecture

And, you, Ms. Szymborska, you too were new under the sun. A hard time you had of it, making your entrance as you did in a time and country when being under the sun was a wretched place to be at all, let alone be new. Poland at the beginning of the 20th century’s ungodly third decade: Hitler was the world’s gift to you at sixteen, with Stalin pawing the earth and snorting at his flanks. After the first set of horrors, you thought communism might mitigate a second. How many like you, young and good, reached ardently for the communist trophy only to find yourselves holding the ball, then the rotten potato, then the turd? No wonder irony was your metier. Rilke warned his young poet off irony lest it master him, but you became irony’s master. You had to: Avoid deportation and forced labor at the hand of the Nazi’s only to have your first book of poems refused publication for being “insufficiently socialist”. A blow, no doubt. Ironic. Necessary. But a blow all the same. And it taught you to sucker-punch like no other poet I know, save, maybe Emily Dickenson.

But, the cost. Could this be why you published comparatively little during your life, the fear that what you wrote would be insufficiently…something? Your compatriot, Czeslaw Milosz, lamented poetry’s insufficiency in the face of life, event, catastrophe. Not that you need to explain yourself on this count. Small outputs are by no means unheard of among great poets. Take the Northern gentleman who just joined you on Stockholm’s roster. His published works number far less than yours, and his greatness, like yours, vaporizes all contest. It must be an American thing, this fussing with amounts. I imagine that mineral-level wickedness which so often lit your face in photographs crackling in your voice when you answered the interviewer who asked you why your output is small, “I have a trash can at home.” Oh did you, then, Ms. Szymborska? Which of us addicts of your funny, pointy, waste-laying poems wouldn’t have loved to rustle through your garbage like junkies after needles?

The obituaries tell us that you had no children. We’d all happily invoke a chestnut, on your behalf, about poets and their poems. But were you aware of the others? Us, I mean. Your readers. We who pressed our minds and hearts against your astonished and astonishing lines, fed on what we found there and grew. We whom you raised to think carefully about things we had barely guessed were there for the thinking; how a beetle, dead on the road, is an opportunity not to be missed for assessing death itself and our inflated sense of importance; how wind blowing from a tree all its leaves but one can teach us about the grim absurdity of violence which can devastate a century, and of which we are, each of us, capable. There have been so many of us. One, Mark Doty, an American poet (you’d have liked him, I think), said of your wrenching poem “Photograph from September 11”, “The genius of Szymborska’s poem lies in its admission that the poet has very little power—and its acknowledgment that she will herein exercise every bit of the power she does have.” Like any good parent, you taught us by example. You were an excellent, if sometimes hard, mother to us. You made us laugh, until we balked in protest. Even Milosz rebelled against your poem “View with a Grain of Sand”, in which you pit inchoate nature against human language to language’s cost, saying “Personally, I think that she is too scientific and that we are not so separated from things.” With all reverence for Mr. Milosz, I think your flintiness tripped him here, so that he got it backwards; your poem speaks of our connection to all things, never mind that the ego and all the rest of the human edifice must go for it to be perceived. Hard. Let’s say it. You were very hard. But, again, such was the time you had of it.

And now you are gone.

It’s been and gone.

It’s been, so it’s gone.

In the same irreversible order,

for such is the rule of this foregone game.

A trite conclusion, not worth writing

if it weren’t an unquestionable fact,

a fact for ever and ever,

for the whole cosmos, as it is and will be,

that something really was

until it was gone,

even the fact

that today you had a side of fries.

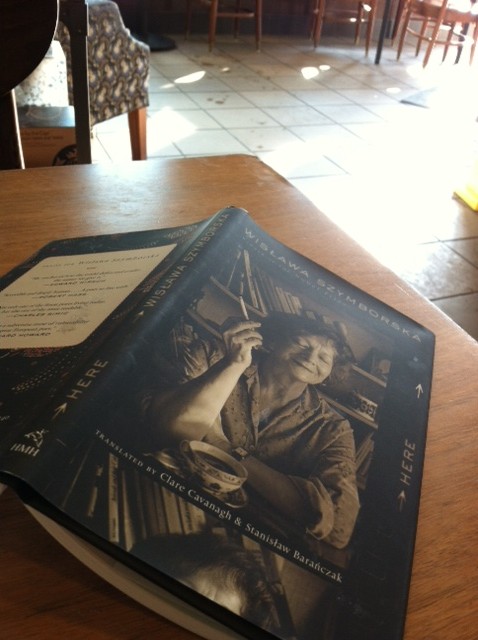

I found this poem, “Metaphysics”, in Here, the last volume of your poetry to be published in English before your death. For all the weight you lay on this poem’s slim shoulders – life’s damned transience, the nature of existence itself – the question this poem raised for me, and which I could neither answer nor shake, was this: Did you, Ms. Szymborska, ever have a side of fries?

And who, dear woman, was the last to bring you flowers during your life? My partner, Sam, had a fantasy of one day traveling to Krakow, finding your address, buying an enormous bouquet and laying it at your doorstep with an unsigned card reading, “And you, Ms. Szymborska, you too were new under the sun,” followed by, “Thank you.” It was the kind of fantasy which never had any probability of being carried out, but as long as you were alive, it was a pleasure to mentally rehearse it from time to time. Now you are gone, and we find this, too, very new.

Thank you for the poems. Thank you…

thanks for this memoriam for ms szymborska.

Hi Maxim!

I’m so pleased you stopped by for a few moments to read my post. I’ve loved our brief exchanges on shelfari and now its an honor to see your name here. Szymborska was such a marvelous poet and I want as many people to know about her as possible. Do you read much poetry? Are you acquainted with Ms. Szymborska’s work?

I enjoyed Wislawa’s Nobel lecture especailly the way she described poets as “fortune’s darlings” It is amazing that this woman, so cosmopolitan and worldly lived behind the iron curtain during the cold war years, and yet could write as she did. I was in Krakow in the late 80’s and the people were still very culturally sequestered, and I’d venture to say that Wislawa never had an order of french fries. Wislawa is never in your face, her irony and humor are tempered and rather subtle. Incidenally, for a woman of a certain age, she was a good looker.

I am smiling at the wonderful thought of Ms. Szymborska being confronted with the fact of her own beauty. Fabulous that you find her a “looker”. The going notion is that those who look well are not notable for looking good.

You were in Krakow! Some people… Ah, well, perhaps someday.