This week I had intended to publish the follow-up to my last post, about Derek Walcott. But Holy Week has been its usual drama queen self, and no matter how I try to air out my religious sensibility, I’m always brought to my knees by its rapturous tragedy. Consequently, another poet has been knocking about in my skull, clamoring to be heard: the lyrical and tragic-eyed Odysseus Elytis. So, Walcott can wait another week.

For some reason, I always associate Easter with Greece. I love to prepare Greek food for the feast. Two years ago, I made an enormous lamb pie baked in a crust of Greek bread (We ate it all week. Making moderate amounts is difficult for me). Sam makes tzoureki, a Greek braided bread, not unlike Jewish challa, with red-painted Easter eggs baked into the pleats.

This year, Easter dinner will be, not Greek, but Italian, featuring a rustico casserole of cubed lamb tossed with herbs, garlic, tomatoes and Parmigiano-Reggiano, layered with thinly sliced new potatoes. I probably won’t be able to resist trading out the third cup of water the recipe calls for to be added before putting it into the oven with with wine. As crusty as the potatoes will get, and as meltingly tender the lamb, Elytis, in spirit, is scowling at these plans. What his country suffered at the hands of the Italians during World War II, the humiliation of foreign occupation, mass killings, rapes and starvation, would likely cause my cooking this year to catch in his throat. His experience as an officer in the heroic Albanian Campaign that resisted the Italian invasion of Greece became the genesis of the poem that marked the turning point in his career: Heroic and Elegiac Song for the Lost Second Lieutenant of the Albanian Campaign (1945). In a letter to the translator Kimon Friar, Elytis wrote of its origins:

‘A kind of “metaphysical modesty” dominated me. The virtues I found embodied and living in my comrades formed in synthesis a brave young man of heroic stature, one whom I saw in every period of our history. They had killed him a thousand times, and a thousand times he had sprung up again, breathing and alive. His was no doubt the measure and worth of our civilization, compounded of his love not of death but of life. It was with his love of Freedom that he recreated life out of the stuff of death.”

And so he wrote this magnificent cycle, fourteen stanzas, in honor of this imagined, composite, fallen soldier. Without a trace of club-footed allegory, Elytis produced one of the most evocative Easter poems I know. Here is the final stanza in Friar’s translation.

Now the dream in the blood throbs more swiftly

The truest moment of the world rings out:

Liberty,

Greeks show the way in the darkness:

LIBERTY

For you the eyes of the sun shall fill with tears of joy.

Rainbow-beaten shores fall into the water

Ships with open-sails voyage on the meadows

The most innocent girls

Run naked in men’s eyes

And modesty shouts from behind the hedge

Boys! There is no other earth more beautiful

The truest moment of the world rings out!

With a morning stride on the growing grass

He is continually ascending;

Around him those passions glow that once

Were lost in the solitude of sin;

Passions flame up, the neighbours of his heart;

Birds greet him, they seem to him his companions

‘Birds, my dear birds, this is where death ends!’

‘Comrades, my dear comrades, this is where life begins!’

The dew of heavenly beauty glistens in his hair.

Bells of crystal are ringing far away

Tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow: the Easter of God!

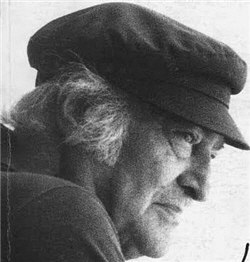

Odysseus Elytis, made a Nobel Laureate in 1979, died in 1996. This year, he would have turned one hundred. Many regard him as the greatest Greek poet of the 20th century. Greece is making a great fuss over him this year, and as his birthday, November 2, approaches, I will almost certainly be publishing more posts on him. But for now, this Easter greeting.