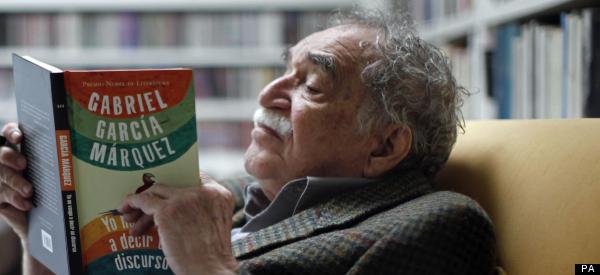

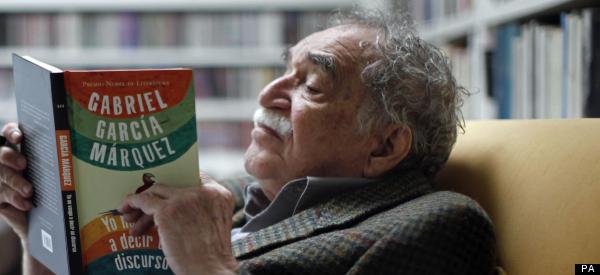

Just as, inevitably, the scent of bitter almonds always reminded Dr. Juvenal Urbino of the fate of unrequited love, so there is a cadence of sentence, that always reminds me, in my evil hours, of what I love. Extravagant, poised, penetrating sentences. Sentences which, contrary to contemporary writerly morality, draw my attention to themselves. In the way Montserrat Caballé’s voice draws me into its own sound as she sings “Costa diva”, every tremulous note in every phrase extending beyond mortal breath. I hear it and requital becomes moot; I love again. That Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote more, and more consistently, such sentences than most twelve other writers combined, makes him one of Love’s great exponents. An avatar of Eros. Imagine signing that on your taxes.

So that when, early this month I got a text from my friend Nathan, saying that Jaime Garcia Marquez had made a public announcement that his older brother, Gabriel, now 85, was suffering from dementia and, in all likelihood, would not be writing any more, I felt a moment of disorientation. Remember, as a child, emerging from the waking dream of your life to discover that your parents were not where you had, you thought, left them? You felt the earth roll. Without realizing it, I had come, in some way, to rely on Don Gabriel being on the rolling earth, somewhere, breathing air continuous with the air I breath, somewhere working, writing those reminders to love I so regularly require.

Nathan, a slender man in his early thirties, quick of wit and large of heart, is one of the hidden treasures of the North Denver book scene. He works at West Side Books, one of those remodeled auto garages which belie their former incarnations less through architectural traces than through arcane profusion, book mold replacing axle grease and sparking metal in the nose, hopelessly overflowed shelves replacing hydraulic lifts. Nathan works among the books a bit like a grounds keeper tends a public garden, planting, weeding, mulching, watering, all the while steadily reading his way, both in English and Spanish, into a formidable mastery of Latin American literature. His knowledge already encompasses wide swaths of the literary landscape out of sight to most of us who are not ourselves Latin American. His current obsession, for example, is the apparently great Argentine writer, Juan Jose Saer. Nathan’s desire, rather avaricious, for the horde of the mind is one of the things I love about him. No one better to have delivered the hard news about Gabo.

The day before, he had texted me about the Argentine.

“Who the effen wg sebald is Juan Jose Saer!?” I sent.

His reply came a few minutes later: “A great Argentine writer whose works weren’t, apparently, exotic or magical enough for the North American publishers to market to our name-brand-hungry audiences when they started appearing in the late ’60s. Something like Cortázar meeting Faulkner from what I’ve read so far.”

What he was referring too, I soon learned, was the germ of a backlash among younger Latin American writers against the literary esthetic known popularly as magic realism, of which Gabriel Garcia Marquez is the most famous exponent. In the mid 1990s, the germ sprouted verdantly and bloomed into a two-headed Godardian attack against the cultural hegemony of the major North American publishing houses: In Mexico it became known as “La generación del crack” (The Crack Generation), while elsewhere in Latin America, it became known, rather bitingly, as “McOndo”, a subversive conflation of McDonald’s with Macondo, the mythical setting of One Hundred Years of Solitude. The two movements differed ideologically, but agreed on a repudiation of Realismo mágico, conversely known as Macondismo. The authors of these movements believe that magic realism too easily reduces real life as lived by real Latin Americans to stereotype and kitch, and was not equal to the portrayal of the diverse, complex, and messy Latin American moment.

Then, the announcement that Gabo suffers from dementia.

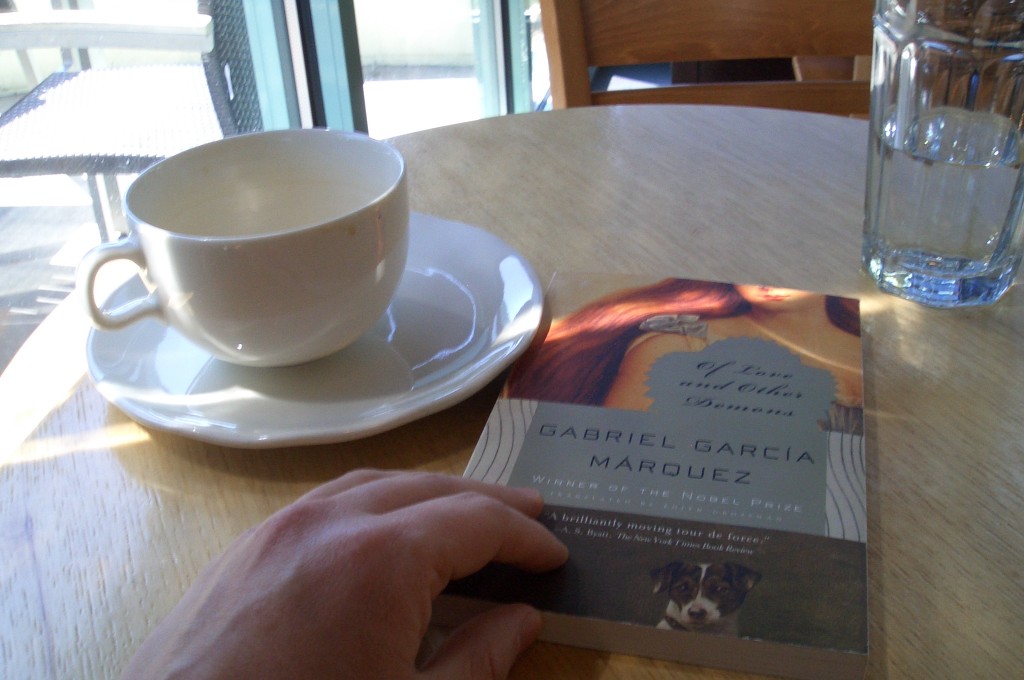

I texted him: “Terrible news! He’s been a fixture for so long in my literary world. Actually, calling it my “literary world” sounds vaguely silly, and certainly reductive. Garcia Marquez, Annie Dillard, now Patrick White, all the others, they are my world, simply, as much as you are, and Sam, and Bach, and Rachmoninoff, and damned old Protestantism. When one of those fixtures prepares to move, so autonomously, out of the picture, it’s rattling. I’ll still have his books. All of him I ever had, really, or could have. But it has been a tacit reassurance knowing he’s around.”

He texted me back: “I know what you mean. But… All types of madness were always just around the corner in all of his works. I’d still so love to have tea with him in his living room, whatever condition he’s in.”

Me: “I wasn’t aware that he has been the object of some resentment among Latin American authors. I wonder if its the same species of resentment many Japanese directors held against Kurasawa.”

Nathan: “All the Latin American talk against magic realism was never against him, just against publishers only wanting works that cheaply replicated that aspect of his style and stereotyped Latin American culture. McOndo tried to open doors for writers who had trouble publishing because their work wasn’t about country folk in sombreros feeding their burros which, incidentally, fart prognosticating ghosts, while the menace of a dictator is felt from afar. The realities of life in Latin American countries has changed a lot in the last fifty years, and those realities, and the strength of other Latin American literary traditions, and the distinctness of individual nations, are not well represented by works that pander to a market demand for magic realism. But Gabo himself, as far as I can tell, is universally venerated.”

Me: “Thanks for the clarification. The perfidy of a consumer public and its lackeys faulting gifted artists for not being sufficiently someone else.”

Nathan: “These writers are as good as it gets, but aside from possibly Bolaño, I don’t think any of them, at least that I’ve read, achieve Garcia Marquez’s grandeur. What royalty he truly is. So thankful for the many books he gave us!”

The conversation continued, through text, and then over dinner at our house. Nathan suggested that a gifted Latin American writer trying to carve out a space in the shadow of Gabriel Garcia Marquez was a bit like a 19th century German composer working in a different vein from Wagner while Wagner was still living. Sam asserted that, while the point was taken, the analogy breaks down because of the Brahms/Wagner divide and how passionate and how evenly split the two factions were. And as we talked, the colloquy become ever less about its apparent subject. Even as we continued to lay before each other our offerings, what we knew about the books we’d read, the music we’d heard, the history we’d learned, in hopes of having them returned to us in such a way that we might ourselves understand them better, it became apparent that the real colloquy was on love. The love of these artists for their culture and craft. Our love for them, for the company they keep us. Our love for each other. Our love for our own lives, of all in ourselves we want affirmed. We’ve known all along, though we adore forgetting, that we live in a world in which a man with orange curls aching on his tormented head can walk with legally purchased weapons into a movie theater not a dozen miles from where we live, and try to appease the other demons by laying waste to the lives he finds there. We live in a world in which the political blather narrows to absurdity the native human capacity to look up and to look around. All that Nathan and I texted, all the three of us said over vegetarian food, all that Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote, and all that his dissenters hold true, Brahms, Wagner, the rest, all runs counter to this decay. It is the resistance we stage against the public dementia. Such resistance is, practically speaking, futile. Only, many years later, or tomorrow, when we face the firing squad – and we all will, one way or another – we will remember that distant afternoon, or the evening last week, when we took each other to discover, not ice, but our own loves, and through those loves, our lives.

Gabo knew this. And I believe that, whatever lines of magical reality his mind now follows, he always will.

Over the weekend the vultures got into the presidential palace by pecking through the screens on the balcony windows and the flapping of their wings stirred up the stagnant time inside, and at dawn on Monday the city awoke out of its lethargy of centuries with the warm, soft breeze of a great man dead and rotting grandeur. Only then did we dare go in without attacking the crumbling walls of reinforced stone, as the more resolute and wished, and without using oxbows to knock the main door off its hinges, as others had proposed , because all that was needed was for someone to give a push and the great armored doors that had resisted the lombards of William Dampier during the building’s heroic days gave away.

— The Autumn of the Patriarch, opening lines