“These women are insufferable!” Every day for about two weeks, the same refrain.

“These women are insufferable!” Every day for about two weeks, the same refrain.

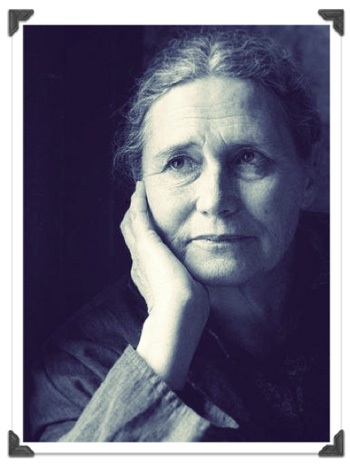

Before October of 2007 neither Sam nor I had read a word of Doris Lessing. We knew her by reputation only: a minor colossus, not in the Proust-Joyce-Mann-Woolf-Faulkner range, but prominent in the Naipaul-Grass-Morrison-Gordimer range, whose work had, by some arguments, wider social impact than any in either range. For years a copy of The Golden Notebook had taken up its blocky space on our shelf, occasionally shifting position one way or another as new books squeezed in around it. Whatever might have seemed forbidding about it – its specs, its status as icon – had long since been mitigated by familiarity, like with the bulky house a few blocks from the street on which I grew up which my childhood cohorts and I delighted in taking for haunted, the possibility of which, somewhere along the line, we lost interest in verifying. But on that October morning, when reporters met her outside her London home as she returned from shopping to inform her she’d won the Nobel Prize and she uttered her now famous “Oh Christ! I couldn’t care less”, Sam decided it was time. He decided to crack The Golden Notebook first.

And quickly decided to make it his last. “These women are insufferable,” he’d moan every twenty pages or so. “Cold. Heartless. Narrow!” Not having read it myself, I nonetheless felt compelled to come to the famous book’s defense. I put it to him that she was breaking new ground. “Maybe she’s showing what can happen to women’s psyches when they decide to not to capitulate to the society that holds them down. In other words, maybe she deliberately drew them to be as you are finding them.”

“But it’s about choices, isn’t it,” he would counter. “These women never really grow or change. Toni Morrison’s characters face profound oppression. But there’s real drama in their choices, with real consequences, and they don’t become narcissistic bitches.”

“A character doesn’t have to be likable for a book to be good.”

“But there has to be something about a character that gives the reader a stake in her fate. These women are just bores.”

“The writing itself?”

“Graceless!”

And so it would go.

My late partner Sam was one of the two or three most serious readers I have ever known. Books were an indelible part of our life as a couple. And yet we read very differently. He entered into a book far more completely from an emotional standpoint than I do. If he was moved, it was a physical experience for him. If he loved a character, it was almost as a lover. He thought about them outside the context of the printed page. I’ll never forget how riled our friend Nathan got when Sam, who was reading Ulysses, said he wondered if Stephen Dedalus brushed his teeth and whether or not he thought about girls. “It’s not in the text!”, Nathan protested. Because his relationship with a book was so intimate, so totally personal, if a writer, such as Doris Lessing, struck him poorly, his refusal to forgive was absolute.

My own relationship to books is, I believe, hardly less personal. But even the books that affect me the most tend to retain about them something of the artifact, an object that can be turned over, sniffed, tasted, examined and wondered about as part of the large world outside my body. This does not make me a better reader than Sam, and it certainly doesn’t mean I’m an “objective” reader, because I don’t believe there is such a person. I might even consider that the bit of distance I keep from the printed page in some ways limits me; Sam’s openness to his own passionate response was part and parcel with the fullness with which he engaged with life. But it does mean that a writer such as Lessing, for whom I, too, will never have much fondness, can remain at least interesting to me.

I’ve now read five of Lessing’s novels (though, strangely, not yet The Golden Notebook), and, have noted that a hard, rather self-involved female protagonist, much as Sam described Anna Wulf, seems to make the rounds to each of them. I was struck by an observation Michiko Kakutani made in her review of Under My Skin (1994), the first installment of Lessing’s autobiography. Responding to a passage in which Lessing discusses her decision to leave her husband and two small children, Kakutani writes:

This matter-of-fact tone informs much of this volume, leaving us with a vivid, if somewhat chilling picture of the author as a self-absorbed and heedless young woman. Ms. Lessing tells us that she was not in love with her first husband, or her second, and that her maternal instincts temporarily “switched off” after the birth of her second child. Again and again, she describes her actions as a mere reflection of the Zeitgeist, a point of view that may illuminate the social dynamic animating so many of her novels, but that also suggests a certain reluctance to assume responsibility for personal choices.

A chilling picture indeed. Lessing’s use of the equivocal virtue of candor to convey what should be a monumentally difficult piece of personal information is fraught. There can be humility in candor, and there can be arrogance. When humility is up, we feel invited to take a look around the subject itself and see complexity. Forgiveness becomes moot because we see ourselves and feel braced by an honoring of our fragile humanity. When it is arrogance, we can feel under assault, and may experience the need to forgive without being sure we have the reserves for it. To say “matter-of-factly” that one walked out of the life of one’s young children, and to style this as zeitgeist-driven, is really no different than self-absolution via “the Devil made me do it.” We sense an attempt to warp the moral universe to one’s own needs. Our response becomes truncated; it’s either “you monster” or “you trailblazer”, and our sense of human possibility becomes thin fare indeed.

I, like Sam, and apparently many others, both among her admirers and her detractors, have noted her rather pedestrian and occasionally leaden prose. “Indigestible,” in the words of one critic. After her Nobel win, American critic Harold Bloom (himself a marvelous windbag of genius) said he found her novels of the last fifteen years to be “unreadable”. I was interested to read in the New York Times tribute that no less a writer than J. M. Coetzee weighed in on this, saying, “Lessing has never been a great stylist — she writes too fast and prunes too lightly for that.”

I, like Sam, and apparently many others, both among her admirers and her detractors, have noted her rather pedestrian and occasionally leaden prose. “Indigestible,” in the words of one critic. After her Nobel win, American critic Harold Bloom (himself a marvelous windbag of genius) said he found her novels of the last fifteen years to be “unreadable”. I was interested to read in the New York Times tribute that no less a writer than J. M. Coetzee weighed in on this, saying, “Lessing has never been a great stylist — she writes too fast and prunes too lightly for that.”

And yet there remains something about Lessing. Her standing as a major writer seems to transcend the writing itself. When she turned her own problematic choices into materials and brought them to bare on her novels the result was nothing less than the clarion call of a new epoch, especially for educated women, and by extension, everyone else. She was, indeed, a zeitgeist prophet. Margaret Atwood put it this way in her tribute in The Guardian:

If there were a Mount Rushmore of 20th-century authors, Doris Lessing would most certainly be carved upon it. Like Adrienne Rich, she was pivotal, situated at the moment when the gates of the gender disparity castle were giving way, and women were faced with increased freedoms and choices, as well as increased challenges.

It is perhaps a touch whimsical to illustrate Lessing’s greatness by invoking that famous piece of gigantic kitsch in the hills of South Dakota. But Atwood’s meaning is clear; in a very real way, at least in the land of literature, there was a “before Lessing” and an “after Lessing”. Virginia Woolf was, by orders of magnitude, the greater writer, but she didn’t write about women’s orgasms. More importantly, she didn’t level her sights directly on a society which, by precluding such discussion, showed its true, imperialistic colors, its dependence for continuance on the enslavement, either emotional or actual, of huge segments of the Earth’s people. Whatever else may be said of the work of Doris Lessing, her vision was necessary and transformative. For this, Sam’s opinion notwithstanding, her honors are merited.