Greece is crumbling. Papandreou has called for a referendum on the the EU’s bailout agreement, blazing a trail towards a European abyss. Now the EU is waiting to excise the sun-drenched country like a melanoma. In Athens, friendly young couples pickpocket helpful old men of their last euros. Once-thriving neighborhoods are now scarred with graffiti and patrolled by prostitutes from Africa.* The exportable stereotype of the Greek male as a swarthy open-shirted devil seducing blond tourists has been supplanted by that of the spoiled, tax-evading professional throwing a tantrum over not being able to retire at fifty. Fifty also being the percentage rise in suicide.** Having scraped and clawed and bled their way up through a century of misery to a tenuous, teeth-gritted prosperity, its all falling down around their ears like a film of the Parthenon time-lapsed at one frame per century. You weren’t going to forget, were you, amidst all the news of plummeting stock markets and mounting chaos, that today marks the 100th birthday of Odysseus Elytis?

Haven’t heard of him? It seems you’re not alone. Greek literature, to most non-Greeks, means Homer or Aeschylus. With a little prompting, the non-Hellenic reader may get a patchy, long-stashed image of Anthony Quinn dancing on the seashore and come up with Nikos Kazantzakis. If you read poetry, you may be lucky enough to have become, along with Auden, an admirer of Constantine Cavafy, whose elevated verse articulated a profound longing for historic Greece through his fascination with beautiful young men. But mention Yannis Ritsos, Angelos Sikelianos, Giorgios Seferis, or Odysseus Elytis, and most people will give a blank stare.

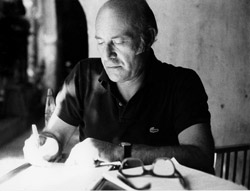

Greece, on the other hand – the Greece of its own better Angel’s, brave and tenacious fighters for independence, raki-drinking street-dancers with long memories of oracles ringing in their ears, home to one of the world’s oldest and greatest literary traditions – Greece holds its poets close with pride. And among them, perhaps Odysseus Elytis most of all. Long before he won the Nobel Prize in 1979, this intensely private man who lived for half a century in the same small apartment in Athens, harnessing French surrealism to the chariot of Helios, was venerated as one of the Immortals.***

In a previous post I referred to Elytis as “tragic-eyed”, at best a misleading epithet, for his poetry is intense, optimistic, and frankly erotic. Listen to this fragment from his early collection, Sun the First:

I lived the beloved name

In the shade of the grandmother olive tree

In the roar of the lifelong sea.

Those who stoned me live no longer

With their stones I built a fountain

Verdant girls come to its threshold

Their lips are descended from the dawn

Their hair unwinds deeply in the future.

In Greece, 2011 has been officially declared the Year of Elytis. Readings, symposiums, installations of his art, and concerts of music inspired by his poetry have been going on for months and will continue through November. As unstable as Greece’s future is, it seems a small point of hope that it remains poet-honoring in this way. Imagine America declaring this the “Year of Elizabeth Bishop”.

In a post later this month I will give you Elytis’s famous poem The Mad Pomegranate Tree. But for now, I leave you with this: A line of poetry by Elytis is currently on display in the Athens metro: “Take a leap faster than decay.”****

*http://www.foreignpolicy.com/greece_financial_crisis_an_elegy?page=0,0

**http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904199404576538261061694524.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTTopStories

***The Collected Poems of Odysseus Elytis, Revised and Expanded Edition, Trans. by Jeffrey Carson and Nikos Sarris, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (2004), p. xxxix.

****http://insidegreece.wordpress.com/2011/05/10/greeces-lost-soul/

As usual, your post is tremendous!

Look how it looks:

Greece is crumbling.

Those who stoned me live no longer

With their stones I built a fountain

Verdant girls come to its threshold

Their lips are descended from the dawn

Their hair unwinds deeply in the future.

But first of all I would check my version for translation differences, if any.

– Madhav

Your appreciation honors me, Madhav.

The translation I used here is from THE COLLECTED POEMS OF ODYSSEUS ELYTIS, translated by Jeffrey Carson and Nikos Sarris. I have mislaid my copy of ODYSSEUS ELYTIS: SELECTED POEMS, translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, but I found their translation of this poem on line. Here is their version of the same lines:

I lived the beloved name

In the shade of the aged olive tree

In the roaring of the lifelong sea

Those who stoned me live no longer

With their stones I built a fountain

To its brink green girls come

Their lips descend from the dawn

Their hair unwinds far into the future

What do you think? The last two lines especially seem to suggest different interpretations: “are descended” carries, for me, the possible implication of an inheritance, whereas “descend” leaves the line simply – if evocatively – descriptive. And what about that unwinding hair? Saying it does so “deeply in the future” leaves the line beguilingly ambiguous: “deeply” points either to the quality of the unwinding or to the temporal distance spanned by the unwound hair, or to the unspecified point in time when the unwinding will occur. Whereas to say it unwinds “far into the future” makes the image clearer, more specifically about duration. Its beautiful either way. I personally like the play allowed by the more ambiguous rendering. I would love to hear your thoughts on this.

I am sorry I am visiting after such a long time and it’s my loss.

Yes, I have ODYSSEUS ELYTIS: SELECTED POEMS: 1940 – 1979, chosen and introduced by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard.

And I also prefer the ambiguous rendering. But,

Their lips descend from the dawn

Their hair unwinds far into the future.

sounds more like a chant and imparts a buoyancy that renders the body/lips/hair less substantial.

Yes, I love both the versions. Can you post the full poem?

I am getting an idea that reading two or more good translations may be a very good idea – in fact it may be a big compensation for missing the original flavour. I am definitely going to give it a try with some other poems in English/Hindi/Bengali.

Here, madhav, is the complete poem “I Lived the beloved name” as translated by Jeffrey Carson and Nikos Sarris:

I lived the beloved name

In the shade of the grandmother olive tree

In the roar of the lifelong sea.

Those who stoned me live no longer

With their stones I built a fountain

Verdant girls come to its threshhold

Their lips are descended from the dawn

Their hair unwinds deeply in the future.

Swallows come infants of the wind

They drink and fly that life go on

The bogey of dream becomes a dream

Grief rounds the good cape

No voice gets wasted in the sky’s bosom.

O unwithering sea tell me what you are whispering

Early on I am in your morning mouth

On the peak where your love appears

I see night’s volition pour forth the stars

Day’s volition lop off the tops of earth.

In the fields of life I sow a thousand campion

A thousand children amid the honest wind

Beautiful strong children from whom goodness mists

Who know to gaze hard at far horizons

When music lifts the islands.

I carved the beloved name

In the shade of the grandmother olive tree

In the roar of the lifelong sea.

I hope this is of interest to you. I don’t pretend to know what all of it means, but it has a beautiful music and I try to trust my personal response to it. I agree with you, reading more than one translation can be very enlightening. The subject of translation is endlessly fascinating.