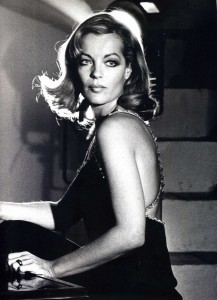

I had the strangest dream last night: The Nobel Prize for Literature was announced, and the winner for 2012 was…Romy Schneider. Lets hear it for 1960’s Euro-glam! You might easily wonder how much time I have spent obsessing about Frau Schneider that her name would elbow through to the fore of my dreadfully overstuffed unconscious. Absolutely none. I assure you. In fact, I had to Wiki her just to remind myself what films I’ve seen her in. While in her too-short life the Austrian-born bombshell made trouble for stiff, bland Tom Tyron in Otto Preminger’s The Cardinal, played Empress Elizabeth of Austria in Lucchino Visconti’s lugubrious Ludwig, and carried on a very public affair with Alain Delon, produce a great work of literature she did not. I could be persuaded that she had an active postcard life, but, beyond that, it is hard to even imagine her in the act of writing. But, in my dream, she had written at least one great novel, praised for its “pervasive melancholy and diaphanous language”. From what neural trash-bin of cliches did I pull this? My first thought upon waking: It should have gone to Fanny Ardant. With her Truffaut background and ability to take Cathrine Deneuve to the floor, she’d have no time for such gauzy tosh. My second thought was a rueful wish that Schneider had actually produced this reputed lachrymose masterpiece. I’d be curious to read it. Though it would, perhaps, be a toss up between that and Simone Signoret’s memoir, Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used To Be.

Thankfully, the choice for the Nobel is not up to my brain stem. It is, rather, up to the brain stems of the five men and women appointed by the Swedish Academy whose job it is each year to dream up a winner. If this sounds irreverent to that illustrious coterie of intellectual curators, consider neuroscience. Because of the work of scientists, who themselves have won Nobels, we know that to make so-called “rational” decisions, our brains must enlist their more antiquated components, those areas in charge of our emotions, desires and anxieties, our knee-jerk reactions, all that was once subsumed by the Freudian id. The separation of reason from un-reason, they tell us, is pure illusion. In a normally functioning brain, the cortex weighs options, puts forth its arguments, assembles its narratives, but at the moment of choice, something primal, emotional, reptilian, must be satisfied. What we decide to do with our money, who we decide to sit next to on the bus, or vote for, or flirt with, or flee, who, what, how, and where we decide to worship, or read, unless we draw on the lizardish parts of our brains – those parts connected to our dreams – we are left in a purgatory of indecision.

When the announcement comes, the head secretary will issue a pithy statement, summarizing the committee’s rationale. The new laureate may “Give voice to an experience as yet un-heard on the World stage”, or use language to “limn the boundaries of the sayable.” But, in his effort to make their choice make sense to us, he won’t tell us the half of what went into it. To wit, what lights their little Nordic fires.

Whatever conversations I might have with my analyst about my “Romy Schneider wins the Nobel Prize” dream, the best part of it is the sublime joke of it, that is, its unpremeditated murder of expectation. Whether we grouse or whoop, we all secretly love it when this happens. Our brain stems light up, we become alert, our bodies vibrate. My waking brain will forever keep Romy Schneider from her Nobel Prize. But there is something in the names of each of the men and women I do place on my personal list of contenders that lights the same spark of delight I had upon waking this morning, and realizing that something rather fabulous had happened.

So, in the next few weeks, think kind thoughts for the Swedish five, as they lay their heads down each night on their impeccably laundered pillows, that their brain stems send them wild dreams, and that when they wake to hold their conclave, they remember the delight.

My Personal Long List:

In the mean time, here is my long list for this year. Sometime before the big announcement, I’ll share my short list. Read through it. If there is someone I’ve named at whom your own limbic system shudders, by all means say so. Likewise if you are in agreement about any of these writers, let me know. But, best of all, if there is someone absent from this list who you feel must be included, don’t remain selfishly silent. Tell us who you would dream up as a winner.

1. Chinua Achebe (Nigeria)

2. Antonio Lobo Antunes (Portugal)

3. Margaret Atwood (Canada)

4. Bei Dao (China)

5. Juan Goytisolo (Spain)

6. Ismail Kadare (Albania)

7. György Konrad (Hungary)

8. László Krasznahorkai (Hungary)

9. Milan Kundera (Czech Republic/ France)

10. Cormac McCarthy (United States)

11. Alice Munro (Canada)

12. Les Murray (Australia)

13. Cees Nooteboom (Netherlands)

14. Amos Oz (Israel)

15. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya (Russia)

16. Philip Roth (United States)

17. Salman Rushdie (Great Britain)

18. Tom Stoppard (Great Britian)

19. William Trevor (Ireland)

20. Michel Tournier (France)

It’d be hard to argue against any of those writers winning the prize. If they stood a chance of locating him I’d recommend Guatemalan Rodrigo Rey Rosa to the committee. From what I understand he frequently travels alone in remote areas and lives part of the time way out in the middle of the Peten. But his body of work is so peculiar, diverse, and each individual novel is so finely crafted around it’s subject matter (or the other way around?), which can range from the biggest, darkest aspects of life and history to simple tales of love (or perhaps not so simple? Oddly hard to say), that I think he’d be an ideal candidate.

In the meantime, Nicanor Parra thinks he deserves the Nobel Prize for Reading. I’d be inclined to grant it to him:

“The Nobel Prize for Reading

should be awarded to me

I am the ideal reader,

I read everything I get my hands on:

I read street names

and neon signs

bathroom walls

and new price-lists

the police news,

projections for the Derby

and license plates

for a person like me

the word is something holy

members of the jury

what would I gain by lying

as a reader, I’m relentless

I read everything – I don’t even skip

the classifieds

of course these days I don’t read much

I simply don’t have the time

But – oh man – what I have read

that’s why I am asking you to give me

the Nobel Prize for Reading

as soon as impossible”

I am a huge fan of William Trevor. If literature is, as I believe, the study of the human, Trevor is one of its best teachers. In a simple, yet intelligent prose he introduces us to characters with ordinary lives, characters that are so well developed we feel we know what they might do in a given situation. These characters that we might find in our neighborhoods are like us, or people we know, in so many ways that when we learn the one peculiar thing about them it is all the more unsettling. How often do we hear, “he seemed like a nice guy, we would have never guessed he was capable of that,” or how often have we wondered why we didn’t see some unsavory aspect to someone we thought we could trust? If you ever feel you are alone in dealing with some sort of pain or loss, or a bit embarrassed or disappointed in a loved one Trevor will teach you how universal your experience really is.

I don’t think Rushdie will receive the Nobel for fear of inflaming extremists.

Listen to this, Wendy:

“After the funeral the hiatus that tragedy brought takes a different form. Thaddeus has stood and knelt in the church of St. Nicholas, has heard his wife called good, the word he himself gave to a clergyman he has known all his life.”

The first two sentences of Death in Summer, Trevor’s short novel from 1998. Unpacking the wealth of information carried by these few words leaves us dazzled, and measurably richer. There are no greater living writers in English. I have a fantasy of a rare joint Nobel going to Trever and Munro, twin pillars of the art of the short story.

I’ve read 18 of those authors, and agree on any. I do think Pynchon, in America, has produced three masterpieces which are exciting and riveting reading experiences {Mason and Dixon, Gravity’s Rainbow, V ].

Perhaps unknown in the Nobel circles are Ron Hanson and Marylyn Robinson, who write beautifully and explore themes to a great depth, something I can not say for Roth.

Given Tolstoy lost out we can only hope no such figure is to feel the lash of ignorance again.

Hello Michael. I love it that you mentioned Marilynn Robinson. She is one of the subtlest, strongest writers America has – and will almost certainly never win a Nobel Prize. On of my favorite writers in the same category – that is, a writer as good as it gets, but uninteresting to Stockholm – is Annie Dillard. It brings up a the endlessly fascinating question of just what the Nobel committee reads for.

You are clearly a member of the great army of serious readers who deeply admire Thomas Pynchon. I confess I have only read The Crying of Lot 49, and was not warmed by it. I recognize this as my own lack, and believe, quite willingly, that he is as great as those who love his work say he is.

I must, however, respectfully disagree with your dismissal of Philip Roth. Since he is not likely to win on Thursday, perhaps I will do a post on him, explaining why I believe he is one of America’s three or four great living masters.

All the best to you, Michael. I look forward to hearing from you again.

Until Thursday…