Everyone wants a Nobel Prize. Chilean poet Nicanor Parra feels he should get the “Nobel Prize for Reading”. How many aspiring writers feel they have the “Nobel Prize for Potential” in the bag? Nobel dreams arise from feelings of being unseen. One goggles out of one’s cranium at the wider world and sees the attention of those whose attention seems to matter being directed elsewhere, towards others, and one feels cut adrift, less than fully real, even, perhaps, mortally threatened. What people are really wanting when they want a Nobel Prize is to be seen and validated. It’s part of the human legacy to feel, somewhere along the line, unappreciated, misunderstood, not fully recognized. But for some, for whatever reason, the feeling carries an especially strong charge, giving rise to the sense that only something “ultimate” can break it. Winning a Nobel Prize means being seen, and validated, ultimately.

Everyone wants a Nobel Prize. Chilean poet Nicanor Parra feels he should get the “Nobel Prize for Reading”. How many aspiring writers feel they have the “Nobel Prize for Potential” in the bag? Nobel dreams arise from feelings of being unseen. One goggles out of one’s cranium at the wider world and sees the attention of those whose attention seems to matter being directed elsewhere, towards others, and one feels cut adrift, less than fully real, even, perhaps, mortally threatened. What people are really wanting when they want a Nobel Prize is to be seen and validated. It’s part of the human legacy to feel, somewhere along the line, unappreciated, misunderstood, not fully recognized. But for some, for whatever reason, the feeling carries an especially strong charge, giving rise to the sense that only something “ultimate” can break it. Winning a Nobel Prize means being seen, and validated, ultimately.

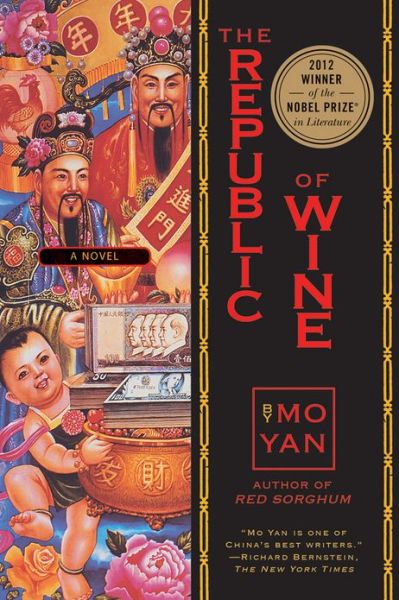

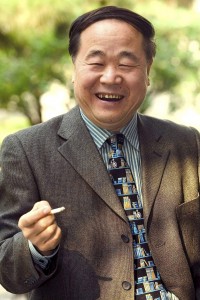

What goes for individuals can also go for whole cultures. Last October, The People’s Republic of China scored, if not its first Nobel Prize, then the first it can make use of in its rambunctious, somewhat hysterical pursuit of validation. Novelist Mo Yan’s win means that China can now punch the air over its invitation onto the cultural playing field. The Western cultural playing field, that is. The power it currently holds is based, in part, on their choice to match or surpass the shots the West had called. “About time, a Nobel,” said the regime.

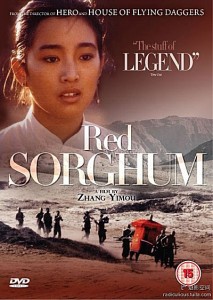

To prolong the afterglow, the Chinese government has invested the equivalent of 110 million dollars to transform Mo’s hometown, the village of Ping’an, a backwater of eight hundred souls in the province of Shandong, into a theme park, the “Mo Yan Culture Experience Zone”. In a nod to Mo Yan’s famous novel Red Sorghum, the government has also mandated the cultivation, “by real peasants”, of 1,600 acres of sorghum, a now useless crop that hasn’t been planted in decades. I strain to imagine an equivalent response anywhere. Imagine the United States congress pushing through a bill to create a William Faulkner theme park in rural Mississippi, exhibiting the mentally impaired, incestuously conceived, and the suicidal, skulking about movie set mansions, with matches, while a near-by cotton field is tended by real free blacks.

Because his fiction often takes on social ills and petty government corruption, many readers see Mo Yan as a gadfly biting the ears of the regime. He has, himself, made much of being a critic of the system “from within the system.” This could explain why his books sing with something of the system’s nasality. With his sprawling historical revisions, incorporation of fantastical elements, and adolescent good-naturedness about sex and violence, he has become an exponent of a what appears to be a dominant strain of the modern Chinese aesthetic sensibility. It is, in essence, a romantic sensibility, rife with exceptionalism and teleological imperative, which hog-ties historical fact against the demands of operatic myth making. As in Romanticism’s more bombastic manifestations, it has little to do with self-understanding and much to do with theatrical projection. For China, the audience for this theater is the rest of the world, with box seats for the First World West. Its stage-managed ploy to be seen and validated by this audience has often resulted in an aggressive tawdriness. Witness the teenaged neon-lit skylines of their millennia-old metropolises. Witness the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a veritable tribal orgasm of overweening muchness. The Three Gorges Dam, whatever its state-proclaimed justification, is, first and foremost, an expression of defiant gigantism, more exhibit than solution. If Mo Yan sometimes criticizes this China, he does so in a prose which this China understands. Now, his books, too, along with his very celebrity, have become exhibits.

In Mo Yan’s 1992 novel, The Republic of Wine, the central government has dispatched special investigator Ding Gao’er to a district called “Liquorland” where he is charged with getting to the bottom of rumors about a decadent culinary practice involving the braising of human baby boys in red sauce. Upon arrival, he is invited to a banquet in his honor, where, after being forced by cultural mores to drink himself blind, he is served what appears to be the dish in question. He is appropriately horrified. The officials hosting the banquet try to calm him, explaining how valuable this dish has been to the region.

In Mo Yan’s 1992 novel, The Republic of Wine, the central government has dispatched special investigator Ding Gao’er to a district called “Liquorland” where he is charged with getting to the bottom of rumors about a decadent culinary practice involving the braising of human baby boys in red sauce. Upon arrival, he is invited to a banquet in his honor, where, after being forced by cultural mores to drink himself blind, he is served what appears to be the dish in question. He is appropriately horrified. The officials hosting the banquet try to calm him, explaining how valuable this dish has been to the region.

‘This is a famous dish in these parts… It’s called Stork Delivering a Son. We serve it to visiting dignitaries. It’s a dish they won’t forget for as long as they live, one that has drawn nothing but praise. We’ve earned a lot of convertible currency for the nation by serving it to our most honored guests.’ (75)

Ding is unpersuaded. In drunken protest, he pulls out his gun and shoots the head off this “incredibly fragrant little boy.”

The drive for caché with the West is even more explicit in a scene depicting a cooking lesson given by a master chef to a group of anxious culinary students. She tells them,

‘As long as you can command the skill of cooking meat boys you’ll never have to worry about a thing, no matter where you go. Don’t you all want to go abroad? So long as you can handle this superior dish, it’s as good as holding a permanent visa in your hand. You can conquer the foreigners, be they Yanks, Krauts, or whatever.” (224)

The comment is slapdash; nowhere else in the novel is it suggested that outside interest has made a local instance of cannibalism exportable. But Mo is being colorful, and a tidy argument would mute his vivid palette.

Ding Gao’er is less a character than a type, recognizable from earliest films noir: the washed-up randy detective, full of posture, and pitiful. The target of his investigation is a local party leader named Diamond Jin, whose godlike charisma goofily stems from his ability to hold his liquor by the apparent swimming pool-full. Such gifts obtain in Liquorland. Ding gets into a made-to-order mess by falling for Diamond’s chip-shouldering, truck-driving girlfriend, who essentially rapes him for blackmail. The final showdown – not with Diamond Jin, but with the girlfriend, as by the end of his story he has completely abandoned the investigation for which he was hired – occurs in a popular watering hole called the Yichi Tavern, owned by a toad-like dwarf named Yu Yichi, able to walk on ceilings, and whose goal, well within sight, is to sleep with every beautiful girl in Liquorland. By the time Ding’s story ends, at the bottom of an open-air privy, where, in retrospect, it had been heading all along, he has become the novel’s only confirmed murderer.

I refer to Ding Gao’er’s story to distinguish it from the two other narrative lines of the novel. The second takes the form of an epistolary exchange between a famous novelist named Mo Yan, who is writing a book fortuitously called The Republic of Wine, and an aspiring young writer named Li Yidou. Mo Yan bears a striking resemblance to the author of the book in hand: overweight, a Kung fu novel aficionado, with a novel called Red Sorghum already under his belt, which – he’s understandably proud of this – was made into a successful movie by the famous director, Zhang Yimou. He is demure about his reputation: “I have no grounding in literary theory and hardly any ability to appreciate art,” he writes. “Any song and dance from me would be pointless.”

I refer to Ding Gao’er’s story to distinguish it from the two other narrative lines of the novel. The second takes the form of an epistolary exchange between a famous novelist named Mo Yan, who is writing a book fortuitously called The Republic of Wine, and an aspiring young writer named Li Yidou. Mo Yan bears a striking resemblance to the author of the book in hand: overweight, a Kung fu novel aficionado, with a novel called Red Sorghum already under his belt, which – he’s understandably proud of this – was made into a successful movie by the famous director, Zhang Yimou. He is demure about his reputation: “I have no grounding in literary theory and hardly any ability to appreciate art,” he writes. “Any song and dance from me would be pointless.”

Li Yidou lives in Liquorville, where he writes his stories while studying for his Ph.D. in – can you guess? – “liquor studies.” Mo Yan is suitably impressed. “I envy you more than is probably good for me,” he writes.

If I were a doctor of liquor studies, I doubt I’d waste my time writing novels. In China, which reeks of liquor, can there be any endeavor with greater promise or a brighter future than the study of liquor, any field that bestows more abundant benefits? In the past, it was said that ‘in books there are castles of gold, in books there are casks of grain, in books there are beautiful women.’ But the almanacs of old had their shortcomings, and the word ‘liquor’ would have worked better than ‘books.’

Despite such coyness, he does offer advice, which mostly involves complimenting the idealistic young man on his prodigious imagination, and suggesting ways to make the stories attractive to a state-sponsored literary rag called Citizen’s Literature.

The stories themselves comprise the third narrative line of the novel. The first few stories address the same nasty business of the meat boys under investigation by Mo Yan’s Ding Gao’er. Among Li Yidou’s recurring characters is a precocious toddler who stages an escape among his fellow toddlers being held in waiting at the culinary institute. In other stories, the same figure morphs into an adolescent boy with scales instead of skin, a kind of trickster making trouble for the government officials. One story recounts how Li’s father-in-law, a respected professor at the Brewer’s college, leaves behind civilization to research the phenomenon of “ape liquor”, wine made by great apes who throw fruit into a natural stone cistern where it ferments, reputed to be the finest liquor in the world. He shares with Mo Yan the character Yu Yichi, the dwarf who owns the famous Liquorville tavern where Ding Gao’er makes his final descent. In keeping with the novel’s gustatory theme, one of the dishes he describes being served at the tavern consists of the genitalia of a male and a female donkey arranged just so on a plate and given the appellation, “Dragon and Phoenix Lucky Together”. The best of Li’s stories and the best writing in the book, is about his mother-in-law, with whom he is erotically fixated, who, in her youth, accompanied her father and uncles to remote caves by the ocean where they harvested, at tremendous, even tragic, personal risk, the swallow’s nests so in demand by China’s most expensive restaurants.

The Republic of Wine feels chaotic. Just what Mo Yan hopes his readers will pull from the chaos seems unclear. His rather broad-stroke metaphor – local government officials sanctioning eating the male children of their own people – is clearly intended to be subversive. That this novel was initially refused publication in China is not surprising. But neither is it surprising that, after the release of a Taiwanese edition, its attributes, we’ll say – I hesitate calling them merits – were reconsidered. The novel, it turns out, actually works in The Party’s favor: In Mo Yan’s fictional country, corruption lies, not in Beijing, with a government known for violent suppression of the populous (the Tiananmen Square Protests had occurred just three years earlier) but in the outposts, where local party leaders surreptitiously practice a gruesome caricature of capitalistic hedonism. While seeming to decry florid abuses of power, it, in fact, leaves China’s central government unscathed and heart of the system remains pure. Approving such a work looks good for the regime, and Mo Yan gets to play both sides. Or so it seems.

One thing I can say unequivocally after reading this novel is that I find the Nobel Committee’s reference to Garcia Marquez in their citation incredible: Lots of writers include fantastical elements in their novels who neither merit nor require a Garcia Marquez pin. In the case of Mo Yan, sentence by sensibility, there is no less apt a comparison. The Colombian master is an infinitely more careful, more painstaking, writer. His fantasy all signifies, while Mo’s frequently seems gratuitous, as if he thought of it thirty seconds before writing it. As with his use of sex and violence, the flights of fancy, what the Nobel citation calls “hallucinatory realism”, seem included only to raise the decibel level, and a kind of puerile hysteria, like a room full of second graders doing the underpants dance. I am surprised at The Committee’s superficial reading, of both authors.

Equally incredible is The Washington Post’s endorsement of this novel, invoking Gorky and Solzhenitsyn. In an article called a “The Diseased Language of Mo Yan”, which appeared in The Kenyon Review, Anna Sun, a professor of Sociology and Asian Studies at Kenyon, contrasts Mo Yan with the greatest writers who have tackled the harshest social ills, suggesting that Mo lacks “aesthetic conviction.” She writes, “The effect of Mo Yan’s work is not illumination through skilled and controlled exploitation, but disorientation and frustration due to his lack of coherent aesthetic consideration. There is no light shining on the chaotic reality of Mo Yan’s hallucinatory world.” She goes after the writing itself, demonstrating how it fails to rise above “Mao-ti”, or “Mao-speak”‘ a language which survived the Cultural Revolution, when the state forced literature to break with its long literary heritage.

Open any page, and one is treated to a jumble of words that juxtaposes rural vernacular, clichéd socialist rhetoric, and literary affectation. It is broken, profane, appalling, and artificial; it is shockingly banal. The language of Mo Yan is repetitive, predictable, coarse, and mostly devoid of aesthetic value. The English translations of Mo Yan’s novels, especially by the excellent Howard Goldblatt, are in fact superior to the original in their aesthetic unity and sureness. The blurb for The Republic of Wine from Washington Post says: “Goldblatt’s translation renders Mo Yan’s shimmering poetry and brutal realism as work akin to that of Gorky and Solzhenitsyn.” But in fact, only the “brutal realism” is Mo Yan’s; the “shimmering poetry” comes from a brilliant translator’s work.

Even with Goldblatt’s heroic efforts, I, for one, experienced more shuddering than shimmering, at bald clichés and flat, unlayered prose.

Calling Mo Yan’s Nobel Prize “a catastrophe”, will likely prove one of Herta Müller’s most enduring public statements. The Swedish Academy’s decision to honor a writer who has refused to support dissident writers, and who has publicly attested to the usefulness of censorship, is, to her, an abomination. Yet, Mo Yan himself insists that his win is “a literature victory, not a political victory.” Echoing his position, the Nobel Committee had its perennial protestation, about the non-political, purely literary focus of the award all primed and ready to spray over the arguments of the expected detractors. Far more expert readers than me have persuasively argued the impossibility of such a clear separation of art from ideology, and it seems to me that Mo Yan would do well to invite the political foment, if only to distract readers from his actual writing.

Still, if read as a cultural artifact, The Republic of Wine holds a certain fascination. And I’m ready and willing to concede that my grimaced reading may, to some extent, be a cultural mis-reading. Clearly, his wild popularity in China avers that he has seen something compelling about China’s moment, and validated the experience of its people, or some important and unavoidable aspect of it. And who am I to say the favor shouldn’t be returned. While I find his political choices disturbing, to say the least, I cannot join those who cry that Stockholm should, for that reason alone, disinvite him from its table. If the artistry holds up, nothing more need be said. To me, it doesn’t. But then, he’s speaking for a country that would make a theme park out of his celebrity.

Still, if read as a cultural artifact, The Republic of Wine holds a certain fascination. And I’m ready and willing to concede that my grimaced reading may, to some extent, be a cultural mis-reading. Clearly, his wild popularity in China avers that he has seen something compelling about China’s moment, and validated the experience of its people, or some important and unavoidable aspect of it. And who am I to say the favor shouldn’t be returned. While I find his political choices disturbing, to say the least, I cannot join those who cry that Stockholm should, for that reason alone, disinvite him from its table. If the artistry holds up, nothing more need be said. To me, it doesn’t. But then, he’s speaking for a country that would make a theme park out of his celebrity.

On-line references (Each of these, especially the second and third, are worth reading):

http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/chapter-and-verse/2012/1025/China-transforms-Nobel-Prize-winner-s-hometown-into-a-theme-park

http://www.chinafile.com/politics-and-chinese-language

http://www.kenyonreview.org/kr-online-issue/2012-fall/selections/anna-sun-656342/