What was Chinua Achebe thinking? It was his only manuscript, and handwritten.

What was Chinua Achebe thinking? It was his only manuscript, and handwritten.

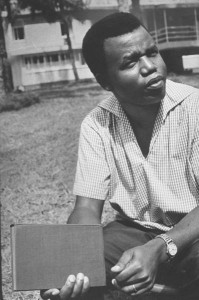

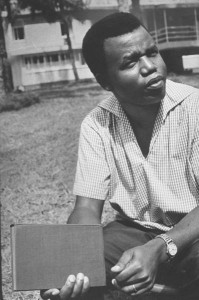

I picture him as a young man living in Lagos, carefully stashing in his suitcase the manuscript for the novel he has begun. It is 1956, and the BBC has given him a scholarship to study in London. The first non-Nigerian soil he will have ever set foot on will afford him a glimpse of the world from which had come his beloved Dickens, Shakespeare, Tennyson, as well as the captivating colonial pablum of Sir Henry Rider Haggard, whose tribal African characters, malign brutes driven by bestial cunning, had filled Achebe with a distressing loathing for his own. It had also given him Joseph Conrad, a writer of greatness, himself an immigrant, who, ironically, may have shaped his destiny as a writer more than any other because there came a moment when he realized he was not numbered among the noble race on Marlow’s boat steaming up the Congo in Heart of Darkness, “rather, I was one of those unattractive beings jumping up and down on the riverbank, making horrid faces.” Conrad’s famous book set up a fortuitous dissonance between his reading and the eloquence of the Christian ministers and Igbo elders who formed him as a child, one which made the manuscript he had so carefully tucked under his few clothes in that suitcase a fierce necessity.

London. Dickens’ hotbed: I imagine the twenty-six year old Chinua Achebe, furrow-browed, and, on account of the latitude, just a little chilly, taking in his new surroundings, running all the novel sensory input coming at him against all he knows of life in Nigeria, learning as much about his homeland as about London. Less color here. Fewer flies. Post-war scarring notwithstanding, it is clear where power lies. Things fall apart here too, but no one lets on.

He meets a man named Gilbert Phelps, a novelist and, incredibly, a critic of African literature. Phelps introduces this intense young African to the English way of drinking pints, over which they discuss the work of Achebe’s compatriot, Amos Tutuola, whose novel, Palm-Wine Drinkard, had finally been published in England in 1952, and about why it had taken six years. They go back and forth about the work of Achebe’s other compatriot, Cyprian Ekwensi, whose novel, People of the City, had come out just two years earlier to become the first book by a Nigerian to have made it onto international shelves. How amazed they both must be to be talking about these things. Achebe goes back to his quarters, spends a sleepless night, by the end of which he has reached a decision. He gathers up his manuscript and brings it to Phelps. His novel, set in the late nineteenth century, about a local Igbo (or “Ibo”) wrestling champion and yam farmer, whose people suffer the influence of British colonialism and Christian missionaries, is now in the hands of one of the race of colonizers. One of those on the riverbank has handed over the product of his mind to one on deck.

Phelps loves what he reads. He tells Achebe that he has produced a great book which must be published. But Marlow’s world has left him changed. There is so much more that must be said than he had realized. Back in Lagos he finds that his manuscript has, quite unbeknownst to him, divided in two. He takes up what has become the first part, in which his former wrestler, Okonkwo, rises out of poverty to become a wealthy landowner, then a murderer, and finally a suicide, and shapes it into a tragedy worthy of Aeschylus. The pages burn so bright with counter-Conradian fire that he can work well into the heavy nights without a light. One morning, he wakes, steps out into the sub-Saharan sun, blinks, rubs his nose once, and realizes he has finished.

Now, what’s an African writer to do? He knows he has something powerful on his hands, a fiction different from that of Tutuola, different from Ekwensi, whom he admires. But he knows, too, that the world into which he wants to introduce it, like a firebrand onto the deck of a Congo-trolling steamboat, will snuff it like a cigarette butt unless it has the right look. And so he gathers up the pages and like a parent sending off a child he sends them, along with 22£, back across the continents, to a typing service in London. He has done the right thing. Surely.

And I’m left wondering what he was thinking. Upon what reserves of faith did he draw, tapping what vein of idealism, or was it plain naiveté, to conceive that he could entrust the one and only copy of his manuscript to the transcontinental post, bound, unheralded, for the crowded desks and files of a typing service in London, without imagining that it could be lost along the way, or, assuming it arrived as intended, that those who received it would not regard it – a novel apparently, from Africa? – as some kind of joke? I find it moving beyond words that he was already living, mentally, in the kind of world he hoped his novel would be, in some small way, an agent of.

And it seems for a moment he will be vindicated. How quickly he tears open the envelope with the agency’s reply. It says that for two typed copies they require 32£, which he promptly sends, then settles in to wait out the weeks. Then the months. A season or two. Those around him begin to note to each other how emaciated Chinua is becoming. After many months, it seems clear that his manuscript is lost – to him, and to the world. Late in life he will acknowledge that the fate of his own character, Okonkwo, could have been his as well.

To those among us not destined to be artists, let us hope will fall the role of advocate. Angela Beattie, an Englishwoman abroad, could choose not to bother with her brainy and ever more apparently troubled employee, Chinua. Surely she has enough on her mind unpacking how she has come to hold this position with the Nigerian Broadcasting Service here in swarming Lagos. But she does bother. She finds out what has left Chinua so reduced, and when next she travels home to London, she seeks out the delinquent agency and unleashes a righteous furry. “And when they saw a real person come out of the vague mess of the British colonies,” Achebe will later write, “they knew it was no longer a joke.” He got his copy – one copy, never the paid-for second.

To those among us not destined to be artists, let us hope will fall the role of advocate. Angela Beattie, an Englishwoman abroad, could choose not to bother with her brainy and ever more apparently troubled employee, Chinua. Surely she has enough on her mind unpacking how she has come to hold this position with the Nigerian Broadcasting Service here in swarming Lagos. But she does bother. She finds out what has left Chinua so reduced, and when next she travels home to London, she seeks out the delinquent agency and unleashes a righteous furry. “And when they saw a real person come out of the vague mess of the British colonies,” Achebe will later write, “they knew it was no longer a joke.” He got his copy – one copy, never the paid-for second.

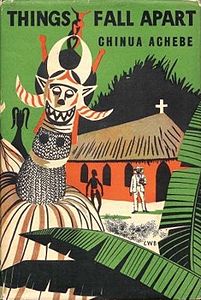

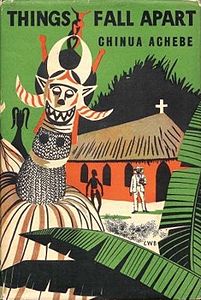

He sends it to a British agent, recommend by his friend Phelps, who gets it to the desk of a publishing house called Heinemann. Once again it meets with skepticism. A novel apparently, from Africa? They seek an informed opinion. A London professor by the name of Donald McRae, the imprint of travel in West Africa still reddening his mind, gives them seven words, all they need, calling it, “The best first novel since the war.” And so Heinemann, the publishing house which sixty years earlier had published Joseph Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus, introduces Chinua Achebe to the world with Things Fall Apart.

And so began one of the century’s great literary careers. As early as 1973 his name began to be mentioned in connection with The Nobel Prize. But when, in 1986, the Nobel committee was finally ready to touch its scepter to the shoulders of an African, the honor fell to Achebe’s compatriot Wole Soyinka. Over the years, three more Africans won, each having stepped through the door Achebe opened. Nadine Gordimer called him “the father of modern African literature.” American laureate Toni Morrison, who wrote an essay on Achebe back in the 1960’s, found his work “liberating in a way nothing had been before.” Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who has been increasingly in the sights of Nobel hounds, owes his emergence onto the world stage directly to Achebe’s championing of his first novel. “Achebe bestrides generations and geographies,” he has said. “Every country in Africa claims him as their own. Some sayings in his novels are quoted frequently as proverbs that contain universal wisdom.”

Still, no Nobel. Reconciling Achebe’s worldwide eminence, which The New York Times has noted “was rivaled only by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Toni Morrison and a handful of others,” with his apparent inability to be sufficiently interesting to Stockholm, has for decades been a mental exercise among his admirers. Arguments coalesce, rather thinly I think, around the Conrad issue. Achebe’s lifelong criticism of this sacred cow of the modern Western canon must, they think, have inoculated him against a Nobel. As if, having gained the respect of those on board that Congo steamer, he should have had the grace to ascend the gangway they had lowered for him. Well, perhaps. Then there is the language question. Even as Things Fall Apart was blazing the trail that over the next few decades would widen into a highway, Achebe was lambasted for writing in the language of the colonizers. With the steady depreciation of the idea of colonialism, attention has begun to fall, quite rightly, on the endangerment of native languages. Achebe may have made Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s career possible, but writing in Gikuyu has made the Kenyan the more ascendant Nobel contender.

Achebe himself didn’t worry much about the Nobel. He had much greater ambitions: “I would be quite satisfied,” he said, “if my novels did no more than teach [African] readers that their past was not one long night of savagery from which the first Europeans, acting on God’s behalf, delivered them.”

Last year Carlos Fuentes deprived the Nobel committee the honor of making him a laureate. Last month it fell to Achebe to do the same.