Happy 100th to The Lord of the Fly in the Ointment, Sir William Golding

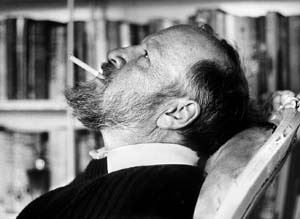

At some point during a book signing in Stockholm on the Tuesday following the Nobel award ceremony the newly laureled William Golding had to use the “loo”. Over five hundred people had queued up to meet the famous author, whose pessimistic view of human nature had, in spite of itself, yielded more than a half-dozen novels. Perhaps the wait was too much for one of his admirers who seized the occasion of Golding’s attendance to physical imperative, followed him into said loo, and requested his autograph. “A first, I think,” Golding said later. It is, of course, unverifiable whether the solicitation came before or after the business at hand had been completed.

A few days earlier, as part of the pomp and circumstance surrounding the awards, he had been presented to Carl XVI Gustaf. The King, a furrow-browed young man in spectacles, shook his hand and said, “It is a great pleasure to meet you Mr. Golding. I had to do Lord of the Flies at school.” Which sounds a bit like Royal for “Thanks for nothing you pedantic English turd.”

Both moments are commensurate with a certain lack of gravitas that seems to have attended Golding from the first announcement of his Nobel Prize, and which persists, in some measure, to this day, eighteen years after his death. I challenge anyone to consider his memory without a sympathetic wince: Here was a man who had spent his life working hard, often with troubled heart and drink-flamed nose, at being a serious novelist, only to have his efforts rewarded by being just a little better remembered for having written Lord of the Flies than for having been the first, and so far only, laureate in the hundred and ten year history of the prize to incite public dissent among the members of the Nobel committee. In a now legendary breech of protocol following the announcement, Swedish poet, Artur Lundkvist pronounced Golding “a small British phenomenon of no importance.” Then, backpedaling, but only slightly, which may have been worse than not backpedaling at all, he said, “I simply didn’t consider Golding to possess the international weight needed to win the prize, but that doesn’t mean I am against him. He is a good author.”

More public disparagement followed. Paul Gray, writing for Time Magazine, seemed particularly irked. To him, Golding was “a comfortable Englishman with no extreme political opinions,” whose work was of interest mainly to adolescents. How, he wondered, could the committee have chosen him over Gordimer, Grass, or Greene (all equally suitable “G” names)? It was enough, he thought, to “give pause to even the staunchest defenders of the Nobel experiment.” One must search, in fact, to find anyone, apart from Golding himself and a few notable supporters, Doris Lessing, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and John Fowles among them, who was actually glad of his award. The choice, if left to the British, would, it seems, have been either Graham Greene or Anthony Burgess. Lundkvist himself was an admirer of Burgess. “He is of far greater worth than Golding and is much more controversial.”

Golding put on a good face, as any discomfited “comfortable Englishman” would. To Michael Davie of the Observer, he said “That panel chose me. Another panel would have chosen someone else. So I am not in the least distressed by a dissentient.” As you say, William. But it had to hurt, especially all the invocations of his old rival Anthony Burgess whose book Earthly Powers had, just four years earlier missed catching the Booker Prize, scored instead by Golding’s Rites of Passage. Burgess took his revenge the year after Golding’s Nobel in a review of The Paper Men, which most agree is a thin book in more ways than width. He dressed his disdain in a coat of shining irony: The novel’s dust jacket had it that the Nobel Prize had been “the final recognition of Golding’s genius”, a “confirmation of his unique greatness”, to which Burgess responded, “It would seem to me that, with right British modesty, Golding has deliberately produced a post-award novel that gives the lie to the great claim. He is a humble man, and The Paper Men is a gesture of humility.”

All this fun at Golding’s expense could be chalked up to the perils, too common among writers and their keepers, of dining solely on ego salad. Lundkvist, for example, had been used to dominating the Nobel committee. He and his cohort, Anders Osterling, had been largely responsible for the selection of many of the more floridly obscure laureates of the post-War years. But Osterling had died the year before, at the age of 96, and Lundkvist, 77, felt the sapping of his clout. He went so far as to claim that the other committee members had “carried out a coup”, excluding him from the second round of voting. Now all comes clear. Lundkvist was feeling impotent and, like a character out of Philip Roth, made a scene about it. Problem solved. Give the old coot a Viagra to play with and leave Golding’s reputation in tact. Of course, there is the problem of his first published novel, the famous Lord of the Flies…

Just the other day I was telling a friend who does deep message that I was working on a post about William Golding. “Did he win for Lord of the Flies?” she asked, her elbows gouging my rhomboids. “The Nobel is generally given for a body of work,” I explained, groaning in pain. To which she replied, leaning hard near my left scapula, “I didn’t even know he wrote anything else.” “Ow!” And this is where it stays for most people. That monstrous brood of pre-adolescent English Hitlers, worshiping their skewered pig head and doing each other in on the set of Robinson Caruso has usurped what little energy the average reader has for giving Golding any attention at all. It is a work hogtied, so to speak, by allegory, unable to breath lest it awaken even a wraith of free will among any of its so-called characters. Even its few – very few – critical admirers concede that it lacks the subtlety he would learn to employ in his subsequent novels. Golding himself acknowledged its triteness. If this is the only book for which he is generally known, then doubts about his merit, whether ultimately sustainable, have a right to a hearing.

So then, explain The Times of London‘s 2008 published ranking of the fifty greatest British writers since 1945. Golding places third, just below George Orwell, just above Ted Hughes. A list, in itself, is a dumb beast, useless for determining the actual worth of anything. But, as with the Nobel roster, such a list can be suggestive: Clearly, there are those, and not a few, who continue to hold Golding in high regard.

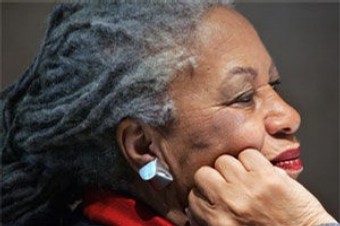

Sir William Golding, 1911-1993 In advance of William Golding’s centenary, I have spent the last few weeks reading his novels, trying to determine for myself if he is worth anyone’s bother. So far I have read The Spire, Darkness Visible, and Lord of the Flies. Yesterday I began Pincher Martin. After completing this one, if I have not burned out on Golding, I will read The Inheritors. I’ll be posting my impressions of each of these novels in upcoming weeks (though probably not until after next month’s Nobel announcement.). For now, I must confess that, with three novels down and a fourth begun, I still don’t know quite what to make of him. Clearly he is a better, more adult, more complex novelist than snippy Paul Gray would have it. He may even, on occasion, dance with greatness. Or at least wave at it. Nobel Prize material? Let’s wait on that one. In any case, reading him is giving me surprising, if mixed, pleasure.

I invite any of you who have read Golding, taught him, (met him?) even if it was a long time ago, to share your impressions. I would love to know what you think, what you feel are his best books, his virtues as a writer, his liabilities.

And now, to the shade of Sir William Golding: Today is September 19th, 2011. Happy 100th to you. May the memory of you and your work fare well.