Most important in all of life to honor what we’re drawn to. To honor the being drawn. Food, books, sex, a hermit’s life, whatever it might be, we can measure the shriveling of our spirits against the scope of our self-denials. And so, because I’ve never been able to stop picking at the plate of Christianity served to me at birth, even as my taste for belief has waned, I went on pilgrimage.

I spent the last two weeks of May in the UK, stalking Christianity from the island of Iona in the Inner Hebrides to the tidal island of Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumbria, then turning south to Jarrow, and finally arriving at Durham. St. Columba, St. Aiden, St. Hild, St. Wilfred and St. Cuthbert had all been unknown to me before. Now these shadowy figures, who lived roughly between the years 521 and 687, have staked a claim to my imagination – territory I’m happy to cede.

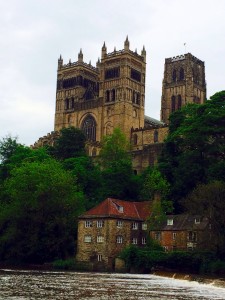

But it was a place rather than a person which drew me first and undid me at last. Above a bend in the river Wear rises Durham Cathedral. Several years ago, for reasons now lost to me, I became fascinated by the great English cathedrals, and Durham in particular. The images I saw of it’s immense nave flanked by massive Norman piers gouged with chevrons, spirals and diamonds, its twin west towers, more fortress-like than holy, and more believably hewn from the promontory above the river than built on it, compelled a love wanting consummation. Now, having consummated, I can say, without fear of overstatement, that it is the most extraordinary building I have ever set foot in.

But it was a place rather than a person which drew me first and undid me at last. Above a bend in the river Wear rises Durham Cathedral. Several years ago, for reasons now lost to me, I became fascinated by the great English cathedrals, and Durham in particular. The images I saw of it’s immense nave flanked by massive Norman piers gouged with chevrons, spirals and diamonds, its twin west towers, more fortress-like than holy, and more believably hewn from the promontory above the river than built on it, compelled a love wanting consummation. Now, having consummated, I can say, without fear of overstatement, that it is the most extraordinary building I have ever set foot in.

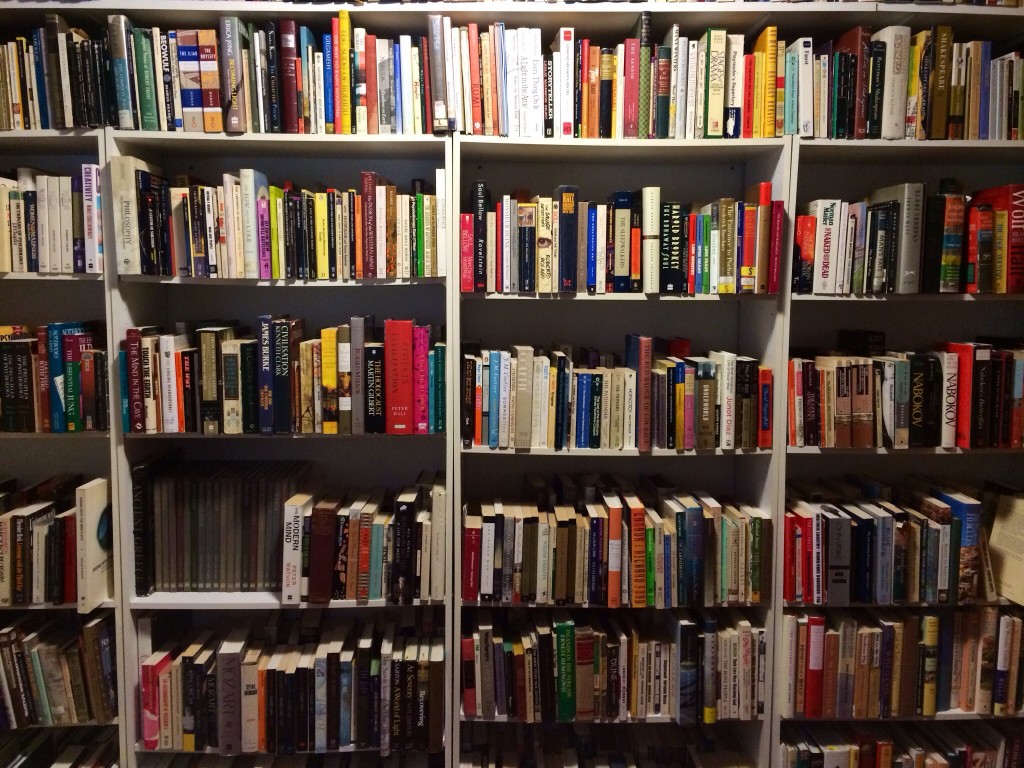

Because reading is my way, I spent the month and a half before leaving and the month since my return immersed in the literature of this time and place. I read several extended essays about Durham Cathedral, including an extraordinary one from 1887 by Mariana Griswold (Mrs. Schuyler) Van Rensselaer, America’s first female architecture critic. I read a history of Holy Island (as Lindisfarne is sometimes called) and a gorgeous and scholarly book on the Lindisfarne Gospels, an illuminated Gospel book from the early 700’s, second in renown only to the the Book of Kells. I read Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written in 731, which, scintillating title aside, reads like a sequence of fairy tales. I read a collection called The Age of Bede, which features the Lives of St. Cuthbert and St. Wilfred, and the fanciful “Voyage of St. Brendan”. I read John Philip Newell’s Listening for the Heartbeat of God, which contrasts the Christianity of the Celts with the competing, and ultimately dominating, Roman version. I read two novels by the great Fredrick Buechner, Godric, and Brendan, about two relatively obscure saints whose lives nonetheless encapsulate the earthiness and earnestness which seemed to characterize the religious fervor of that time and place. I’m currently reading Adomnán of Iona’s Life of St. Columba. Perhaps this will sate me. At least for now.

Because reading is my way, I spent the month and a half before leaving and the month since my return immersed in the literature of this time and place. I read several extended essays about Durham Cathedral, including an extraordinary one from 1887 by Mariana Griswold (Mrs. Schuyler) Van Rensselaer, America’s first female architecture critic. I read a history of Holy Island (as Lindisfarne is sometimes called) and a gorgeous and scholarly book on the Lindisfarne Gospels, an illuminated Gospel book from the early 700’s, second in renown only to the the Book of Kells. I read Bede’s The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written in 731, which, scintillating title aside, reads like a sequence of fairy tales. I read a collection called The Age of Bede, which features the Lives of St. Cuthbert and St. Wilfred, and the fanciful “Voyage of St. Brendan”. I read John Philip Newell’s Listening for the Heartbeat of God, which contrasts the Christianity of the Celts with the competing, and ultimately dominating, Roman version. I read two novels by the great Fredrick Buechner, Godric, and Brendan, about two relatively obscure saints whose lives nonetheless encapsulate the earthiness and earnestness which seemed to characterize the religious fervor of that time and place. I’m currently reading Adomnán of Iona’s Life of St. Columba. Perhaps this will sate me. At least for now.

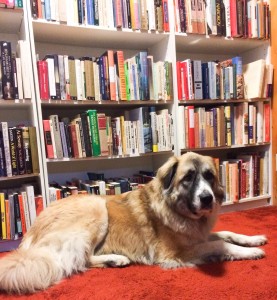

If calling the come-to-Jesus moment I had with my own bookshelves around the time I began preparations for traveling to the UK a “parallel pilgrimage” is rather too precious, it nonetheless came from a similar place: the need for a shift in perspective. In my February post, “On the Meaning of Books” (https://thestockholmshelf.com/2014/02/on-the-meaning-of-books/) I wrote that each of the thousand plus books in my collection carries “a condensation of emotion” unrelated to its specific content. I also wrote that a large portion of these books belonged to my partner Sam who passed away a year ago in May, and that holding on to them was, in the land of magical thinking, a way of holding on to him. “There are books in the house I will never read,” I wrote, “a great many of which I don’t even want to. But I part with them at a cost.” Conversely, sometimes honoring what one is drawn to entails the release of excess. Having too much of anything inevitably becomes about the having, obscuring the beauty of the thing itself, the thing which draws. I said I had over a thousand books. In retrospect, it was more in the neighborhood of three thousand. Somewhere between a third and a half of them had to go.

If calling the come-to-Jesus moment I had with my own bookshelves around the time I began preparations for traveling to the UK a “parallel pilgrimage” is rather too precious, it nonetheless came from a similar place: the need for a shift in perspective. In my February post, “On the Meaning of Books” (https://thestockholmshelf.com/2014/02/on-the-meaning-of-books/) I wrote that each of the thousand plus books in my collection carries “a condensation of emotion” unrelated to its specific content. I also wrote that a large portion of these books belonged to my partner Sam who passed away a year ago in May, and that holding on to them was, in the land of magical thinking, a way of holding on to him. “There are books in the house I will never read,” I wrote, “a great many of which I don’t even want to. But I part with them at a cost.” Conversely, sometimes honoring what one is drawn to entails the release of excess. Having too much of anything inevitably becomes about the having, obscuring the beauty of the thing itself, the thing which draws. I said I had over a thousand books. In retrospect, it was more in the neighborhood of three thousand. Somewhere between a third and a half of them had to go.

Many books turned out to be obvious deportees. How we managed to accumulate no less than seven books on English usage, eight French textbooks, four copies of Invisible Man and two complete copies of Remembrance of Things Past in the Moncrieff translation I’ll never know. I didn’t need both the collected and selected poems of Auden. And really, will my life ever be long enough to read Sacajawea, no matter how good a read people say it is?

Others required harder choices. Which of the ten anthologies of American poetry should I keep? How many Chinese cookbooks does one need, or which of the eight Julia Childs? Hard indeed was the choice to let go of Jane Smiley’s early novel The Greenlanders. It was one of the first gifts I gave to Sam and I had written an inscription to him on the fly leaf. I knew that I would likely never read this probably very good book. But what would it mean to send it on? After much going back and forth about it, I realized that there was nothing that it could be a record of that hadn’t already left more indelible traces in my heart than I could ever count.

My friend Nathan came over several times during this process to nominate some titles for the used book store where he works, but my collection was so idiosyncratic that this amounted to a relatively small portion. So I threw a book give-away party. I invited friends who I knew were readers, prepared a feast, then told them they couldn’t eat until they had each claimed a healthy stack. Whatever was left would be donated. Bittersweet at first, but ultimately a joy to see my friend Richard carry away Sam’s Le Rouge et Le Noir (my French will never be up for that) and my old Maud translation of War and Peace.

My friend Nathan came over several times during this process to nominate some titles for the used book store where he works, but my collection was so idiosyncratic that this amounted to a relatively small portion. So I threw a book give-away party. I invited friends who I knew were readers, prepared a feast, then told them they couldn’t eat until they had each claimed a healthy stack. Whatever was left would be donated. Bittersweet at first, but ultimately a joy to see my friend Richard carry away Sam’s Le Rouge et Le Noir (my French will never be up for that) and my old Maud translation of War and Peace.

In the early monastic life of the British Isles there was a tradition of sacrifice known as the peregrinatio, or “Pilgrims of Christ”. It was one of the holiest callings a monk could receive, requiring that he give away his few belongings and set off from the monastery which had nurtured and sustained him, leaving his kin and his country, often never to return, and go only where Christ led him. Adomnán, I read, believed this was St. Columba’s purpose in sailing from Ireland to found the monastic community on Iona which was to have untold influence on the religious life of Britain for centuries to come. Without subtracting from the weight of this great call as received by certain remarkable people, it is, in some obvious ways, the most ordinary of all callings, heard by each of us at the dawn of consciousness. From the moment we are able to make the choice to extend ourselves toward what draws us or pull back in fear, or prudence, we are learning how to respond. Our past, our security, country and kin, it all gets left one way or another, whether grasped after or risen from, and the best way to make God laugh is to tell God your plans. And perhaps the call is less difficult than we fear. I’m not sad I gave those books away.

Here ends my explanation as to why I haven’t posted anything for the past two months. I expect that in July things will settle down a bit and I’ll get back on track. Look for a review of Claude Simon’s luminous The Trolley.