I.

Four years ago my brother almost died of a bacterial infection. When his roommate found him, what little of him was conscious had been gutted by delirium. As we began to guess that Death, poker-faced to the end, did not have the winning hand, I asked my brother if he wanted me to bring him books. Pure projection on my part. Anyone who desires to live will surely want to read. He must have said yes, or I must have thought he did, because the next day I brought him books to borrow. Because I did not know how to lend him actual strength. However much my brother and I may have wanted to be there for each other, we have not been. Every so often, Extraordinary Circumstance attempts to play matchmaker for us, but as soon as it leaves the room, we drift.

My brother is a serious reader. Strange that we have never been able to make of this more than a passing interest between us, like strangers noticing each other wearing identical shoes. But, once in a while, books make handy offerings. Flouting the daunting impassivity of the vital signs monitor glittering overhead, I laid two books in his hands, one short, one long. The first, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, I had not yet read myself, but I told him Sam had, and had loved it. The second, “one of the best I’ve read in recent years,” was Christopher Unborn. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, avatar of all fecundity, and Carlos Fuentes. I looked for signs of interest, satisfied myself that they were there, then took the books off the bed cover where he’d let them rest and set them on the stand next to his bed, pushing aside cards, flowers, and a teddy bear, given by those who knew him better. As I walked past the nurses’ station towards the elevators it felt good to have left him in the care of these great Latin Americans; I was quite sure the restorative powers of their works far outstripped my own.

I hadn’t so much read Carlos Fuentes’ book as shredded it, paper flung and flying from my canines until every bit had been consumed. The wealth of that book, a literary billionaire if ever there was one, its boggling complexity of thought paired with sheer sensual delight, a voluptuous braininess if you will, would make a powerful infusion, I knew. Enough to raise the three-days dead. Enough for my brother.

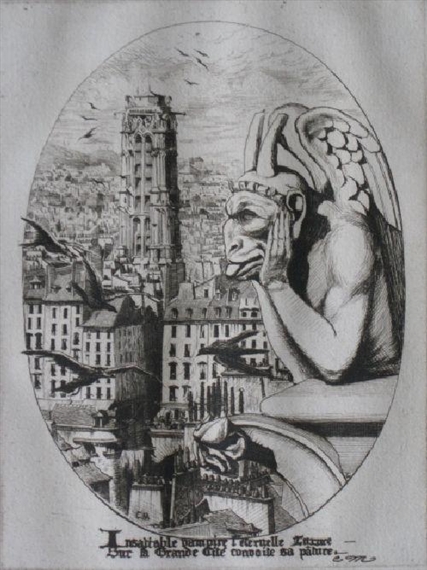

He is angry, my brother. Some of it I understand. Much of it I share. Most of it I would not presume upon. Fuentes, if Unborn signifies, was angry too. His black and flowing anger at what corruption had done to the Mexico he loved must have made his pen hot to the touch. At once knotted and panoramic, Christorpher Unborn – Cristóbal Nonato – with its sinewy orphans, its vamps and dictators, floods and revolutions, mountains of shit and histories of blood, must surely be one of the most coruscating satires in modern fiction. A supreme example of what anger, undammed and channeled, can produce. I wanted that. I wanted that for my brother.

II.

Incredible the first animal that dreamed of another animal. Monstrous the first vertebrate that succeeded in standing on two feet and thus spread terror among the beasts still normally and happily crawling close to the ground through the slime of creation. Astounding the first telephone call, the first boiling water, the first song, the first loincloth.

—Terra Nostra

III.

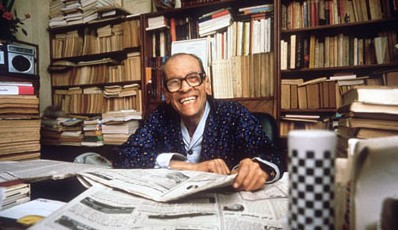

“Sad news: Carlos Fuentes died.”

When Sam’s text came through five days ago I was sitting at my favorite coffee house, immersed in Patrick White: A Life, David Marr’s biography of my current literary addiction. Months had past since my last thought of Fuentes. Not since last October, Nobel season. And before that, not since Sam brought home Destiny and Desire, his last book published in English, from the Border’s dissolution sale. As Christopher Unborn has as its unlikely narrator a fetus waiting to be born on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World, so in this last book, we are addressed from the tongue-biting mouth of a decapitated head. Artemio Cruz narrated his story from the vantage of his last moment in life. Something in Fuentes was drawn to these far boundaries of existence, needed, somehow, to crash them, as if what he had to say could only be said if common understandings were dissolved at the outset. Time, after all, is passing.

Fuentes’ Nobel Prize had been ripening for years in that Northern grove, its luster outshining many of those which dropped before it. Including that of Mario Vargas Llosa. I was dismayed when two years ago the Nobel went to the Peruvian. Not because I thought him undeserving. Only that Fuentes was more deserving. Llosa is, without question, a great writer, but what of his matches the shear myth-making weather system of Terra Nostra, the evocation of the uncanny of Aura, the summation of a history of revolution as found in The Death of Artemio Cruz, the volcanic heart of Christopher Unborn?

Now, Fuentes has died. His Nobel still hangs, no less bright for having never been given. Those tenders of literary reputations in Stockholm won’t touch it. It burns their hands.

IV.

You will never again see those faces you saw in Sonora and Chihuahua, faces you saw sleepy one day, hanging on for dear life, and the next furious, hurling themselves into that struggle devoid of reason or palliatives, into that embrace of men which is broken by other men, into that declaration, here I am and I exist, with you and with you and with you , too, with all hands and all veiled faces: love, strange, common love that wears itself out on itself. You will say it to yourself, because you lived through it and you didn’t understand it as you lived it.

—The Death of Artemio Cruz

V.

My brother has not returned Christopher Unborn. I even asked him to bring it with him when, a few weeks ago, we had dinner together. “I even set it by the door before I came,” he apologized. “No worries,” I said. “Nothing urgent.” As we chewed our restaurant food along with his recent, failed, engagement to a girl who could never have shared in his reading. I don’t know why he hasn’t given it back. I don’t know why he left it at home that night. And since I don’t know, I’m free to imagine. Let Fuentes be with him awhile longer. As long as necessary.

Fuentes? Now more than ever.