The woods in Robert Frost’s mind were particularly snowy on that day in 1938 when Pearl Buck won the Nobel Prize. “If she can get it, anyone can,” he famously declaimed in rather artless iambic tetrameter, stating more succinctly than anyone to follow an opinion which has ever since dogged both the author and the orchard keepers of that peculiar Northern grove of literary reputations. Buck herself knew what a problematic choice she was, and the weight of this knowledge lead her to a gracious humility (of which she evidently cured herself in later years). In an interview with the New York Times she bowed to Theodore Dreiser as the more deserving author and acknowledged feeling “diffident in accepting the award.” In her acceptance speech she said, “I can only hope that the many books which I have yet to write will be in some mearsure a worthier acknowledgment than I can make tonight.” It all must have been a bit much for her; as Peter Conn, her most eloquent contemporary apologist, points out, she went from being unpublished and unknown to winning the Nobel Prize in less than ten years. It strikes me as both touching and a little melancholy that this most popular of American writers felt compelled to make public statements like crossed index fingers raised against a tide of negative opinion.

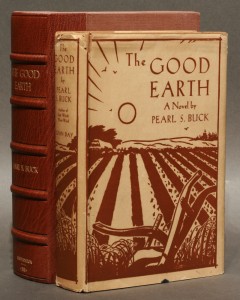

Of course, not all opinion was negative. When The Good Earth, her famous tale of a Chinese farmer’s perseverance in the face of crushing odds, was published in 1931, it found an acutely well-primed audience. America was plummeting down the steep slopes of the Great Depression. The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s monumental contribution to the literature of perseverance, was not published until 1939, which means that The Good Earth was the brightest literary beacon on the horizon for most of America’s darkest hour since the Civil War.

Of course, not all opinion was negative. When The Good Earth, her famous tale of a Chinese farmer’s perseverance in the face of crushing odds, was published in 1931, it found an acutely well-primed audience. America was plummeting down the steep slopes of the Great Depression. The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s monumental contribution to the literature of perseverance, was not published until 1939, which means that The Good Earth was the brightest literary beacon on the horizon for most of America’s darkest hour since the Civil War.

Her admirers, from the Nobel Committee to the Chinese American author, Maxine Hong Kingston, have lauded her for being the first writer to bring China to the attention of the West. Kang Liao, author of Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Bridge Across the Pacific, goes further, saying that her books were valuable, not only to Americans, but “to us Chinese in learning about ourselves and particularly about the majority of the Chinese people, the peasants and farmers of whom we had little truthful and realistic representation in literature until after the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976.” Historian James Thomson rather more extravagantly called her “the most influential Westerner to write about China since thirteenth century Marco Polo.”

But out of the chorus of her defenders’s voices, variously pitched – earnest, sometimes aggrieved, sometimes rather missionary – a curious lacuna arises: They can’t quite get around to praising the writing itself. Some make a virtue of this by disowning the problem. In an essay cagily entitled “Who’s Afraid of Pearl S. Buck”, Jane Rabb takes up her sling against literary academics, a perennially heroic enterprise, and not without some justification. She writes, “After the Second World War, literary scholars favored the New Criticism, a close analysis of texts independent of history and biography, an approach no more suited to Buck’s writing than its convoluted successors, Structuralism and Deconstructionism.” American educator, historian, and literary critic Oscar Cargill charged that, “To reflective Americans outside the [literary] fraternity… the prize seemed  well given as a reminder that pure aestheticism is not everything in letters. If the standard of her work was not so uniformly high as that of a few other craftsmen, what she wrote had universal appeal and a comprehensibility not too frequently matched.” That “few other craftsmen” comes across as a pricy concession paid for on credit. Cargill was the author of notable books on both Eugene O’Neill and Henry James, a Nobel laureate and a writer who should have been, neither noted for their “appeal and comprehensibility”. He clearly understood Buck’s shortcomings and all but says “Let’s not go there.”

well given as a reminder that pure aestheticism is not everything in letters. If the standard of her work was not so uniformly high as that of a few other craftsmen, what she wrote had universal appeal and a comprehensibility not too frequently matched.” That “few other craftsmen” comes across as a pricy concession paid for on credit. Cargill was the author of notable books on both Eugene O’Neill and Henry James, a Nobel laureate and a writer who should have been, neither noted for their “appeal and comprehensibility”. He clearly understood Buck’s shortcomings and all but says “Let’s not go there.”

In his book, Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography, Peter Conn uses Elizabeth Janeway’s New York Times review of Buck’s 1952 novel, The Hidden Flower, to bring in the feminist critique. I quote at length Conn’s quoting of the author of Man’s World, Women’s Place:

“Always widely read,” Janeway wrote, “and at one time the object of critical study, Pearl Buck is…relegated today to some amorphous anteroom of writing halfway – or more – between serious literary effort and best-sellerdom.” Criticism which placed high value on “the private struggle of a human mind with its interior world,” had no tolerance for Pearl, who dealt in busy plots and created characters that behaved like types. Even more damaging, Pearl’s “bias toward morality and toward a belief in order and in generosity,” made her seem merely naive in the eyes of what Janeway called the “intellectual critics,” who mistrusted love and preferred squalor to transcendence.

Janeway’s tone is sympathetic, but defensive and slightly baffled – Although she wants Pearl’s work to be taken more seriously, she isn’t quite sure how to make the case. In the end, she resorts to a rudimentary feminism, identifying Pearl’s importance with her female redership: “[I]t is too bad that Miss Buck’s audience is, par excellence, the audience that is ignored by contemporary critics of writing[:] the American middle-class woman who reads novels.” (p. 329).

So, if Pearl Buck’s reputation has fluttered downward from literary icon to one of the names most frequently raised against the Nobel and its process of selection, the fault, according to her arbiters, lies not with her frequently leaden pen and the hassle-free moral universe her character’s inhabit, but with those who value their opposites: facetted writing serving moral complexity. Their arguments take fertile points of inquiry, such as the strong appeal she had for middle-class women, and turn them into smoke bombs, obscuring the issue of her shortcomings and making it all about the anti-feminist elitism of her critics. The charge is not only unfounded but wrong-headed that someone who prefers, say, the high-wire act of The Adventures of Augie March, or the suspiration of time and meaning’s elusivity evoked by the very language of To the Lighthouse, ipso facto “mistrusts love and prefers squalor to transcendence,” and are therefore ill-dispossed to give Buck a fair reading.

Better, wouldn’t it be, to disentangle the issues, make separate files, as it were. In one file we place her rich biography – daughter of Presbyterian missionaries in a Chinese backwater, growing up speaking Mandarin before speaking English, founder of the first international inter-racial adoption agency, her ins and outs with the Chinese government, her difficult relationships with various men. In a separate pile we place her singular role as mouthpiece of the East to the West, the first to really define China for American and European readers. In a third file we address Janeway’s fascinating and somewhat touchy claim that she was primarily a “woman’s writer.” (How fun it would be to make about ten sub-files out of that one, one of which would be her emergence on the roster of America’s most remarkable and influential women.) In a fourth, we put the unavoidable fact that her prolific output is highly uneven, that her writing is clearly not that of a first-rank literary artist, and an investigation into why this is so by, yes Ms. Rabb, looking at the texts themselves.

Better, wouldn’t it be, to disentangle the issues, make separate files, as it were. In one file we place her rich biography – daughter of Presbyterian missionaries in a Chinese backwater, growing up speaking Mandarin before speaking English, founder of the first international inter-racial adoption agency, her ins and outs with the Chinese government, her difficult relationships with various men. In a separate pile we place her singular role as mouthpiece of the East to the West, the first to really define China for American and European readers. In a third file we address Janeway’s fascinating and somewhat touchy claim that she was primarily a “woman’s writer.” (How fun it would be to make about ten sub-files out of that one, one of which would be her emergence on the roster of America’s most remarkable and influential women.) In a fourth, we put the unavoidable fact that her prolific output is highly uneven, that her writing is clearly not that of a first-rank literary artist, and an investigation into why this is so by, yes Ms. Rabb, looking at the texts themselves.

When we step beyond the barracks of both her defenders and detractors, she all at once ceases to be a two-dimensional figure, a commodity useful to various agendas, and emerges as a fascinating writer, worth investigating on her own terms. The only question remaining is one to be answered by individual readers: Does her cultural and historical moment provide sufficient reason to spend time with her books, or is life too short to read her at the risk of missing Chekhov, or Proust?