Listen to how one rebel defends revolution in Egypt:

“History remembers the elite, and we were from the poor — the peasants, the artisans, and the fishermen. Part of the justice of this sacred hall is that it neglects no one. We have endured agonies beyond what any human can bear. When our ferocious anger was raised against the rottenness of oppression and darkness, our revolt was called chaos, and we were called mere thieves. Yet it was nothing but a revolution against despotism, blessed by the gods.”

These are the words of Abnum, leader of a revolution which boiled up at the end of Egypt’s Old Kingdom (circa 2125 B.C.E.). That is, they are the words of a character named Abnum, presented as the historical leader of an uprising, which may or may not have actually happened, against a despotic King during the waning years of Egypt’s Old Kingdom. Rather, to say it as it is, they are the words of Naguib Mahfouz, given to his character, Abnum, in his short novel, Before the Throne.

Perhaps you would have believed me if I had said that these words had risen steaming from the throats of angry Egyptians pressing into Tahrir Square earlier this year? This month? This is how Mahfouz’s translator and biographer Raymond Stock reads them:

“Change “thieves” to “foreign agents,” make the revolt not one of just the poor, but of people from all classes and walks of life, replace “gods” with God, and we are in Cairo’s Tahrir Square of the last few months.”

He wrote Before the Throne in 1983, five years before winning the Nobel Prize, two years after the assassination of president Anwar al-Sadat. In the novel, scores of Egypt’s leaders, from the First Dynasty through Mubarak, are brought before the Court of Osiris to defend their actions. The book is a rarity among Mahfouz’s thirty five published novels, an overt ideological statement. Perhaps, considering all he had witnessed in his already long life, he felt it was time.

Like Odysseus Elytis and Czeslaw Milosz, two of the three other Nobel laureates who, were they living, would have celebrated their 100th birthdays this year, Mahfouz lived through an era of great national upheaval. He was born in Cairo’s comfortable, middle-class Gamaliya district durning the final years of British colonial rule and under the waning influence of the Ottoman Empire. In 1919, at the age of seven, he witnessed nationalist protesters gunned down in the street right in front of his home. He lived through the reign of King Fuad, first ruler of the newly sovereign Egypt, and that of his son, King Farouq, who was deposed in the coup of 1952 which presaged the establishment of the republic and of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s takeover in 1954. He lived through the bombing of Cairo by France and Britain in collusion with Israel during the Suez Canal crisis of 1956, only to become a supporter of the 1978 Camp David Accords, the gesture of reconciliation with Israel which sealed the fate of Sadat. Mahfouz’s vocal position on the Accords led to massive boycotts of his novels throughout the Arab world. In the last two decades of his life, he, along with the rest of Egypt, lived under Hosni Mubarak’s brutal and corrupt American supported military dictatorship, and saw the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. In 1994, this fundamentalism got him in the neck, literally, when he was stabbed by two men on his way to one of the coffeehouse’s he loved to frequent. The attack was intended to exact revenge for his novel, Children of Gebelawi, written three and a half decades earlier, in which he portrays God, Adam, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad as ordinary people, mere mortals operating in a Cairo neighborhood.

Who doesn’t wish he had lived to see his centenary, a year for Egypt like no other in recent memory. Regarding the January 25th revolution which toppled Mubarak, his daughter, Faten Mahfouz, told the American University in Cairo Press, ” I think he would have been happy, like most Egyptians, including all intellectuals. A lot of people had been suffering.”

Since 1996, the Mahfouz Medal for Arabic Literature has been awarded to the best contemporary novel in the Arabic language which is not also available in English translation. As part of the Award, the winning book is translated into English. The award is given on December 11th, Mahfouz’s birthday. Today, in a surprise move, the award was given, not to a person or a book, but to a curious but vital abstraction: “the revolutionary literary creativity of the Egyptian people.”

Since 1996, the Mahfouz Medal for Arabic Literature has been awarded to the best contemporary novel in the Arabic language which is not also available in English translation. As part of the Award, the winning book is translated into English. The award is given on December 11th, Mahfouz’s birthday. Today, in a surprise move, the award was given, not to a person or a book, but to a curious but vital abstraction: “the revolutionary literary creativity of the Egyptian people.”

In announcing the prize, committee member Samia Mehrez said, “Over the past year, Egyptians have articulated their ownership of space, body and language through a myriad of creative, performative and cultural practices whose semiotics, aesthetics and poetics have not only inspired sister uprisings worldwide but have also created sustaining solidarities throughout the world.”

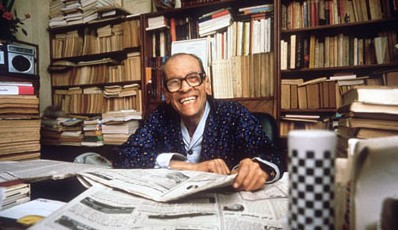

In future posts, I will share with you certain questions about Mahfouz that have arisen for me, and my personal experience of reading his novels. But for now, I leave you with this You Tube portrait of the man whom many credit with creating the Arabic novel. Please watch it. I think you will find it fascinating.