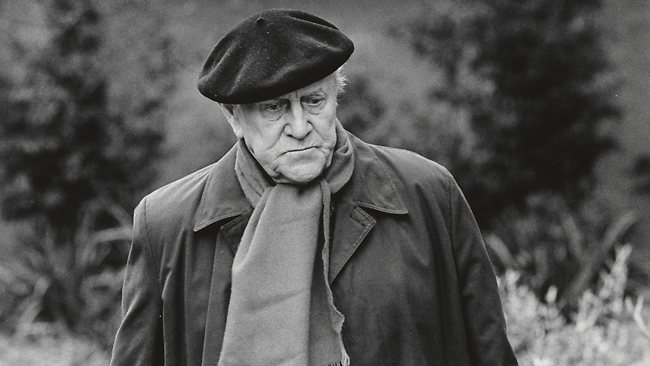

The time has come to speak of Patrick White, whose centenary on May 28th, is fast upon us. I will try to keep this post fairly short because I am currently in such a snit of idolatry that I won’t have anything especially coherent to say. I will simply put forth that, for me, Patrick White ranks along side Henry James, D. H. Lawrence, Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, James Joyce, and Saul Bellow as one of the greatest novelists to write in English in the twentieth century. Hyperbole? You decide:

The woman winding wool held all this enclosed in her face, which had begun to look sunken. It was late, of course, late for the kind of lives they led. Sometimes the wool caught in the cracks of the woman’s coarse hands. She was without mystery now. She was moving round the winding chairs on flat feet, for she had taken off her shoes for comfort, and her breasts were rather large inside her plain blouse. Self-pity and a feeling of exhaustion made her tell herself her husband was avoiding her, whereas he was probably just waiting for a storm. This would break soon, freeing them from their bodies. But the woman did not think of this. She continued to be obsessed by the hot night, and insects that were filling the porcelain shade of the lamp, and the eyes of her husband, that were at best kind, at worst cold, but always closed to her. If she could have held his head in her hands and looked into the skull at his secret life, whatever it was, then, she felt, she might have been placated. But as the possibility was so remote, she gave such a twist to the wool that she broke the strand.

—The Tree of Man

Here is the Whiteian sublime. The physicality he evokes signifies without strain: note her too large breasts, elected from, we gather, a panoply of attributes waxing too large in her plain life. And how about that biblical ninth sentence, gathering into her obsessions the hot night, insects filling the porcelain lamp shade, the eyes of her husband, and finally something vast and forsaken at her core. Of course, we realize upon reaching the end of this passage, which feels more like a perimeter than a terminus, how obvious, the strand of wool will break, lacking, as it does, the heart’s resilience. Whole chapters could be written plucking the riches from the limbs of this passage. And, in a fictional output comprised of some six thousand pages of such passages, this one is more or less garden variety, making the oeuvre of Patrick White one of the most valuable gardens in modern literature.

Which begs the question, why is no one reading him? Why am I practically the only one I know who has even heard of him (apart from those few of my friends who politely let me blather encomiums)? His oeuvre has received sufficient critical attention to persuade me that I am not alone in my admiration. But even those who speak highly of him tend to refer to him as “the most important figure in Australian letters,” or “the first to put Australia on the literary map.” Three cheers for post-White Aussie writers. But White himself is so much more than the down-underwriter of his country’s literary life. He is a world writer in every sense, and should be spoken of in the same terms we reserve for José Saramago, Thomas Mann, Philip Roth, Nadine Gordimer. Why isn’t he?

In my search for answers I’ve been reading his books like mad, reading criticism, trolling the internet, and talking with friends. A distillation of what I’ve found comes down to these four points:

1. Patrick White is a high modernist, making him unfashionable in a post-modern world. As far as I can tell, what this means is that he followed Joyce, Woolf, Pound, and their ilk, in the belief that the old assurances provided by religion, society, and political designations, could no longer bear the weight of modern life and thought. These writers saw a sharp division between literary art and more accessible, or popular, writing. Their books are frank about their difficulties. White has been criticized for the density of his “mannered” or “poetic” prose, his “clotted images”, and fragmented sentences. Naturally, this will limit his readership, but it cannot, on its own, account for his enduring obscurity. His writing is dense, but not daunting. Most of the best of Faulkner is much more difficult. We don’t call Samuel Beckett unfashionable just because no one writes like him now.

2. Patrick White is too pessimistic, too dark, and what he asks us to consider about human nature – ourselves included – is beyond the pale for most readers. I concede this may be so. Many readers have commented on the “shock of recognition” which assails them on nearly every page. But this laying bare, this “truth telling”, to use a rather hackneyed term, this “vivisection”, to use a Whiteian term, is solidly within the purview of the artist. Do serious readers really find the meanness of Nabokov so much more edifying? Does one turn to Eugene O’Neill for a little cheer-up? If White is too relentlessly grim, how, then, make sense of the ever-rising star of Cormac McCarthy, who throws a dense, gorgeous, ball of modernist prose at the violence at the heart of the void? (White’s biographer, David Marr, has said, perhaps too felicitously, that McCarthy could be “up before Media Watch on charges of plagiarism by spirit.) While we’re at it, why don’t we, for the sake of our constitutions, leave Shakespeare on his increasingly dusty shelf while we get a little spiritual r&r.

3. Patrick White was gay. This seems to be the pet gripe of educated gay men of a certain generation, who, to compensate for their admitted fragility in the world, draw strength from being “the only gay in the village.”

4. Patrick White was Australian, making him peripheral to the bossier entities of the literary world. This argument is, sadly, the most persuasive. It grieves me to think that literature may be subject to the same laws as cynical politics: if a country fails to find ascendance in the consciousness of a more established block, it could drop off the map altogether and the privileged parties would be none the wiser. Sam, my partner, has a different take. “There is just so much literature,” he says. His point being, if you are looking to expand your knowledge of even just the essential modern writers, would it occur to you to look to a country known mainly for kangaroos, English convicts, a rather flamboyant strain of machismo, the world’s largest Gay Pride parade, one famous piece of architecture, and an accent often invoked in comedy? Of course there is great writing coming out of that lonely desert of a continent, or at least the thin portion of it strung along its Eastern cost, but its not where most of us would go looking for it. All the same, I would think the fecund sub-genre of post-colonial literature would be happy to hold up Patrick White as one of its shining lights. Can it really come down the banality that Naipaul, Walcott, Gordimer, Coetzee, and Rushdie hale from politically sexier homelands? But then, how to account for Les Murray, widely considered one of the three or four greatest poets currently writing in English. He’s Australian.

None of these explanations finally compel. Factoring in the idea that depth and brilliance in a body of work ought to outweigh whatever might be put in the opposing balance – an apparently fanciful notion in which I persist – here is one further explanation:

5. Ignorance of Patrick White and his work has, quite simply, become a habit. A bad one, I might add.

As with racism, car crashes, and other absurdities, I find Patrick White’s obscurity hard to live with. My question – why is no one reading him? – is not rhetorical, but an honest plea for responses. Someone, please tell me.