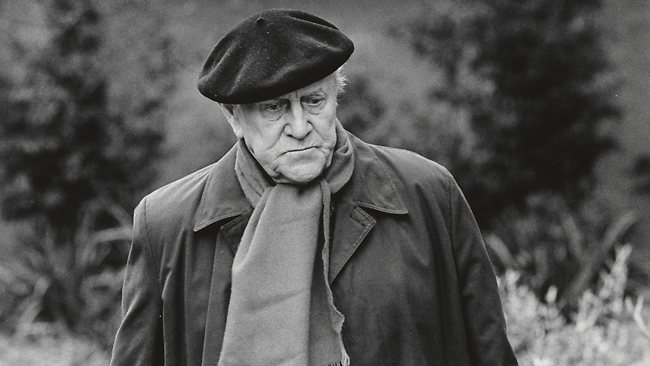

The time has come to speak of Patrick White, whose centenary on May 28th, is fast upon us. I will try to keep this post fairly short because I am currently in such a snit of idolatry that I won’t have anything especially coherent to say. I will simply put forth that, for me, Patrick White ranks along side Henry James, D. H. Lawrence, Joseph Conrad, Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, James Joyce, and Saul Bellow as one of the greatest novelists to write in English in the twentieth century. Hyperbole? You decide:

The woman winding wool held all this enclosed in her face, which had begun to look sunken. It was late, of course, late for the kind of lives they led. Sometimes the wool caught in the cracks of the woman’s coarse hands. She was without mystery now. She was moving round the winding chairs on flat feet, for she had taken off her shoes for comfort, and her breasts were rather large inside her plain blouse. Self-pity and a feeling of exhaustion made her tell herself her husband was avoiding her, whereas he was probably just waiting for a storm. This would break soon, freeing them from their bodies. But the woman did not think of this. She continued to be obsessed by the hot night, and insects that were filling the porcelain shade of the lamp, and the eyes of her husband, that were at best kind, at worst cold, but always closed to her. If she could have held his head in her hands and looked into the skull at his secret life, whatever it was, then, she felt, she might have been placated. But as the possibility was so remote, she gave such a twist to the wool that she broke the strand.

—The Tree of Man

Here is the Whiteian sublime. The physicality he evokes signifies without strain: note her too large breasts, elected from, we gather, a panoply of attributes waxing too large in her plain life. And how about that biblical ninth sentence, gathering into her obsessions the hot night, insects filling the porcelain lamp shade, the eyes of her husband, and finally something vast and forsaken at her core. Of course, we realize upon reaching the end of this passage, which feels more like a perimeter than a terminus, how obvious, the strand of wool will break, lacking, as it does, the heart’s resilience. Whole chapters could be written plucking the riches from the limbs of this passage. And, in a fictional output comprised of some six thousand pages of such passages, this one is more or less garden variety, making the oeuvre of Patrick White one of the most valuable gardens in modern literature.

Which begs the question, why is no one reading him? Why am I practically the only one I know who has even heard of him (apart from those few of my friends who politely let me blather encomiums)? His oeuvre has received sufficient critical attention to persuade me that I am not alone in my admiration. But even those who speak highly of him tend to refer to him as “the most important figure in Australian letters,” or “the first to put Australia on the literary map.” Three cheers for post-White Aussie writers. But White himself is so much more than the down-underwriter of his country’s literary life. He is a world writer in every sense, and should be spoken of in the same terms we reserve for José Saramago, Thomas Mann, Philip Roth, Nadine Gordimer. Why isn’t he?

In my search for answers I’ve been reading his books like mad, reading criticism, trolling the internet, and talking with friends. A distillation of what I’ve found comes down to these four points:

1. Patrick White is a high modernist, making him unfashionable in a post-modern world. As far as I can tell, what this means is that he followed Joyce, Woolf, Pound, and their ilk, in the belief that the old assurances provided by religion, society, and political designations, could no longer bear the weight of modern life and thought. These writers saw a sharp division between literary art and more accessible, or popular, writing. Their books are frank about their difficulties. White has been criticized for the density of his “mannered” or “poetic” prose, his “clotted images”, and fragmented sentences. Naturally, this will limit his readership, but it cannot, on its own, account for his enduring obscurity. His writing is dense, but not daunting. Most of the best of Faulkner is much more difficult. We don’t call Samuel Beckett unfashionable just because no one writes like him now.

2. Patrick White is too pessimistic, too dark, and what he asks us to consider about human nature – ourselves included – is beyond the pale for most readers. I concede this may be so. Many readers have commented on the “shock of recognition” which assails them on nearly every page. But this laying bare, this “truth telling”, to use a rather hackneyed term, this “vivisection”, to use a Whiteian term, is solidly within the purview of the artist. Do serious readers really find the meanness of Nabokov so much more edifying? Does one turn to Eugene O’Neill for a little cheer-up? If White is too relentlessly grim, how, then, make sense of the ever-rising star of Cormac McCarthy, who throws a dense, gorgeous, ball of modernist prose at the violence at the heart of the void? (White’s biographer, David Marr, has said, perhaps too felicitously, that McCarthy could be “up before Media Watch on charges of plagiarism by spirit.) While we’re at it, why don’t we, for the sake of our constitutions, leave Shakespeare on his increasingly dusty shelf while we get a little spiritual r&r.

3. Patrick White was gay. This seems to be the pet gripe of educated gay men of a certain generation, who, to compensate for their admitted fragility in the world, draw strength from being “the only gay in the village.”

4. Patrick White was Australian, making him peripheral to the bossier entities of the literary world. This argument is, sadly, the most persuasive. It grieves me to think that literature may be subject to the same laws as cynical politics: if a country fails to find ascendance in the consciousness of a more established block, it could drop off the map altogether and the privileged parties would be none the wiser. Sam, my partner, has a different take. “There is just so much literature,” he says. His point being, if you are looking to expand your knowledge of even just the essential modern writers, would it occur to you to look to a country known mainly for kangaroos, English convicts, a rather flamboyant strain of machismo, the world’s largest Gay Pride parade, one famous piece of architecture, and an accent often invoked in comedy? Of course there is great writing coming out of that lonely desert of a continent, or at least the thin portion of it strung along its Eastern cost, but its not where most of us would go looking for it. All the same, I would think the fecund sub-genre of post-colonial literature would be happy to hold up Patrick White as one of its shining lights. Can it really come down the banality that Naipaul, Walcott, Gordimer, Coetzee, and Rushdie hale from politically sexier homelands? But then, how to account for Les Murray, widely considered one of the three or four greatest poets currently writing in English. He’s Australian.

None of these explanations finally compel. Factoring in the idea that depth and brilliance in a body of work ought to outweigh whatever might be put in the opposing balance – an apparently fanciful notion in which I persist – here is one further explanation:

5. Ignorance of Patrick White and his work has, quite simply, become a habit. A bad one, I might add.

As with racism, car crashes, and other absurdities, I find Patrick White’s obscurity hard to live with. My question – why is no one reading him? – is not rhetorical, but an honest plea for responses. Someone, please tell me.

Why is no one reading him? Maybe because Patrick White espouses standards of openness and integrity that either mystify or terrify his readers. Think of the magnificent Laura Trevelyan in “Voss”, the guileless Arthur Smith in “The Solid Mandala”, the fragile Lotte in “The Eye of the Storm”, the sainted Mrs Godbold in “Riders in the Chariot”, and insightful Theodora Goodman in “The Aunt’s Story”.

White is not so much pessimistic as incomparably idealistic.

Gladys. First of all, welcome, and thank you for your comment. I think you have touched on something critical in Mr. White’s work. Openness. Integrity. Idealism. Mention them and you’ll find people shuffling their feet in embarrassment. They will think you are either talking about a naïf or a bore. Patrick White was neither. In my reading, am just now entering the thicket of the “Jardin Exotique” section of THE AUNT’S STORY. Theodora Goodman is slipping, and it is clear from what has come before that it is because her openness, integrity, and idealism, occupy her core, leaving her quite unfit for the world she must navigate. She receives everything, unfiltered. Ironically, those around her find her singularly closed, but I think it is because she has no “halfway setting” which usually makes social commerce possible, and like one of those delicate anemones which withdraws and seals itself tight at the least provocation, she knows how best to shield her soul. I think this must have been White’s condition as well. He was known, a bit one-sidedly, for being an angry man. I suspect that, more, he was deeply sad.

What a pleasure to hear from someone who has read so much of Patrick White and for whom his work has clearly been memorable. If you are so inclined to respond again, I would love to know how you discovered him.

David. I enjoyed reading your keen assessment of the first half of Patrick White’s “The Aunt’s Story”. Memorable for me is:

[Now she took the gun. She took aim, and it was like aiming at her own red eye. She could feel the blood-beat at the other side of the membrane. And she fired. And it fell. It was an old broken umbrella tumbling off a shoulder.

“There,” laughed Theodora, “it is done.”]

I’ve read all Patrick White’s post-war novels, only failing to make sense of “The Tree of Man”. I began, several years ago, by reading “The Aunt’s Story” to my 11-year-old twin boys. Hours afterwards, I must confess, I resorted to reading the blurb to make sense of the ending, a temptation I’ve resisted ever since. And, as with all his novels, the ending is wonderful. I particularly loved the cohesiveness of “Voss” and “The Solid Mandala”, while finding “The Vivisector” too dark and grim for my taste.

In recent years I’ve focused on Ibsen, Dostoevsky, George Eliot and, particularly, Henry James.

Science tells us there are very few singularities in the universe. Patrick White is one. You very well may be another: the only parent ever to read Patrick White to her 11-year-olds. Lucky boys. Though I wonder if they thought so.

Interesting that THE TREE OF MAN eluded you. I have just read it, and must confess that it figures in my current idolatry. The way he parses Stan and Amy Parker’s spirits, their large internal worlds which fail ever to really connect, or even to be adequately expressed; his us of the vast Australian landscape as an externalization of the distances they must travel in all ways; and, always, that language. Soon, I hope, I will have a post up on that book and I’d love to hear if you think I’m off base.

I also think it is interesting that in your last comment, all but one of the characters you mentioned are women. Some have faulted White for misogyny. I personally don’t see it. His women are flawed. But so are his men. And, at least in the books I have read thus far, the women are arguably the more richly rendered.

Your reading is inspiring. After exhausting my capacity for bliss on Patrick White, I may turn to Henry James. I read THE AMBASSADORS years ago, and would say it was one of my great reading experiences.

Thank God or whatever astrogenetic presence there may be for your existence, David, and for keeping “alive” so many of my heroes. Your piece the day before yesterday on White was truly poignant, as my friends and I have asked for many, many years the same question you have, only we’ve also asked it regarding the likes of Hamilton Basso, Ellen Glasgow, Jocelyn Brooke, and Leon Bloy, Arnold Bennett, Dawn Powell, Georges Duhamel, Nelson Algren. Just to name a few. I love your reading list, and I’m adding your site to my blog. Thank you again for your work.

Hello Mark, and welcome. Thank you for your generous appreciation and the link on your own fascinating blog. You indicate that you too have been perplexed by White’s lack of a readership commensurate in size with his gifts, and, perhaps more intriguingly, that you have friends who feel the same way. Lucky you to know a community of White readers. Thank you, too, for your list of of other writers whose reputations are, inexplicably, lurking in the shadows. I know a few of their names – Ellen Glasgow, Dawn Powell (who I understand is magnificent) and Nelson Algren. The others I have you to thank for having heard of at all. Sadly, I have read none of them. Or, perhaps not sadly, for what you have provided is a reminder of all the treasures waiting to be discovered.

I look forward to exploring your blog more carefully and at length. You are a novelist, I see. The synopsis of your novel, THE LONG HABIT OF LIVING, is quite captivating. I hope it finds many grateful readers. And your blog’s pairing of your fondness for Orhan Pamuk and John Cowper Powys is so beguilingly unlikely that it makes every instance of brainy quirkiness in the universe feel less alone. Pamuk is one of my heroes as well. A GLASTONBURY ROMANCE was my great, lumbering, and entirely haunting reading project of last year. That book….hmmm…We’ll have to talk.

I am truly surprised that no one has stated the obvious: the reason Patrick White is not read is that his characters—while richly symbolic and clothed in the most beautiful verbal finery since that of Bowen or James—do not live. Oh, they live in discrete passages, much like the one you quote in your post. But taken as wholes, they amount to intriguing creations, in the literal sense of the word, as opposed to discoveries, as they should (and do) in the stories that continue to compel through the decades.

And if the characters don’t live, if they don’t get us on their side as people to root for, then we don’t care what happens to them. And if we don’t ultimately care about their stakes, then even the most fascinating occurrences won’t be enough to make us turn the page.

It sadly comes down to the mechanics of effective storytelling, which no novelist, no matter how renowned, is allowed to forget. At least, if (s)he wants to be read after the heady encomia of his/her heyday.

(Although enough cannot be said in praise of White’s descriptive powers, which are truly and consistently stunning, by the way. I appreciate the precision of your question, as no one is arguing that the man doesn’t know how to write. The question is why no one willingly wants to read what he has written, at least today.)

I should clarify my bona fides: I read widely and well, and I adore the profundity and eloquence of “highbrow” literature along with the sheer drama and energy of excellent popular fiction. In other words, I am the sort of reader who can champion “The Hunger Games” and “The House of Mirth” in the same breath. I say this only to emphasize that it is not the famed complexity of his work that turned me off—I love “mannered prose” and “clotted images.” (And actually, I picked “A Fringe of Leaves” off the shelf randomly, having never heard of Patrick White until that point, so I had no expectations going in.)

But whereas authors such as James or Wharton, also in love with the sonority of English, never forget to craft arresting characters within an arresting plot, White uses his immense linguistic gift to pen pages upon pages of environmental and physical description that don’t cohere around believable and/or likable people.

There is only so much poetry that most readers can stand if it’s not connected to real characters. Considering your second reason, I think that many readers don’t mind dark or pessimistic characters, but they must be real. On the other hand, if they’re depressing AND they ring false, then it’s doubly repellent.

And so, White seems to remain one of those authors we admire from afar, without actually desiring to take him down from our bookshelves. Here are two quotations from critical works that echo my feelings about White’s work quite well:

“The trouble with Mr. White, as with Montherlant, is, first, that his scenes and his phrases read like cutting someone else’s throat, not one’s own at all; and second, that his self-gratifying obsession with human illusions of feeling has become eerily independent of any understanding of human feelings…”

Christopher Ricks, “Gigantist,” in The New York Review of Books (reprinted with permission from The New York Review of Books; © 1974 by NYREV, Inc.), April 4, 1974, pp. 19-20.

“After all the fascinating descriptions and adroit aphorisms, White’s characters, while not quite types, are exceedingly thin of blood. The blood they lack is White’s own, and if they are less than human, it is because he seems less than humane. With perhaps the exception of Frau Lippman, the author shows no compassion for any of these people. He is a demiurge, looking down, pulling strings, unsmilingly.”

Robert Phillips, in Commonweal (reprinted by permission of Commonweal Publishing Co., Inc.), May 17, 1974, pp. 269-70.

Maybe because you have to be a truly sensitive person to recieve Patrick White´s messages to your unconscious? To me he is the most mesmerizing – as well as the most virtuous with the language – author of them all!! ( And I have read “The Books” = The Western Canon). No one like him – he is the best and shall NEVER be forgotten!

Åsa Andersson, Stockholm, Sweden