I. THE BOOK: GOD APPEARS IN A GOB OF SPITTLE

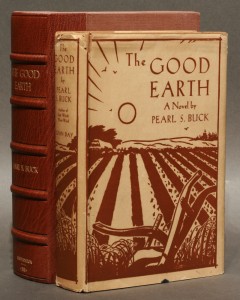

It is hardly a spoiler to say that on page 508 of Patrick White’s novel The Tree of Man Stan Parker dies. One gathers from the opening pages, in which we find the young Stan Parker establishing himself as a pin-point of humanity in the vast Australian bush, that this is going to be “that kind of a book”. One could even suspect it from the title itself, proclaiming, as it does, the novel’s encompassing intentions with perilously grand echoes: The Descent of Man, The Tree of Life, The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, Man’s Fate, Man’s Hope, The World Tree, The Rise of Man, The Fall, etc.. No question that we are going to be reading through the full gamut, life, death, and all the rest. By the time we turn the last pages, having lived with Stan Parker, his wife, Amy, and their children, Ray and Thelma, through fire, flood, griefs, infidelity, failures and quiet triumphs, and, yes, Stan’s death, that potentially burdensome title, we find, has long since shed all grandiosity, and become merely apt.

Stan Parker has been called Patrick White’s “first good man”. David Marr, White’s biographer, records his struggles to create him: “The greatest technical difficulty White faced, one which drove him to rages and left him sitting, at times ‘three days over just one sentence’ was the challenge of making goodness live and breathe on the page. ‘I’m not a good person,’ White often confessed to his friends. ‘But I know goodness.'” Stan Parker is stubborn and a bit of a fatalist, like White himself. He is practical, strong of body, taciturn, with a great, uncharted continent of poetry lost somewhere inside of him. This subterranean spiritual thirst sends out signal flares in fragile moments, as when he takes Ray, with whom he has spent the years leading up to the boy’s puppy-killing adolescence inadvertently constructing a great edifice of relational failure, into the bush, in hopes that the vast, open distances will do for his son what it always does for him.

Stan intuits God, without ever naming God, in the elements. On a hot night, after Amy, has gone to bed, he remains outside, waiting for a storm to break. When it does, he is, at first, exultant.

But as the storm increased, his flesh had doubts, and he began to experience humility. The lightning, which could have struck open basalt, had, it seemed, the power to open souls. It was obvious in the yellow flash that something like this had happened, the flesh had slipped from his bones, and the light was shining in his cavernous skull.

Yet, for all the intimations, God remains elusive. Only at the end, minutes before his death, does Stan receive his revelation. He is sitting in a chair, old and failing, amidst the trees in the yard outside his home, where he is accosted by an earnest young man aflame with the Gospel. God, the young man believes, has saved him from a life of women and alcohol. Such conversions crave ratification through the conversions of others, and Stan Parker has been elected. Which means that this most private moment at which his life has, at last, arrived, is threatened by farce. During this encounter, Stan relieves himself of phlegm:

Then the old man, who had been cornered long enough, saw, through perversity perhaps, but with his own eyes. He was illuminated.

He pointed with his stick at the gob of spittle.

“That is God,” he said.

As it lay glittering intensely and personally on the ground.

Stan is not being impertinent. He is responding to a great unveiling. The bewildered young man departs, leaving behind some tracts which he hopes will finish the job he, and of course the Holy Spirit, have begun, while Stan continues to stare at the spittle. Only now, a “jewel”.

A great tenderness of understanding rose in his chest. Even the most obscure, the most sickening incidents of his life were made clear. In that light. How long will they leave me like this, he wondered, in peace and understanding.

The “gob of spittle” passage is famous in Australian literature. It is one of the very few overtly religious moments in what is a deeply religious novel. White’s God, when finally called forth, is, as we see, viscous. What’s more, this God has emerged from Stan himself. Quite literally. In all of White’s work, and in this book in particular, it is only when his characters cease resisting their messy, humbling, secreting bodies, and the often ramshackle lives through which those bodies stumble, that they encounter what they had always believed lay beyond themselves. What they encounter is no less transcendent for this, no less luminous. It is a difficult truth. But then, Patrick White is known as a “difficult” writer. Difficult, too, because he uses a richly allusive, subtly symbolic language to coax his reader into a parallel awareness. Sentence by sentence, phrase by phrase, White nudges his reader awake, quietly drawing attention to something just off the page, or behind it. Listen to how White evokes Stan, on that last afternoon, sitting:

That afternoon the old man’s chair had been put on the grass at the back, which was quite dead-looking from the touch of winter. Out there at the back, the grass, you could hardly call it a lawn, had formed a circle in the shrubs and trees which the old woman had not so much planted as stuck in during her lifetime. There was little of design in the garden originally, though one had formed out of the wilderness. It was perfectly obvious that the man was seated at the heart of it, and from this heart the trees radiated, with grave movements of life, and beyond them the sweep of a vegetable garden, which had gone to weed during the months of the man’s illness, presented the austere skeletons of cabbages and the wands of onion seed. All was circumference to the centre, and beyond that the worlds of other circles, whether crescent of purple villas or the bare patches of earth, on which rabbits sat and observed some abstract spectacle for minutes on end, in a paddock not yet built upon. The last circle but one was the cold and golden bowl of winter, enclosing all that was visible and material, and at which the man would blink from time to time, out of his watery eyes, unequal to the effort of realizing he was the centre of it.

I quote at length because White does a better job than I could ever do of summation. We have come to know this rangy garden, these trees. By drawing attention, at the novel’s end, to its inception as a kind of horticultural flailing, and its subsequent emergent design, White invites us to consider at least two layers of meaning beyond the the physical. First, there is the life of this couple, more like the garden described than the garden itself. Notice that here Amy is named “the old woman”. Throughout the book, at intervals, Stan and Amy are stripped of their given names and called simply, “the man”, “the woman”, rendering them at once mythic and fragile. We’ve met them before, most memorably in The Book of Genesis. We watch these two ordinary, unformed, people, grope their way toward each other, generally missing each other by a mile. We watch as they try, and fail, to be the parents their children need. We watch Amy become possessive, while Stan grows ever more distant. We watch their erotic lives travel along incompatible arcs of meaning. The flood they survive and the fire they survive, leave scars on their souls far more lasting than those left on the land on which they survive. And that land, on which they were the first to settle, will not long bear up under the ugly banality of urban encroachment. Along the way they learn that death is always a violence, regardless of its means, and that death can mean something quite other than the demise of the body. As they approach the end of their great meander, not far in miles, but metaphysically epic, they find they have arrived at a life. Its been going on all along, of course. They can look across it now, find its design, and a kind of undeclared grace. Through their story, White draws our attention to a process, the mystery of creation itself. What wasn’t, now is, simply for something having been “stuck in” along the way. It is as if, at the end of the novel, we are witnesses to its birth.

And how about all those circles. This passage’s most obvious antecedent is the famous final paragraph of The Dead, in which Joyce lifts his lens to ever more encompassing circles of snowfall. In White’s homage, Stan sits at the heart of a veritable mandala: a circle of shrubs and trees first, then the vegetable garden, then the paddocks, and, the last but one, the “cold and golden bowl of winter.” Like a Hasid, White refuses to name the final circle. And yet, it is into this circle that all is, finally, subsumed.

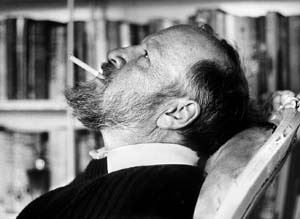

II. THE BACKGROUND: THE REPATRIATED PATRICK WHITE LANDS ON HIS BEHIND

White might never have written The Tree of Man. The poor reception, in Australia, of his previous novel, the brilliant The Aunt’s Story, had all but disposed him never to write again. But then, Australia itself began to encroach upon his always negligible peace of mind. In his autobiographical essay, “The Prodigal Son”, he writes about the inception of The Tree of Man:

Then, suddenly, I began to grow discontented. Perhaps, in spite of Australian critics, writing novels was the only thing I could do with any degree of success; even my half-failures were some justification of an otherwise meaningless life. Returning sentimentally to a country I had left in my youth, what had I really found: Was there anything to prevent me packing my bag and leaving…? Bitterly I had to admit, no. In all directions stretched the Great Australian Emptiness, in which the mind is the least of possessions, in which the rich man is the important man, in which the schoolmaster and the journalist rule what intellectual roost there is, in which beautiful youths and girls stare at life through blind blue eyes, in which human teeth fall like autumn leaves, the buttocks of cars grow hourly glassier, food means cake and steak, muscles prevail, and the march of material ugliness does not raise a quiver from the average nerves.

It was the exaltation of the ‘average’ that made me panic most, and in this frame of mind, in spite of myself, I began to conceive another novel. Because the void I had to fill was immense, I wanted to try to suggest in this book every possible aspect of life, through the lives of an ordinary man and woman. But at the same time I wanted to discover the extraordinary behind the ordinary, the mystery and the poetry which alone could make bearable the lives of such people, and incidentally, my own life since my return.

This discontent, and the urgency to ameliorate it through writing, had a background which he did not reveal until late in his life, when age had, if anything, sharpened his powers of ruthless self-observation. In his memoir, Flaws in the Glass, he recounts a Damascene moment which, like Stan’s final transfiguration, was at once intensely personal and catalyzed by farce. Actually, in White’s case, slapstick: White and his partner, Manoly Lascaris, were raising Schnauzers on a six-acre farm on the outskirts of Sydney. He hadn’t written anything for nearly seven years, and had grown used to it. A few days before Christmas 1951, a frail but kicking faith broke through while feeding the dogs in a downpour…

During what seemed like months of rain I was carrying a trayload of food to a wormy litter of pups down at the kennels when I slipped and fell on my back, dog dishes shooting in all directions. I lay where I had fallen, half-blinded by rain, under a pale sky, cursing through watery lips a god in whom I did not believe. I began laughing finally, at my own helplessness and hopelessness, in the mud and the stench from my filthy old oilskin.

It was the turning point. My disbelief appeared as farcical as my fall. At that moment I was truly humbled.

…and from this faith, the need to carve out a place for it in a world that seemed at odds with it. From the opening sentences of The Tree of Man, we hear him wrestling to draw forth “the extraordinary behind the ordinary”, what Annie Dillard calls “Holy the Firm”, a mystical substance on which the physical world is made, but which is, itself, in touch with God. On every page you can hear White explaining to himself that Advent-season ass-plant in the mud, smeared with what he could no longer resist.

Worse things, by far, have taken root in the mud. This is a very great book. I hope you read it.

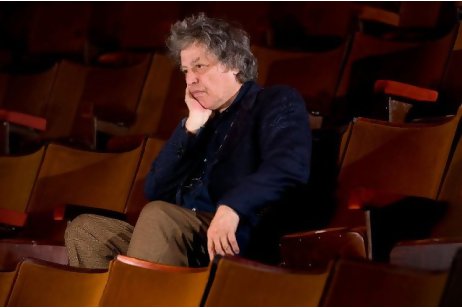

III. AN INTERVIEW WITH WHITE’S BIOGRAPHER, DAVID MARR: “THE LIFE AND FAITH OF PATRICK WHITE”