I.

I’ve never chased autographs. Not on principle; simply, I’ve never put myself in the path of anyone whose signature might carry for me a valence. To do so requires a quality of ego which, for all my petty narcissisms, I evidently lack. I love the story of the man who followed William Golding into a men’s room in Stockholm to requested his autograph. To have the…frame of mind to make such an approach – what I wouldn’t give.

A few authors’s penmanship samples have dropped into my collection. As an eight-year-old I stood in line, all day it seemed, at the May D&F store in downtown Denver to have Theodor Seuss Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, sign my copy of The Lorax. I have no idea where this book is now. Two more autographs came my way just out of college, while working in a bookstore at Stapleton International Airport: I recognized Erica Jong the moment she walked in off the concourse. We had just sold out of The Devil At Large, her then recently published biography of Henry Miller, but we did have one copy of Every Woman’s Blues, which I made haste to put by the cash register before she approached. “Oh,” she said, “You have my book.” Whereupon she signed it – “Best wishes to David and Sam, Erica Jong”, across the title page such that the eye need never alight on the actual title – and, with my employee’s discount, I bought it. Annie Proulx was far less prolix when she signed The Shipping News – “E. A. Proulx”, like the title’s bastard sibling wavering fiercely in the surrounding glare of page.

Until last year, this comprised my entire collection of autographed books. Then my friend, Viet Dinh, who teaches writing at the University of Delaware, came into town with a copy, signed especially for me, of Twilight of the Superheroes, by the American master of the short story, Deborah Eisenberg.

Except for the Dr. Seuss, which required mastering my child’s legs and bladder, I did nothing for any of these.

II.

Death is an ass, even when it doesn’t quite strike. For nearly a month it was forever darting out of sight whenever one of us entered Sam ‘s hospital room. It wasn’t fooling anyone, we all knew it was there. For form’s sake, as with someone else’s rotten child, we played along, talked to Sam, held his hand through his deliriums, fed him ice chips, celebrated the ice chips, watched a slightly soured strength creep back into his etched limbs. Did you see a little snot-nose slip in? Who, me? No. Did you?

Death is a despot, exacting from you all your thoughts, more than you have to survive on yourself.

III.

Viet is a gifted writer. Find a copy of the 2009 PEN/O’Henry Award Stories and read “Substitutes”, in which his narrator recalls childhood in Vietnam, and the string of substitute teachers hired to teach his class, each of whom mysteriously failed one day to show up. It is the kind of story that sneaks up on you, then stays. Keep your eye out for his first novel, about the experiences and relations among disaster relief workers. He’s not shared with me the title, but last we spoke, he was on the prowl for a publisher.

Viet chases autographs. Sometimes literally. At a writers conference in Washington D.C., he pursued Orhan Pamuk the length of the Washington Mall to procure the great man’s scrawl. I could hardly speak to him after he told me this, so envious was I. The author of (and, wonderfully, the builder of) The Museum of Innocence is one of my foremost author crushes. Viet was the first to tell me about László Krasznahorkai, the great Hungarian novelist, whose Nobel Prize is, at the moment, rising in The Swedish Academy’s warming oven, and whose The Melancholy of Resistance is currently giving me giddy fits of amazement. Viet met him, which will mean he has at least one example of his handwriting on something.

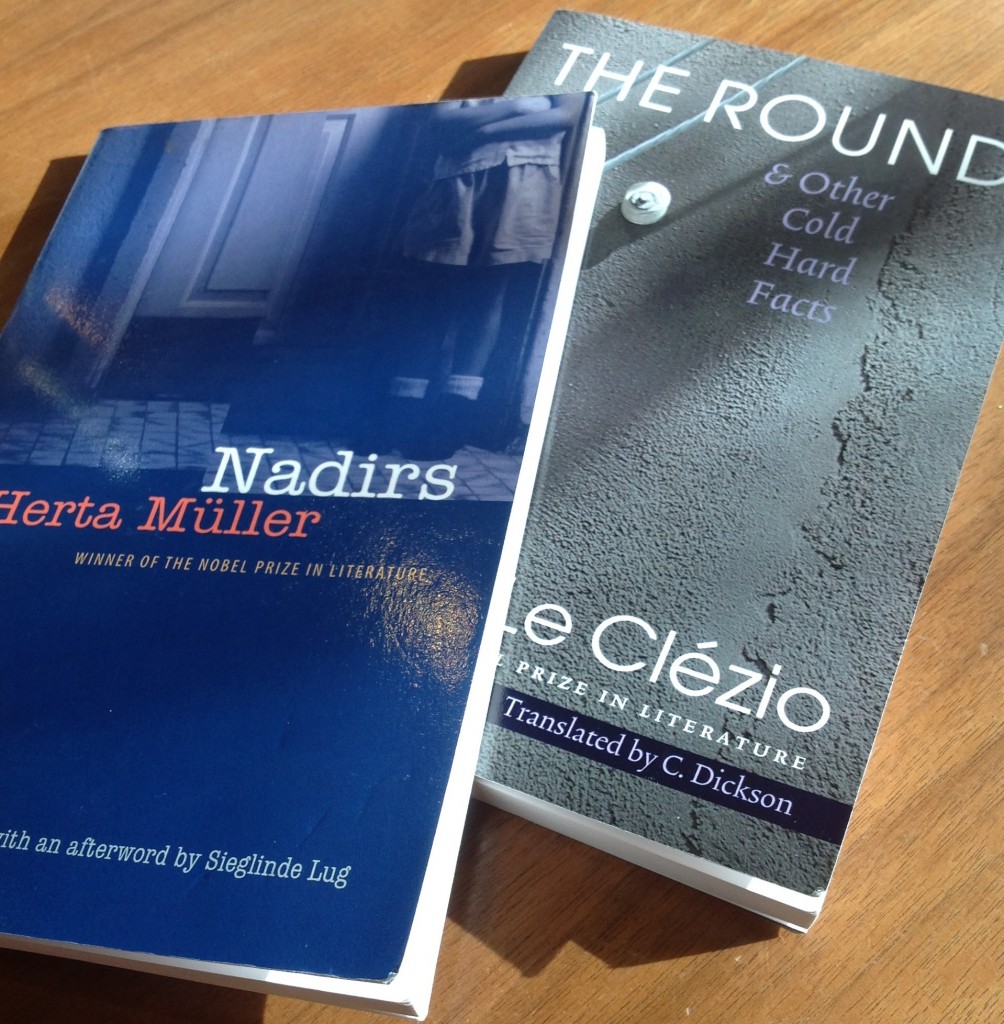

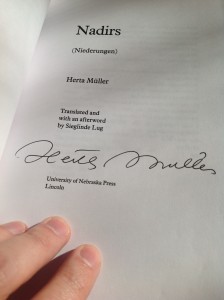

This summer, he presented me with, not one, but two remarkable gifts which left me rather at a loss for words. Regular readers of my posts will no doubt find this hard to believe. Nonetheless, when he handed me a signed copy of Herta Müller’s Nadirs I was helpless to arrive at a proper response. Into my hands he had placed an object which had been held in the hands of a Nobel Prize winner. What, really, does one say?

“I haven’t read her yet,” I ventured. “Do you like her?” Such a weak question. “Oh yes,” he said. “She’s excellent. I just read her new book, The Hunger Angel. Wonderful.”

“I haven’t read her yet,” I ventured. “Do you like her?” Such a weak question. “Oh yes,” he said. “She’s excellent. I just read her new book, The Hunger Angel. Wonderful.”

I turned this somehow mysterious object over and over in my hands, as if the existence of the black fountain pen ink on the title page made it less understandable as an actual book, trying to take in alternately the austere blue university-press-style cover and the author’s photograph on the back, which shows an apparently humorless woman whose youthful appearance is belied by a few lines discernible around her large, steady eyes, hair close-cropped in a manor associated with American lesbians of a past decade, the shoulders and high collar of a dark and probably stylish coat, small dangling earrings apparently oblivious of their role as ornament, heightening rather than allaying the desolation of the cheekbones. So unlike a Nobel laureate. Which begs the question, just what is a Nobel laureate like? I tried to picture her holding the pen with which she’d signed this book. My book. “She looks different now,” Viet said. “She’s older. Her hair is straight, framing her face. She’s very severe, which makes me love her all the more.” His eyes danced; I could see him seeing her. And I knew that, in at least one sense of the word, he meant what he said – about loving her.

And what I really found myself wanting, or believed I wanted in that moment, and had not the moment before, and which I could not have said, which is why I could, finally, say so little, was Herta Müller herself.

IV.

There is a compelling illusion that attends an autograph, the illusion that you are actually, magically, connected to the person whose signature you’ve come to possess. And being so connected means somehow touching that person’s importance. And the thing about importance is the sense of permanence it holds, it’s promise of immortality. An autograph is a fetish to wield, like all fetishes, against death.

V.

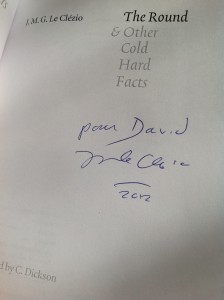

Viet likes a tea shop on 15th and Platte called “House of Commons”, and it was there, over cucumber sandwiches and Darjeeling, that he presented me with his second gift, The Round & Other Cold Hard Facts, by J. M. G. Le Clézio. The Müller had primed me and, like a gouche hausfrau checking the hallmark on a plate, I surreptitiously glanced at the the title page. Shouldn’t it have been enough that he he had brought me the book? The giving and receiving of books is one of the primary forms of social commerce among my friends, and here was an especially thoughtful offering, knowing as he does that I keep this blog. But something in my psychical basement had been stirred from recumbence, a need, bleached and crying, which believed its relief could be achieved by a nod from a notion of greatness. An autograph is not a Chartres, but in the moment, if prepared for, it can feel, if not like something transcendent itself, then a gratifying brush with something that is. An autograph invites you to forget that it’s medium is friable. Ink and paper, when it comes down to it, won’t outlast much. How else could the Dead Sea scrolls so astonish? It is quite possible, however, that it will outlast you.

My friend Nathan, who knows about books as objects, guessed that a Nobel laureate’s autograph in a fourteen dollar paperback could jump the price to sixty or seventy dollars. “Enough of these, and I could move to Mallorca?”

My friend Nathan, who knows about books as objects, guessed that a Nobel laureate’s autograph in a fourteen dollar paperback could jump the price to sixty or seventy dollars. “Enough of these, and I could move to Mallorca?”

I looked across the table at Viet, trying to ascertain whether he had caught me peeking. While he spread lemon curd on his scone, I opened the book outright. There it was. This time in blue ballpoint and friendlier for it: “pour David/ —Le Clézio/ 2012” Look. He even knew my name.

VI.

When Herta Müller won the Nobel Prize in 2009, Sam’s response was at first dismissive. “Another dour Eastern European.” But his opinion changed, and decisively, when he read The Appointment. He proceeded to buy all of her books then in translation (save Nadirs). It was different with Le Clézio. His mild curiosity dissipated upon reading the short story the New Yorker ran in conjunction with the Nobel announcement. He found it thoroughly dreary and has not been able to muster any interest in him since.

A few recent Nobel laureates are close to his heart. Wislawa Szymborska is a nearly religious figure for him. Imre Kertesz’s Kaddish for an Unborn Child moved him as deeply as any modern novel has. Towards the end of summer, as his health was closing in, he instinctively reached for Saramago, the great opener; he got only a little past the strange, luminous passage of the annunciation in The Gospel According To Jesus Christ before the crisis took root, and his life as usual. The book followed him to his various rooms on ever-ascending floors of St. Joseph’s, waited for him on the table behind the metal tree hung with tubes for steroids, saline, and nutrients, waited as his mind, body, and spirit guttered.

He’s reading again, for short spans. He listens to music in earnest. His own especially, and Debussy’s. Soon, perhaps, he’ll have the reserves to see where the annunciation leads.

VII.

Sam won’t be home for Thanksgiving this year. I think when he does return I’ll ask him to write his name. Perhaps on the back of an envelope. I’ve always loved his handwriting, impossible to read but beautiful, like a hybrid of Korean and Arabic. I’ll ask him to write his name, maybe three times, on whatever comes to hand, an old receipt, the back cover of the Saramago, a paper sack we use for recycling. I’ll ask him to write his name no more than ten times, on the walls maybe, and the dashboard of the car. Just ten times a day. The side of the house could use the lift, and the trees on the block. It won’t be much to ask, really, every day, for the next year or two. Or however long it takes.